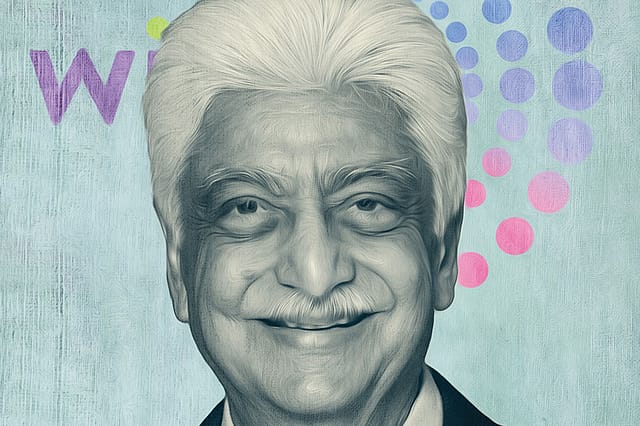

Azim Premji: ‘Being rich did not thrill me’

Are the rich different from you and me, as the narrator says in The Great Gatsby? Not if you meet AzimPremji, 72, India's second richest man and most famous philanthropist, with an estimated wealth of $20 billion. He studied in Stanford and is IT behemoth Wipro's long-time Chairman, a post from which he will step down on July 30th to pass the baton to his son Rishad. TIME magazine has twice ranked him among the world's 100 most influential people. In 2013, he signed The Giving Pledge to give away half his wealth. He was born in Mumbai in a Nizari Ismaili Shia Muslim family and he lives and works out of Bangalore. He is interviewed by Anil Dharker, journalist and former editor.

I met him first at a friend's wonderful sea-side villa at Alibag. We were there for the week-end, starting with a moonlit party on Friday night. Next morning at breakfast, our host casually said, "Azim Premji is here, and will join us for breakfast." The news was greeted with the exaggerated coolness we display to cloak our very real excitement.

He joined us and, surprise, surprise, was very much like us. What did we subconsciously expect, a crown and cloak? That's what the super-rich would have worn in the old days, and we would instantly know our place. Here, instead, we talked about the sea, the lack of pollution, which let us actually see stars at night, the freshness in the air. The usual sea-side chatter.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

At some point, talk turned to the trip back to Bombay. Everyone was going back on Monday in our host's private yacht. I needed to get back on Sunday. "I will take the morning catamaran," I said, "can I get dropped at the jetty?" Our host generously offered his yacht for the trip.

It turned out that Premji wanted to get back on Sunday too. "We can go to the jetty in my car," he said, "But will you drive it? It's Sunday, so I don't have a driver, and I hate driving. The driver will pick it up from the jetty." I made mental notes: firstly, one of the richest men in the world didn't own a yacht; secondly, he hates driving, but didn't call his driver. A third point hit me rather forcefully when I saw the car I was to drive. A Mercedes S series? A BMW 7? None of the above: it was a Maruti 1000. Even I had a Maruti Esteem!

On the way I asked whether he still travelled economy on domestic flights, as one had heard. "Oh yes," Azim Premji replied, "It's company policy." Who made the policy, I asked. He smiled, "I did." Yes, F Scott Fitzgerald was right: the rich are not like you and me.

But then, Azim Premji is not like any other rich person either. His frugal habits, bordering on self- denial, are perhaps matched only by Infosys' Narayana Murthy. Perhaps 'self-denial' is the wrong word; perhaps it's a question of paring down material goods and services to what is strictly essential. There's also a canny business sense at work here, which probably comes from Premji's family background: he comes from a Nizari Ismaili Shia Muslim family from Kutch where his father, Muhammed Hashim Premji, started manufacturing hydrogenated cooking oil with the brand name Sunflower Vanaspati. A by-product of the oil manufacture was the laundry soap 787. (Name chosen, but I am speculating, to be as close to the revered number 786?). The canny business sense works this way— if the Big Boss travels economy, how can anyone else in the company do anything different? Just imagine the kind of money Wipro must save every year by this one simple idea!

