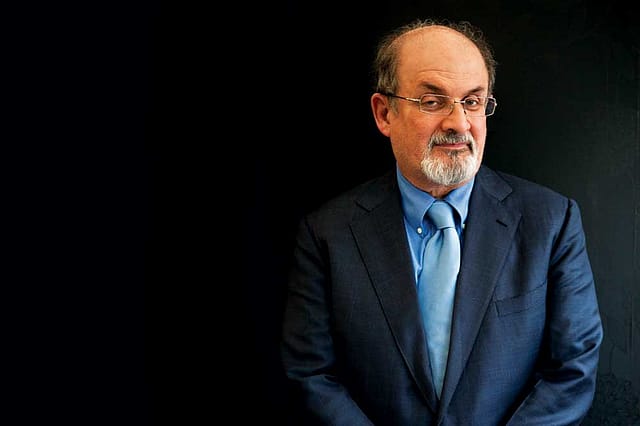

“That the world that you knew, and that in a way made you— that world vanishes. I don’t think I’m alone in that,” says Salman Rushdie

IT WAS UNDER very strange circumstances that I first met Salman Rushdie in the summer of 1988. I was seven years old. We were in London, my mother and I. She had just learned—I don't know how—I think it was from someone at the PMO who joked, "I always knew you were a terrorist"—that in Rushdie's new novel, his fourth, there was to be a Sikh woman terrorist called 'Tavleen' who blows up a plane. Tavleen was my mother. The name was unusual, a coinage of my

grandfather's. She had met Rushdie briefly in the early 1980s in Delhi with Sonny and Gita Mehta, but they were not friends. As far as she was concerned, she was the only Tavleen around, and the idea of this other terroristy Tavleen made her nervous.

It was a bad time in India. The Sikh militancy in Punjab was at its height. My mother, a journalist, had been covering it. She was inside the Golden Temple weeks before when the Indian army laid siege to it during Operation Black Thunder. Her reporting made her a target of the militancy, as well as suspicious in government eyes. There were death threats and inquiries. I had to stop taking the bus to school. The last thing she now needed was a fictional namesake who hijacks and blows up a plane. And so, that was why we went to meet Rushdie in the summer of 1988: to ask that he take my mother's name out of his book.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

We were too late. The celebrated author of Midnight's Children and Shame informed us that the book was already in print. What he would do—and did—was write her an apology. Producing a blue bound proof of The Satanic Verses, red devils quarreling on the cover, he wrote: 'For Tavleen, With apologies for the misuse of her name, Salman. 16.7.88.' Then, as we were leaving, he said: "But don't worry. It won't be you that will be in trouble; it will be me."

Six months later, Salman Rushdie was in hiding.

The memory of that meeting has returned to me many times over the years. Rushdie was the first writer I ever met—the god of my teenage years in India—and the threat he came to live under, in those final years of the Cold War, was the threat we would all soon be living under. It is that way with Rushdie: there is the work, dazzling and copious, but there is also the life, which has run like 'a purple thread' through our times. Indian independence; the Partition; the Emergency; demagogues on both sides of the border, and the rise of every species of fanaticism: they are part of the work; but they are also, in an almost freakish way, part of his life. History—and the pressures of the past—is his great theme; but he is also a plaything of history. It has used him in its story; it has made him seem like a character out of a Salman Rushdie novel, the creation of an imagination no less outlandish than his own. Writers normally sit at an oblique angle to the flow of events, quietly recording their passage. Not Rushdie. He has been swept up in the current, held aloft by the tide. He is a symbol of our times, forced forever to look in on himself, as if at another, and there must be something utterly weird about being Salman Rushdie.

That afternoon, in July 1988, I added to the general confusion by doing something extremely embarrassing. I was the estranged son of a Pakistani politician—also named Salman—who I had never met, and something about all the namesakes, fictional and real, swirling around, must have scrambled my seven-year old mind. Because—mortifying as it seems to me even now—I asked Salman Rushdie if he was not by any chance Salman, my father. My mother looked aghast; God knows what Rushdie must have made of this peculiar mother and son duo.

No, he politely replied, he was a different Salman.

The years rolled by. Eighteen, to be exact. The next time I set eyes on Rushdie I was a grown man. It was the summer of 2006. The Fatwa; the Cold War; the militancy in Punjab—it was all behind us. Rushdie had been out of hiding for almost five years, and was living in New York. I was living the louche life in London, paddling in the shallows of café society, while dreaming all the time of being a writer myself.

One night at Althorp, the seat of Earl Spencer, at a party given by a Russian oligarch for Mikhail Gorbachev, I caught a glimpse of Rushdie. I didn't have the courage to go up to him. The Scorpions were on stage, playing Wind of Change. Rushdie was dancing in a circle with Orlando Bloom and the erstwhile leader of the Soviet Union. The Cold War had never felt more truly over.

Fast forward five years. I'm back in Delhi, and now a writer myself. At the India Today Conclave, I'm asked to introduce Salman Rushdie. He had tried to come to India a few months before for the Jaipur Literature Festival; there had been protests; and both the festival and the Indian government, which has always let Rushdie down—India was the first country to ban The Satanic Verses—caved under pressure. This visit then was an act of defiance.

We were not the main act, but when word spread that Rushdie was to be there, the main act—Imran Khan, once a great fan of Rushdie's, pulled out. It was cowardice, but understandable. Pakistan—the 'insufficiently imagined' country of Rushdie's imagination—was on the boil again.

A few months before, my father, the man I had mistaken Rushdie for, and now Governor of Punjab, had been shot dead by his own bodyguard. He was defending a poor Christian woman accused of blasphemy, and Pakistan being Pakistan, he came himself to be a blasphemer, his killer a hero. Blasphemy! It was what they had accused Rushdie of all those years ago, and to meet him in Delhi, against the background of this new time, was to feel a circle of synchronicity was complete.

I offer you this looping narrative, because it is typical of the air of meta-fiction that surrounds Rushdie. He is forever bleeding off the page, and events in the outside world are forever seeping into his fiction. The new book, The Golden House, is no different. It runs smack into the age of Trump. It is set in the communal gardens that lie between Macdougal and Sullivan streets, deep in the Greenwich Village.

That is where this conversation occurs, on a hot July afternoon, swept with windy shadows. The house whose garden we are sitting in once belonged to Bob Dylan. It has, now for many years, belonged to our mutual friend the painter Francesco Clemente. He, along with his wife, Alba, are the dedicatees of Rushdie's new novel. As I'm awaiting Rushdie's arrival, with a cold six-pack of a Belgian IPA called Raging Bitch, Clemente texts to say he cannot be there. He has a pick-up, but will send his assistant Yana to take care of us. I had suggested to Rushdie that we meet in the evening, when it is cooler, and there are fire flies in the gardens; but the writer, who now arrives in a grey suit and a Panama hat, replied: "Evenings are no good for me next week I'm afraid. We'll have to sit in the shade, and imagine the fireflies…"

And that is what we do: there, in the shade of a magnolia draped in fairy lights, we sit down at a long wooden table on whose surface a single white orchid suffers silently. The sound of children screaming carries through the dead heat of the day. We talk of Love and Trump, of History and Women, of India and America, New York and Bombay.

Aatish Taseer: I'm convinced I just saw one of your characters go by in the garden. U Lnu Fnu, the Burmese diplomat in the book.

Salman Rushdie: [Laughter] I made him up. Frankie [Clemente] just texted me to say he's not going to be here.

He's got a pick up. Would you like a beer?

Not really. I'll just have some water. Is Yana here?

She is, I think. Or, on her way. So, what struck me most forcefully as I read your new book—what I found very moving—was a kind of euphoria about escaping the past, and what America could mean in this context. 'They would wipe the slate clean,' one character says, 'take on new identities, cross the world and be other than what they were. They would escape from the historical into the personal… to move beyond memory and roots and language and race into the land of the self-made self, which is another way of saying, America.' Have you known a euphoria akin to this yourself?

Not exactly in that way. But, of course, if you change countries, there's a part of yourself that you leave behind. And I mean, that's happened to me twice in my life.

India to England, then England to here?

Yes, so then the question you ask yourself, when that happens to you twice, is: what exactly has been left behind?

[Yana appears midway in a cool summery white dress.]

You know there's always loss, but hopefully there's also gain. I have thought a lot about both those things. Clearly my life would have been something else, if at the age of 21, I hadn't decided that I wanted to stay in England, and try to write.

And that was dominated by the desire to write, and the feeling that India would not be good for you in that regard…?

Yes, but it was also that my parents had recently—to my mind, mistakenly—moved to Karachi. And so, the family home in Bombay was not there anymore. I've always thought that if my parents had still been living in our house in Bombay that I would have gone back, and I would just have continued there.

Did you feel at that point that India was a place where you could make a go at being a writer?

It was difficult. Less difficult now, because there is more of a literary milieu than there used to be. That would have been difficult. But I felt deeply rooted in Bombay, and as far as I was concerned going to school [in England] had been an unhappy experience, going to university had been a much happier experience… but I thought of myself as from there. And had they not done this strange thing of moving so late… I mean nobody moved in 1960… the mid-sixties, you know… I think I would have just gone back there, and seen what I could do. But given the choice between Karachi and London, I felt much more at home in London than in Pakistan, where I'd never lived. But that clearly was a big fork in the road. And, in a way, Midnight's Children came out of that. Because after some time of living in the West, I became quite aware of this probability, or the possibility, of losing touch with where I come from, especially since my family was not living there anymore. And I didn't like that feeling, so writing that book was in a way an effort at reclaiming that past. And it meant a lot to me that the book was so well received there.