Wipro was initially Western India Vegetable Products Ltd, based at Amalmer, a small town in the Jalgaon district of Maharashtra. The Premji family was comfortably off, but not rich. One account tells us that Jinnah invited Premji senior to Pakistan at the time of Partition, but Premji said no. AzimPremji himself was born in Bombay (as it was then called) and went to St Mary's School, a boy's school, which has produced many illustrious alumni.

Premji's story of taking a small, fairly ordinary company and raising it through diversification and expansion to become one of India's biggest and most respected companies is extraordinary, but not unusual: other Indian entrepreneurs too have achieved remarkable success in one lifetime.

But what sets him entirely apart is his wish to give. And give, not just enough to salve a rich man's conscience, but give big. So big that his announcement that he would give away half his wealth was greeted by a collective intake of breath from Indian industrialists and businessmen. This happened when he became the very first Indian to sign the 'Giving Pledge' started by Bill Gates and Warren Buffet, and, for a while, remained the only Indian to do so. The announcement was made without any fuss: fuss, you think, is not in the Premji nature.

The Wipro campus where I meet him is quite a distance away from Bangalore's busy and overcrowded centre. The campus is spacious and green, and the buildings are unfussy (that word again!). They are not, you can clearly see, about to win any architectural prizes. But perhaps in their straightforward functionality, they are making the statement: we do not travel business class.

I am expected and there's someone to meet me at the gate and take me to a first floor conference room. When Azim Premji arrives, he apologises for being five minutes late. It's now 8.35 in the morning, so we are the only people in the building. Premji obviously likes to get his non-work work out of the way first thing. He has a shock of white hair, he is tall and fit, and speaks unhurriedly. At no time do I get the feeling that I am encroaching on his time. In speech, he uses the first person plural pronoun to refer to himself rather than the first person singular. But it's not the royal 'we' that's being used; the usage is more modest; it seems to say, whatever we are doing is a collective effort.

What surprises me later when I listen to the transcript of our conversation is how open he has been about the state of the nation, the feeling of minorities, or his opinion of a few fellow industrialists. There's no gag on me, no 'off the record' obligation, no injunction to not use portions of the recording. The onus is on me. I feel trusted, I feel responsible.

Is that why Wipro works?

From what I have read, you have a degree in electrical engineering from Stanford University, but your studies were interrupted because of your father's death.

That's right. I was only 21 when I was called back from Stanford in August 1966 to run Wipro. I did go back for one summer school, but I still had about eight or ten units left, which I finally convinced them to let me do by correspondence twenty years later. But they told me, please don't come for graduation because we don't want to set a precedent!

Twenty years is quite a gap!

I got an exemption from the technical courses—I couldn't recollect my math and thermodynamics after 20 years—so I just wrote on development studies.

Was there no course in IT then?

Electrical engineering came closest to IT, but there was no specialised course in Information Technology.

I remember FC Kohli telling me how JRD Tata asked him to be the first head of TCS. "But I don't know anything about computers!" Kohli told JRD. "No one knows about computers," JRD replied. "But you at least have a degree in electrical engineering."

When you came back from the US, did you first concentrate on building up on what your father had started?

We were primarily in commodities, in Vanaspati, which we sold to the wholesale market. We diversified into selling to retail with a brand and starting a distribution network. Then we went into toilet soap. We did a sensible thing in our diversification: we invested a lot in manufacturing plant machinery, which made it difficult to exit. Our first product launch was a failure, but because of our investment, we had to do a second launch of Santoor, which became a major success. We expanded that to toiletries.

How did Stanford help in all this?

Engineering really helps in analyzing issues. It kind of trains your mind.

What struck you as being special at Stanford?