That first migration could have been quite simple. You could have had this experience of breaking, and beginning again, which many Indians did. But America was something else…?

Well, America was two things. It was first a youthful dream. I had come here as a kid. I came to America for the first time when I was maybe 25, 26 or something like that. And that was very different. New York of the 1970s, this area, was completely unlike what it is now, much more run down, and dirty… Anyway, I kind of fell in love with it, partly because it was very youthful. New York in those days, because it was so cheap, was around here full of young artists. So, you came here and you met young writers, young painters, young film makers, young musicians. I thought: this is kind of amazing. This is a city of young people trying to do creative work.

And then I came over the years, and I came to know it much better, and made many friends here. So, I told myself: one of these days… I want to just go and put myself there, and see what happens. I think it might be good for me. And when I actually did, towards the turn of the century, sort of around 1999, early 2000, when I finally did it, I truthfully didn't set myself any limits. I thought this could be a few months, or it could be the rest of my life. I'm just going to go and see. I didn't initially buy a place here. I only rented a place. I mean: it was complicated by falling in love, because that was also when I met Padma.

Padma was here?

She was actually in LA, mostly. But, for me, with children in London and so on, LA was not really an option. It was just too difficult to go back, and forth. And so, we sort of agreed that we would base ourselves in New York. Which was anyway what I wanted to do. I didn't really want to live in Los Angeles. So, I came. I didn't really know about the relationship, I didn't know about my own reaction to being here, etcetera, and quite rapidly I discovered that it felt like a very good fit. I just felt at ease here.

But also, on the abstract level of the idea of America… you kind of fell in love with that too, didn't you? I mean, you believed it? It has a hold on you.

Ya. But I've always thought the thing that has a hold on me is cities more than countries. I mean, I feel much more attached to Bombay than to India. And, in the same way, I felt a sense of belonging in London… And here…

You say that, but unlike certain writers, who write in very small ways about cities, you inhale countries. You deal in the grand format…

But the point of view is from the city. The point of view of America that one has from this city is very different than if we were, you know, sitting in Dallas… And there's plenty of America that I don't feel I would be at all at home in. But here, I did feel at home, and very quickly. Very quickly. That was what was interesting to me. I wasn't a stranger here. I knew a lot of people. So, it wasn't a cold entry. But I did quite unusually find myself feeling comfortable, feeling at home here at a very high speed, in a few months, and I thought: Oh. And I stayed, and then it became clearer to me that I would stay.

You spoke earlier about an anxiety about losing touch when you were in England, what about the anxiety of a writer whose entire subject is history, who adores history… What was it like to be in a place like America that is almost willfully ahistorical?

But you see, my whole training was as a historian, and I've never lost that way of looking at the world. In your final year in Cambridge, in a history degree, you do three special subjects. It's all you do. They offer you 75. And you just have to choose three, and that's all you do. And the three that I chose have in their own way ended up being very significant in my life: One was Indian history from 1857-1947, that was one. The second was: Muhammad, and the rise of Islam, the early caliphate. The third was the United States, or America, from 1776-1877, the end of reconstruction. I mean, these are three really quite extraordinary centuries. So, I was really quite deeply interested in American history from then, and have remained so. I actually do look at America as someone trained in American history.

Let me put the question to you in a different way. I don't necessarily mean the history of history books. I mean that, in a place like India, you can feel historical antagonism, people are living out certain historical situations, whereas here—I was actually going to read you this thing from Octavio Paz—where he says: 'The other great difference between the United States and India is in their attitudes to the past. I have already said that the United States was not founded on a common tradition, as has been the case elsewhere, but on the notion of creating a common future. For modern India, as it is for Mexico, the national project, the future to be realized, implies a critique of the past. In the United States, the past of each of its ethnic groups is a private matter; the country itself has no past. It was born with modernity; it is modernity.' This theme comes up in your book all the time…

Yes, it's the thing about a young country. Having come from a very old country, and then to quite an old country, and then to arrive in a young country, it's different. You know, a house in New York that's two hundred years old is really old. Whereas in London, everybody lives in houses that are two hundred years old. So even on that level your relationship with the past is different. And this is a very unsentimental town about the past. It tears down the past all the time. Every day you drive somewhere and you see a missing block. And what is interesting is that people immediately forget what was there. It is an immediate erasure of the past. Right now, if you go into midtown there's a block that is right next to Grand Central Station, which has disappeared, so you can actually see the side-ways view of Grand Central, which when the building goes up, we'll lose again. At this minute we can see the side of the building, but what was there till a few months ago, I have no idea! No idea. I have also suffered from the same kind of amnesia. This city tears itself down, and immediately people forget what was there.

This is very interesting to me. There's this feeling—and it runs right through this book, and the rest of your work as well—of release from the past, and then on the other side there's this Cassandra-like voice of caution that keeps reminding people of the dangers of that loss. In Midnight's Children, you talk about 'the clouds of amnesia'. That forgetting is on the one hand a very troublesome thing, but it's also a liberating thing…

Yes, as long as you know that it's both. One of the things I tried to do in this book [The Golden House]—it's related to your question about the ahistorical—is to do something, which is quite dangerous, which is to write up against the present moment. To write about the day before yesterday. It's very dangerous, of course. Because you can be wrong, you can be very rapidly outdated. There are all kinds of elephant traps about doing that.

It also seemed very exciting, and right about the kind of place I was writing about, just to try to engage with the absolute contemporary, and see if you could get some kind of handle on it, and capture it. I did it before, you know. One of the things that happened with Midnight's Children was that the later parts of Midnight's Children were being written as the events were taking place. I was writing about the Emergency while the Emergency was still happening. And I remember thinking that I didn't want the book to end like that, but I thought I can't end the Emergency in the novel if it hasn't ended in the world. So, when Mrs Gandhi called that election, and lost it, I felt kind of grateful to her. She gave me the end of the book! She allowed me to allow the book not to end in that moment. But I was really writing right up against it, you know… and there's actually a passage in Midnight's Children, in which Salim talks about this question of approaching the present, he talks about it using the metaphor of a movie screen, that the closer you get to the screen, the images break up, and I was very aware that that was what I was doing. And I'm doing it again.

That brings me to something I've been meaning to ask you. I feel that if intellectually-speaking we were to talk about Trump, or the political situation, you would regard it with a certain amount of dismay; but artistically, you've dealt with demagogues all your life. There's a line in The Golden House: 'Art is what it is and artists are thieves and whores but we know when the juices are flowing, when the unknown muse is whispering in our ear, talking fast, get this down, I'm only going to say it once…' There is a kind of artistic excitement in dealing with Trump, isn't there?

I mean, you know, monsters are interesting…[chuckles under his breath, then aloud.] There are all kinds of awful things one can say, for example, the arc of history that goes from Obama to the election of Trump is actually quite pleasing: to go from a moment of complete hope and optimism to its absolute negation. That's actually satisfying. I mean, I kind of guessed right; but I always also knew that if the other thing had happened [that is, had Hillary got elected], which would have been much more preferable to all of us, I would have had to shift the ending of the book around, and maybe it would have been less aesthetically pleasing… Somehow the thing that is very good for the book is very bad for us.

He likes you, doesn't he? Trump?

No. I don't know. He likes himself. But I've met him a couple of times. And he was very friendly. Terrifyingly. [Guffawing, and general laughter]

What did he say?

The most obvious demonstration of his affection was that—it was right about this time of year, when it was coming up to the US Tennis Open—and in that way that we've all become slightly too familiar with, he said, you know, that he had the best box—that his box was better than all the boxes. [more laughter]. And that if I—you know—wanted, I would be welcome to use his box at the US Open whenever I wanted…

Did you?

No, of course I didn't! I immediately thought this would be like a career-ending move.

Was it the first time that a future American President had offered you his box?

The only time! So, I've met him in passing two or three times, but I've never had a real conversation with him.

Well, we have this little background of history, and the past. So, when you see somebody like that [Trump], does he represent to you a politicised nostalgia for the past? Or is he quite an ahistorical creature? Where does he stand in relation to this idea of history?

Well, one of the things—you know, you were saying writing about demagogues before—one of the things I thought when I was writing Shame, which I thought again when I thought about Trump etc, was that sometimes you have very big historical events, which you can even describe as being tragic, but that the people are not of tragic stature, you know.

I remember you saying that. It seemed to you like a Shakespearean play with…

With clowns! And I remember thinking that about Zia and Bhutto and all that. What would happen if you would perform King Lear, with everybody in it, like, circus outfits. It would still be King Lear, but it would acquire some horrible black farcical quality. And that's sort of what I think about this. And that's why in a novel [The Golden House] which is otherwise completely realistic, I introduce this idea of comic-book figures to represent these powerful combatants. I mean, just to put it simply: the Trump and the Joker are both unusual playing cards. [laughter]. So, I thought: well if not this one, then that one. Many people have talked about Trump coming from a reality show background, and about the country being debased into a kind of reality show mentality, and I think there's a lot of truth in that. But I also think—in the way cartoons, whether Marvel or DC, have taken over the movies, things like that—I thought, in a way: here we are, three-dimensional, flesh and blood, realistic people, being ruled by cartoons.