There was a lot of latitude in course selection. I took a lot of courses in liberal arts, in the history of western civilisation, in the English language. I took a course in Shakespeare, an advanced course! This would never have been possible in India, here we get funneled into engineering, and that's that.

It was very mind-opening. I also played a great deal of tennis there and I joined, not a fraternity, but an Eating Club.

An Eating Club?

An Eating Club is where you just eat together, instead of eating in the cafeteria. I made good friends there, and the club organised a lot of programmes.

Does that mean that at heart, you are really a liberal arts person and you went into engineering because you were expected to?

That was the only way you could get foreign exchange those days. That was the rule: foreign exchange only for engineering. There was no choice really.

What would you have done if you had a choice?

I would have done Development Studies. If my father had not died in 1966, I would probably have got a job in the UN or World Bank for two or three years before deciding what to do.

Your business sense and feel for industry obviously came from your father. From where did your sense of philanthropy?

That came from my mother. She was a doctor, but she never practiced medicine. After she got married to my father, she started a children's orthopedic hospital at Haji Ali in Bombay. She started that for crippled children, for children affected by polio. She devoted her life completely, from the age of 27 right up to the age of 77.

We didn't have money at that point, so she had to scrounge around for it, get government support, then keep begging the government to disburse the sanctioned money. Government is notorious for that: they don't disburse. She worked six days a week, nine hours a day, and she had four children!

Quite a heroine then. Coming back to Wipro, what made you go into IT?

In the late 1970s IBM ran into conflict with the Industry Minister, George Fernandes. Fernandes insisted they should bring current technology into the country. They were dumping what had been withdrawn from the US seven or eight years earlier. Those were the machines they were selling in India, and, rightly, George Fernandes said if you want to continue with a majority status in India, you have to bring modern technology. They refused; so he forced them to dilute their shareholding to below 51 per cent. That made them switch off India and leave.

IBM had something like 80 per cent of market share, so their exit created a complete vacuum. We saw an opportunity there because we were anyway looking for a high-technology diversification. We went in, and there has been no looking back.

But you didn't have any expertise.

We put together expertise. We hired a lot from campus, brilliant people. We hired a lot from ISRO, from defence research. We put together an absolutely crack team. And we put a leader there who was not IT but was a good businessman. That was our unique differentiation: all the people who headed other IT companies were very technical, while we had a very strong orientation to build a business.

We started with hardware and after that sales, maintenance, and then diversified into IT services software.

Would it be true to say Indian software isn't very innovative, we haven't really made any breakthroughs?

We are doing a lot of innovation in services, but the innovation that gets noticed is in product software, which is oriented towards retailer requirements. For that you require an US presence, a very deep US presence to be able to build products.

On the other hand, in services software, cost arbitrage is the guiding principle of our success. Indian engineers are cheaper than foreign engineers, so we have automatic increase in profitability because of the cost arbitrage. Now the IBMs and the Accentures and the Capgeminis are replicating it: IBM has 300,000 people in India. Accenture has 200,000. Even a company as conservative as Capgemini has 100,000 plus people here, whom they use for global delivery, not just for the comparatively small Indian market.

Let's come back to philanthropy. It is said that people in the US are more philanthropic because of the tax structure there, but it's not the case here.

That's not true. Our tax structure for philanthropic donations is decent here. We don't have Estate Duty, whereas in the US that can take away 40 per cent of your money. I think Estate Duty will come here—it's just a matter of time. When it comes in, philanthropy will get a bit of stimulus in India.The situation now in India is such that the demands of the family are uppermost. People believe that their sons and daughters and wives and other relatives must come first, and must inherit most of their money.

What makes you different?

Being rich did not thrill me. And I strongly believe that those of us who are privileged to have wealth, should contribute significantly to try and create a better world for the millions who are far less privileged.

You were the first Indian to sign the 'Giving Pledge' started by Warren Buffet and Bill Gates, and I believe the third non-American to do so after Richard Branson and David Sainsbury. I saw the list of people who have signed the pledge. Hardly any Indians there.