But the politics of Pakistan became a kind of basket case, so that was in a sense anticipating the future, but what does it mean for a serious place [like America]… In the context of the book again, there's this very moving passage where you write: 'Maybe I was wrong about my country. Maybe a life lived in the bubble had made me believe things that were not so, or not enough so to carry the day… What would my story mean, my life, my work, the stories of Americans old and new, Mayflower families and Americans proudly sworn in just in time to share in the unmasking—the unmaking—of America…'

You were sworn in last year. I had just got my green card, and I remember we talked about it that summer, and you were being sworn in…

Yup! It's been something over a year now, just in time to vote in the election… [laughter]. Look, how well that went!

Obviously, the trouble lies with you, you keep bringing doom to these places…

Possibly! I mean, I don't regret it at all. You know I've been living here for 18 years or something, and I don't have any plans to not live here, so it's good to feel like I have full membership, you know. Because it frustrated me in the Obama elections that I was not able to vote. I just felt stupid to be in some way excluded. I mean, I've had the green card forever, but the green card of course doesn't let you vote. I just thought: take the extra step. And it was very strange: that it actually made an impact. On the day that I went downtown to get sworn in, and I was just in the yellow cab going home, through very familiar city streets, and looking out at them, and feeling differently. You know, feeling differently. Citizenship is a very powerful thing. And suddenly to not feel like a legal alien, but like a citizen.

But it's also something about the way this country does it. I mean, citizenship in Britain, you would have always known under the surface that you were kind of like…

Not. [Laughter] Yes, it is including.

You were presumably quite moved by it?

They're powerful words to say. In a way, like when you get married, those are powerful words to say. They're very simple words. Just as in a marriage ceremony, they're very simple words; but they have enormous force, because you're making a change in the nature of yourself.

And perhaps there was an acknowledgement that that change meant a tremendous amount to the people around you. That they were not just giving you a piece of paper, that they took it very seriously.

Exactly. And it is powerful, and I'm glad I did it, and it does feel a little different. A little different. I've said to friends of mine that it's as if after this lifetime of bouncing around the planet that the square peg finally finds a square hole. Click! Fit.

Because even with that Burmese diplomat in the novel there's this moment when he says, 'I'm never going home,' there's a point when you recognize that the journey stops here. Are you at that point?

Yes, yes I am. In the previous novel, there's this moment, when my gardener, you know, who's in love with his Djinn princess, where she tries to re-create him for the fantasy of the past, she sort of brings him back into old Bandra, and it upsets him. He says, 'Stop it. I don't want this.' That realization that the sense in which you can't go home again is: that it's not there to go home to. That the thing that felt like home to you has changed so much that going back there doesn't give you that feeling. And I think… Bombay, there's still little bits of what is now called South Bombay, where I grew up. Many of those little bits are still there, and they still have a kind of evocative nostalgic force, but they don't have more than a nostalgic force. They don't have the sense of telling me that this is where I belong. They just don't anymore.

There's this moment in the novel where a character says to Nero [the main protagonist], 'The city of my dreams is long gone. You yourself have built over it and around it and crushed the old under the new. In Bombay of your dreams everything was love and peace and secular thinking and no communalism, Hindu-Muslim bhaibhai… Such bullshit… Men are men and their gods and these things don't change and the hostility between their tribes also is always there.' And then there is this chilling bit: 'Just a question of what's on the surface and how far beneath is the hate.' Well, the hate has come right to the surface…

Well, yes. That's a global phenomenon. The rise of hate to the surface.

But wait, let's stay with India…

Yes. I mean, it's shocking to me… but you can be shocked, and not surprised. I don't think it's surprising. The way in which for many years—since the Emergency—politicians of all parties have used communal language in order to play this strange vote bank politics. They let that demon out of the bottle, and it doesn't go back in.

Is Modi an embodiment of that demon?

No. Not only him. I think, everybody. The thing that is more alarming than Modi is the popularity of Modi. The fact that he is very, very popular. And that means that it ain't just him.

Are you aware of a man called Yogi Adityanath?

Yes, I know a little bit about that now. The point is that there's craziness bursting out all over. There was a parallel article here that I read just a couple of days ago that said: stop asking yourself what's the matter with Trump; ask yourself what's the matter with us that we elected him. All these countries that I've been so deeply connected with—the post-Brexit Britain, the post-Modi India, and the post 2016 election America—it's all a question of what's the matter with us. It's too easy to put it all on the shoulders of one person.

new novel

Quichotte is

coming out in early

September 2019

But in Britain and America, there's a difference. The two sides have held. The pendulum could swing again. India has been completely remade, don't you think?

Yes, I think that's true. It's partly to do of course with the absolute Anschluss of the Congress party, the way there isn't an opposition, which gives the government a very free hand, and yes: they're embarking on a project of remodeling the nation, starting with text books… I haven't been there, so I'm a little reluctant to say too much. Because the last time I was there was before the Modi election. Four years I haven't been there. And that's been a conscious choice, because I had a really horrible time the last time I was there.

How so?

I got surrounded by so much security that it became almost impossible for me to move. And, you know, if you're in Bombay and you have a hundred men with machine guns going everywhere you go, you can't say to your friends, 'let's meet for a coffee,' and such and such, because you're arriving with all that. It became almost like house arrest. I mean, in a hotel suite… But it was very, very difficult to deal with. Because you know I've had periods in my life when I've had to succumb to some of that, and for a long time now I've not had to, and having got out of that trap, the idea of putting yourself back into the trap is anathema.

There was a strange moment. I was supposed to go to Calcutta to talk about the film [Midnight's Children] there, and then I was informed that the government in Calcutta had instructed the police to refuse to allow me to enter. And I was told that if I landed in Calcutta, I would be put on the next plane out. I thought: apart from anything else, it's incredibly insulting. And I thought, I don't need to be treated like this.

We've been talking history. What do you think is the deeper historical urge that is expressing itself in India right now?

Well, it's just that idea that the Hindutva people talk about all the time. Which is that in some way the Muslim arrival in India, and the many centuries of Muslim rule, and therefore, the spread of Muslim (rather than Islamic) culture, whether artistic, or architectural, or poetic, whatever—that, that is all somehow to be rejected. Because it was in some way inauthentic, and damaging of the—quote-unquote—'real India.'

And that the real India, which is Hindu India, must assert itself, and erase all that.

Can any good come from that? Because when I go there, and I see young people who are very proud, I find myself very susceptible—not necessarily to their politics—but to their feeling of hopefulness…

This is why I'm reluctant to say too much, because I haven't been there. And so, I don't know the answer. But what I do see has been unleashed is a kind of brute force, which is very worrying. And again, there are echoes everywhere. Like here, there are certain kinds of attacks that the President doesn't condemn.

Like what?

When it's an Islamist attack, he immediately condemns it, because it fits into his general agenda. But most killings in America are not carried out by Islamic radicals, they're carried out by crazy American people, and Christian fanatics, people with easy access to guns, who would not be able to do it if there was a different kind of gun law in this country. But, of course, he doesn't want to engage with any of that. He's very slow to criticize black people being killed by police officers, so there's a fairly obvious selection of where one should direct one's outrage.

Where are you on the level of fear and hysteria? I mean, there are some people who expect Brown Shirts to show up any day?

I'm not by nature hysterical in that way. I think there's really a long way to go before this is anything like a fascist country. I mean, we can have this conversation, and we don't have to worry who's listening… The one thing that I do think is that an attack on the freedom of the press, or the attack on the free press, is standard practice for would-be authoritarians.

The lügenpresse?

Yes, if you can demolish the public's confidence in the press, you make it much easier for yourself to sell them whatever bill of goods you want to sell them. And so, I think that attack on the fake-news, so called, that is dangerous. Because one of the things that people like me—when you were saying earlier about me buying into an idea of America—one of the things that people like me did buy into an idea of America—one of the things that people like me did buy into was the First Amendment. If there's one particular thing to point to in America that I really found impressive it's that. My thinking about the First Amendment really changed my view about ideas of free expression. Because, for example, if you grow up in England, where there is a Race Relations Act, it's illegal to make racist remarks, and you can be prosecuted, and sent to jail. In America, the First Amendment protects even that.

And in England [in relation to The Satanic Verses] there was a lot of that: Ah, but he went too far. Whereas here…

There wasn't that. And I really thought about which one of those ideas about free speech was better. I can defend the idea that saying horrible racist things is wrong, and that maybe you shouldn't be allowed to. But that question of drawing the line, about who draws the line, and where is it drawn. In the end, I just thought I want to know. If somebody in America believes in the ideas of the Ku Klux Klan, I want to know who those people are. I'd sooner know where the enemy is than have it all under the carpet, and behind locked doors. So, I came around to thinking that this extreme protection afforded by the First Amendment, which exceeds what is protected in England, or France—and certainly much more than India—I felt that that was closer to what I thought.

Have you worried about your place as a writer in America, [or for America], even just how to write about America? Do you worry that America might not know what to do with someone like you?