There are a few.

Very few. And many of the Indian names are NRIs.

As I was saying, the Indian attitude is that the family comes first, and families became larger and larger with passing years. I am sharing an initiative for the past six years on public philanthropy where we meet once a year. We invite wealthy people who have a propensity to give. We have four workshops a year. We have a secretariat for this which I fund.

The objective is to get wealthy people to think more about philanthropy. We give them structured guidance on how they can build a philanthropic institution. The important thing is to institutionalise. We get Bill Gates to give a keynote every year. He is very committed to it. We don't force people to give—it's not part of Indian culture. If you force people, or even ask them to declare how much they are spending on philanthropy, they will back out. We have been moderately successful, but it's a long haul.

Do you see a change of attitude happening, however slowly?

Among the new generation of entrepreneurs, yes. The 35 or 40 year olds, they are more generous, more socially conscious. I think they will be a large source of philanthropic funding in future.

Does CSR—Corporate Social Responsibility—where large companies have to give 2 per cent of their profits, not help?

Too many people divert their companies' CSR funds into private philanthropy. We had advised government that they should put a ban on that. At Wipro, we don't give a single pie from our CSR fund into our foundation. They are completely separate. We have an annual budget of Rs 400 crore in Wipro CSR.

Is that also focussed on education?

Yes. On university education and engineering education. We focus on sustainability. Under 'Wipro Cares', which is funded 50 per cent by employees and 50 per cent by Wipro, we support crises like the tsunami in South India, earthquake in Gujarat and so on. But 70 to 80 per cent is dedicated to the area of education.

In a way, it's 'selfish' education. We work to upgrade the quality of teachers in engineering colleges we recruit from. That cuts short the process of induction. We have a four-year residential programme with BITS Pilani and the Manipal Institute. We give them a living allowance that is quite generous, so they can work and study at the same time. The students are free to continue to work with us or join another company. They are under no compulsion. But the vast majority continues with us.

As part of your own philanthropic efforts, you started the Azim Premji University. Have you introduced the kind of flexibility you found at Stanford?

Very much so. We are currently offering a Masters programme in Community Development and a Masters programme in Teaching, a Bachelors programme in Liberal Arts, which really prepares students for a Bachelors in Education, in Teaching. We have now 800 students, and an outstanding faculty, really outstanding. In the area of Liberal Arts, we rate in the top two or three in India.

What does your Community Development programme consist of?

You know, we recruit a lot from the smaller towns and villages of India. About 70 per cent of our students are on scholarships. For about 15 per cent of the scholarship students, we give in addition to room and board, a retainer so that their families can live. You see, we try to select people with experience, and when they are experienced, they are generally married and have children; so their families need that income. But as they are committed to development work, about 75 per cent of our students go into NGOs or teaching, even when they have many other job offers. That way, we have a very good track record.

You are saying that they go into developmental work out of choice, not compulsion.

I suppose we indoctrinate them well so that their main aim does not include making money. It's unique and we are very proud of that. In the two years with us, they'll be spending close to 16 weeks working in the field. We thus have a very large field presence in our education system. We now have 1200 people in the field, all full-time employees.

We give degrees in sustainability, in economics, in law—but again it's community law. So everything is slanted towards how they serve the community.

In the foundation, do you focus only on primary education?

We've got up to secondary now. But our main work is with school teaching. We work with the head teachers. We work with government functionaries. We work with state government authorities and the district training institutions. The aim is to upgrade the quality of teaching, the quality of supervision by the state administration and the quality of district training institutes. We also work with state governments in enhancing their curriculum of teaching. We try to influence government policy on education.

The impression one has that education in municipal and government schools is of very poor quality. Is this by and large true?

The key reason is the absence of good teachers. There are something like 15,000 teacher training colleges. I think 95 per cent of them are sham, complete shams. All these colleges came up because they got land at highly subsidized prices. You don't even have to attend any classes; you just get a degree!