No, no. I'm too long in the tooth. At this point, I just say what the hell I think, and people can make of it what they like. There are people who seem to willfully misunderstand what I think. I can remember, to name only one person, very unpleasant personal attacks on me from Pankaj Mishra, for example, to my mind completely misrepresenting my politics, and my way of thinking about the world. But that's ok. I can argue back. But on the whole…

Well, since you brought him up, is there a certain kind of Left that is guilty of the things that it's being accused of? There's very nice discussion of transgendered identity in this book, and of identity in general, and the question of whether identity is a choice at all; or rather, as you say, a discovery…

Well, first of all, the question of identity is at the centre of the book. But what we mean when we talk about that is different. Here, the identity question is most often expressed in terms of gender identity, and of sexual politics. Whereas in India, for instance, it is much more in terms of religious identity, and communal politics. So, identity shifts. In England, the identity question had much more to do with whether England wanted to be part of Europe. So, the subject of identity is very heated these days, but the location of it varies in different places. I'm kind of amazed that there isn't a Museum of Identity that I made up in the book. And I suspect there will be…

Are there excesses of the Left that worry you…

Yes. I think those Left-Right terms are beginning to matter less to me; but I do think it is easier to see the excesses of the Right because they are so in your face. I mean, Marine Le Pen, or Steve Bannon, they are right there in your face, and you can see what the problem is.

But I'm not impressed by the unwillingness of the Left to call things by their true names. And this idea, which started with Obama here, of trying to somehow… for example, trying to separate the words Islam and terrorism, as if the people performing the terrorist attacks could not, ipso facto, be Muslims. That seemed to me like nonsense.

Someone who shouts Allah Hu Akbar before he blows himself up, and somebody who says that everything he does is done in the name of Islam—why should we not take that seriously? Now quite clearly it's an idea of Islam that many Muslims might reject, you know, but that doesn't mean it's not a kind of Islam. And to say that it must be considered to be Not-Islam in order to maintain the idea that Islam is a good thing, it just seems disingenuous. I know that one of the things that happened with me in India was that there were many people on the Left who were unwilling to be supportive of me…

Because you had offended Muslims?

Because I had offended Muslims. And I think that's still the case.

And, actually, when you look at the world—just casting one's eye out—yes there are moderate Muslims, but really the story is of the unraveling of that old Islam, the Islam you grew up with. The terrorists might be a tiny exception, but the change in the religion…

… is very real. It's very real, and it's partly fueled by enormous amounts of money for schools and priests, mullahs, to come and propagate this new Arabized, Salafi-Wahabi Islam.

So, here's a question: do you feel that what we're seeing in these countries—in the West, certainly in India—do you feel it's a reaction to what happened to Islam? Are we sort of recognising this threat among us, and remaking ourselves in the image of the threat?

There is some of that. I think certainly some of what elected Trump has to do with fear.

Because it's hard to imagine him in a world where Islamic terrorism didn't exist?

There is a fear factor, which he expertly manipulated. I think again in the Brexit vote there was a fear, but oddly it was a different fear. I mean, one of the things that has been unleashed in Britain is a hostility towards people with brown skins. Actually, they were more afraid of Polish immigrants than Muslim ones. But there was certainly xenophobia, and there's certainly xenophobia here, and here there is also always the continuing story of racism towards African-Americans, and I think all of that elected Trump. There was just a whole bunch of Americans who could not stand it that for eight years there was a black man in the White House.

And they wanted to hit back hard. I wanted to come back to this question of exile. There's another side to it that I found very interesting. There's almost a feeling of emasculation related to exile. At one point in the book it is said, 'maybe a woman's life gains its meaning through such metamorphoses… but for a man it is the opposite… The abandonment of the past makes a man meaningless… An exile is a hollow man trying to fill up with manhood once again… Such men are easy prey.'

Do you feel like you are easy prey? Has exile made you vulnerable to women?

No, because I don't feel like an exile. There's a difference between a migrant and an exile.

But you're kind of an exile…

I don't feel it. I mean, the bits of the world I can't go to, I don't care about. The bits of the world I do feel connected to, I can go to. As I say, there's a kind of problem that arose in India because of security, but that's a solvable problem. And I'm in the process of talking to people to solve it. No, it's not that kind of exile; it's not a physical exile. I remember reading… I don't know if this is true, or not, because this was only one news article… that the Indian Academy had refused to allow any of my work to be on the syllabus because apparently I was insufficiently Indian. That feels offensive, that feels more like being excluded from something…

But what about just the fact of your carrying around the broken pieces of different societies that don't exist anymore. I mean, I met you for the first time when I was seven years old; you were the first writer I ever met; and in the time since that meeting—in the course of some thirty years or so—every world that you have known, the kind of India you knew…

It's all breaking up. That's quite true, that's quite true. But I think that happens to many people if you have a longish life. That the world that you knew, and that in a way made you—that world vanishes. I don't think I'm alone in that. I think previous generations probably had that feeling too.

Yes, but there are people who have also known a feeling of wholeness…

I've always envied writers who have remained deeply rooted in one place all their lives, and just written from that knowledge. Like Faulkner. You live in this tiny corner of the world, and it's enough. You can make a lifetime of art out of your deep knowledge of that little place. I've always thought that would be nice.

But that hasn't been what happened to me. And so, you have to use what your life gives you. And yes, I do feel that the India I grew up in—and loved—is vanishing at high speed. That the England that I thought I knew turns out to be a different place. One of the things that all of the people who were on the other side of the Brexit campaign have to recognize is that the country isn't what we thought it was. And all this little England nostalgia behind Brexit—it's the same as Make America Great Again—comes out of that same nostalgia for a non-existent past. When was it that America was great?

On another point. You're seventy this year. In the years that you've been alive, we have seen the phenomena of the rise of America, of a country on the up. Do you feel that the years you have left in America will be a time of pessimism and decline?

This is a time of pessimism and decline; but, beneath that, there is another thing happening. Which also partly explains the Trump phenomenon: which is that the country is changing very dramatically. That White Americans are like a minority, and that Hispanic and other Americans are rapidly becoming a majority. And also, where the social attitudes of the next generation are much more progressive.

So, it's just a question of waiting for some old white people to die. Really?

Really, it is that. It's that Gramsci thing: the old refuses to die so the new cannot be born. It feels like a transition moment. There's old White America clinging on for dear life…

So, this seems to you much more like a last gasp, a death rattle…

I hope so. I hope so. Yes, it does feel like that… because it's so crazy. The things being clung on to are so before-the-flood, sort of ancient ideas… and one of the things that are puzzling about this country is that in the last few years, whenever there have been national surveys about the social attitudes of Americans, progressive attitudes have a very large majority. So, if you ask most Americans what they think about gay rights, or climate change, or gun laws, or immigration reform, on all these issues there are very large progressive majorities. The one exception is abortion, which is fifty-fifty. But, apart from birth control, there are progressive majorities on most social issues, and yet this country just elected the most regressive government that there's been in a century. And that's partly because nobody goes to vote.

Now you say that you love cities, but when you venture out of New York, do you feel that Nabokovian love for the great bosom of America…

In a way, yes I do. One of the things I've been thinking since I finished this book. You know you're always thinking: what next? The truth is I don't know what next, but I do know that I want to get out of the bubble. And, you know, if New York is this rather unusual place in America; I mean, I love it, but it's unusual, then I think maybe, you know, I have to get on the road. Like Humbert Humbert, and his motels… Sometimes you have to go and find the story.

You feel it's that kind of time?

Yes.

Now, we've talked about the past; we've talked about India and America; we've talked about Trump, I want now to talk about women and love…

Ya.

There's this thing that comes out of this moment of despair—it's in the book, too—which is almost a desire to live small, a desire to be wrapped up in someone, to have love as something that releases you from this situation…Where are you in respect to all this? You have kids elsewhere; you're older; you mentioned Padma earlier. Do these things prey on your mind…?

First of all, Padma, it's a long time ago. We've been divorced for more than ten years. And it feels like ancient history. And maybe not my wisest decision. But let it go. It doesn't matter. It is difficult being physically separated from my family. Not just both my sons, but my sister, and her daughters. That's not easy, but it's easier now that the boys are older. Because when Milan was little I felt the need to zoom back and forth a lot. Now they can do the zooming back and forth. They like the idea of having a place to stay in New York City. It kind of works out, but it's difficult. But there we are! It's just the way things are. As far as the rest of it is concerned, ya, everybody wants love. And I've been lucky and unlucky, and no doubt the next thing will let me know which one I am.

Is it different with age? Does that stuff make a difference? Or do you feel exactly as you did when you were 45?

Well, I feel the same, but it's quite clear to me that what people see is not the same. [Laughter] So it is different, ya. But you have to play the cards you're dealt. And it's alright. I'm not unhappy. I have a good life. [Pause] Don't ask me to tell you more because I'm not going to tell you. Not on the record, anyway…[Laughter] n

(This interview was conducted two years ago for the book Peerless Minds: A Celebration, edited by Pritish Nandy and Tapan Chaki, published by HarperCollins. The book is supported by a grant from Sunil Kanti Roy of the Peerless Group. All royalties from the book will go to the Ramakrishna Mission's Sister Nivedita School for Girls)