There are stories of schools with no class rooms…

That's improved a lot now. There's a school within two kilometers of every village, and girls are getting enrolled as much as boys, but the quality of teaching is very poor. And then the girls get pulled out of school when the mother has a second child. Girls are the brightest students, but they have this terrible disadvantage.

How do you overcome that?

We establish creches in villages where all the children can be put together, and the mother can get to work. It's working reasonably well. Creches are not expensive you know: just a couple of rooms and a supervisor.

In a place like Orissa we work with NGOs who are involved in pre-school work. That's important because a student who comes from a very backward background, finds it very difficult to orient himself in the first standard. We fund governance programmes to upgrade the quality of governance at the village level. We work in the area of disabilities, we work in the area of street children and runaway children. We work in the area of women's rights.

All this is through NGOs?

All through NGOs. We act basically as a financing organization for NGOs. We employ only 65 people, whose thrust is on identifying the right NGOs in our areas of focus, evaluating their work, funding them and measuring them on their commitment during the funding period. It's working well.

But overall, your focus is on improving teachers. Correct?

Yes, we look at all elements: teaching methods, curriculum understanding, competencies in various subjects, the ability to learn. We show videos, we have inter-active sessions, there are case studies. They are willing to come for study even on Sundays.

Our experience is that 25 per cent of teachers that we get are excellent, 50 per cent are willing to change. That leaves about 25 per cent who are just callous. C-A-L-L-O-U-S. We don't put any effort into them because it's a waste of time. And they are protected by unions, which are very strong in education. We don't believe in taking the unions on.

Generally, we keep a very low profile. When credit has to be given, we give it to the state functionaries, to the politicians. In our experience, that's the way to succeed in working with the government.

You are not setting up too many schools yourself. Why is that?

We have a dozen schools. That number will go up to 25. They are really demonstration models. They set standards, which can be showcased to neighbouring district schools.

We don't need to spend money on infrastructure because it's already there. Governments have done a lot there. When the infrastructure is dilapidated, we get the community to chip in to upgrade it. People in the community are very generous: they provide labour, they give materials.

We get teachers who take pride in the school as does the head teacher and the administrative people. The allowances for cleaning, maintenance, electricity, they are not enough. But they still manage. The authorities have now also raised the standards for recruiting teachers. These new standards are very tough.

Another area where we focus on is District Teacher Training Institutes. There are 650 of these in the country. They are full-time with residential facilities. Unfortunately, all states have ignored them. So all the worst teachers and the troublesome ones are dumped there. Additionally, premises are in disrepair. We are now working very actively with the states to upgrade these institutes, to staff them with the right teachers and train them too. This has a multiplier effect because they will be training other teachers.

I want to get back to 'The Giving Pledge' where you committed to give away half your wealth.

By now 40 per cent already belongs to the foundation. That's quite large, it's $10 billion. So, the size of our endowment at today's value is Rs 65,000 crore. That's only next to the Tata group's in the country, and our disbursement rate is comparable to Tata's at Rs 500 crore a year.

Why is it that your personal shareholding in Wipro is so large? It's 73 per cent I believe.

When my father died, it was 50 per cent. I put every dividend I got into buying back shares. People said you are a fool, but if I don't have confidence in Wipro, who will? So I went up to 78 per cent. I thought I made a smart move. It's worth a lot.

Where will Wipro's future growth be?

Primarily in IT. We are geographically diversifying in a big way. We have now entered Latin America and Africa. We are putting a much higher thrust in Europe because we are at present not very well penetrated there. We are putting back a very high thrust in India. We see India as a growth market of respectable size, growing much faster than international markets.

And in which direction will your philanthropy grow?

Hopefully doing more of what we are doing now, and better. Imagine if our village and municipal schools teach well, what a difference that will make! Will we have made a difference to our nation? May be a small one, but even a small difference is a difference.