A God for Small Things

IN 1922, AN archaeological excavation was begun at the site of Ur, ancient capital of Mesopotamia (present day Iraq and Syria, 3800 BCE-450 BCE). The breathless global excitement at the findings at Ur were such that European royalty, and celebrities like Agatha Christie, flew to this remote Iraqi site in khaki suits and wide brimmed hats, beguiled by these mythical finds from the ancient past. One of the most fascinating finds was the tomb of an elite woman called Puabi, who had been buried wearing a great deal of exquisite, elaborate jewellery made from the most expensive materials known to the ancient world—locally sourced gold, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, and carnelian beads from a civilisation that had yet to be discovered.

But just because the world in 1922 didn't know about the civilisation the carnelian beads came from didn't mean the Mesopotamians from 5,000 years ago didn't either. To outsiders, and those across the seas, these people were called Meluhans and the land they came from, Meluha. So well established was contact between Mesopotamia and Meluha that a seal has been found belonging to a Mesopotamian whose job, as described on this seal, was "Meluhan translator". Today we know them as the people of the Indus Civilisation (3000 BCE-1900 BCE) and we are only just beginning to uncover some of their secrets.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Exactly 100 years after the excavations at Ur, discoveries at an Indus site in Rakhigarhi, Haryana, of a jewellery-making factory, appeared as a bubble in the frothy effervescence that is contemporary affairs in India, but it reminds us that Utopia, if it ever existed, may have been what the Indus Civilisation most evocatively reminds us of. Of the four great civilisations that co-existed during that distant age, only the Indus appears to lack all signs of warfare on any substantial scale. Egypt, Mesopotamia and China were founded on bloody wars and extravagant conquests. But in the Indus, there is no battle weaponry (helmet, armour, sword etc), no seals or imagery showing battle scenes, no large-scale slavery, no horses, and no substantial city fortifications. Those that exist are believed to have been used to defend and enable trade. As a corollary to this, there is also the almost complete invisibility of its rulers, and there are no monumental temples or royal palaces. As a result, the Indus Civilisation has been overshadowed by its admittedly more flamboyant contemporaries. It has nothing as astonishing as Mesopotamia's ziggurat or Egypt's endlessly photogenic pharaohs and pyramids, or China's remarkable, defensive Great Wall. What it had, instead, was pedestrian to the point of banality—trade.

Indeed, one of the sources of the Indus Civilisation's wealth and prestige comes from a humble material with a catastrophic origin. Sixty million years ago the subcontinent we now know as India was aflame with volcanic eruptions, and was in the fiery throes of birth as this land mass crashed away from the original supercontinent of Gondwana. The interaction of water and lava in this apocalyptic landscape, and then the precipitation of chemicals as the lava cooled, created a pale grey stone called chalcedony. Over millions of years, the hard chalcedony stone was exposed and brought down by river systems from the volcanic hills into the Ratanpura area in Gujarat where the Indus people mined them and perfected the technique of heating the chalcedony in the absence of oxygen to obtain the rich, red-brown hidden in the heart of the grey stone—carnelian. Beads were then made from the carnelian, polished and buffed to shining, crimson perfection. Some of the beads were decorated, producing the famous "etched carnelian" beads, and there were even long, cylindrical and barrel-shaped beads. There was such a craze for these carnelian beads in the Indus region itself that cheap imitation ones were produced, much like the Dior and Gucci imitation bags that swing on poles through the lanes of Sarojini Nagar Market in Delhi today.

If the locals were willing to make do with these cheap substitutes, it was because the very best beads, expensive and highly prized, were reserved for export. The Indus craftspeople bored holes through the beads using a technological process that was a closely guarded secret, befuddling researchers even today. For they were able to expertly bore through not only the round beads but even the cylindrical beads, three-six inches in length, using specialised drill bits made of a stone so hard that minerologists have yet to ascertain its origin. This rare "Ernestine" stone is just one of the many trade secrets that were known only to the Indus people, and which made them so highly valued and respected in the ancient world. For it was these long cylindrical carnelian beads that were found in the jewellery of the Mesopotamian noblewoman at Ur as Agatha Christie watched and dreamed of a novel called Murder in Mesopotamia. And it was the production of these high-value luxury items traded through sea-routes as far as Oman, Bahrain, Mesopotamia and then Egypt, which would have protected the Indus Civilisation from destructive attacks.

In fact, the perfected and small object is what the Indus people excelled at. Their beads and shells, ivory and seals, their finely calibrated small tools and instruments, their standardised weights, their figurines and their female figures, could all be held in the palm of the hand. The figurines they made overwhelmingly depict petite women, with a gamine figure proudly wearing an elaborate, individual hairstyle and equally distinctive ornaments. Almost no two figures are wearing the same sort of ornaments, seemingly reflecting a casual acceptance of endless individuality. And while the petite figure seems to have been the norm, there are round, chubby figurines too, companionably standing alongside the others, with no standardisation of an idealised female figure, which is the curse of modern notions of femininity. These figurines have not always got the love they deserve for they were first evaluated by European scholars, trained in the history of ancient Greece and Rome, for whom the small, dusty artifacts were underwhelming and disappointing. One such historian described them as "pop-eyed, bat-eared, belted and sometimes mini-skirted.. and of grotesque mien," an ungenerous description of these enigmatic ancestors.

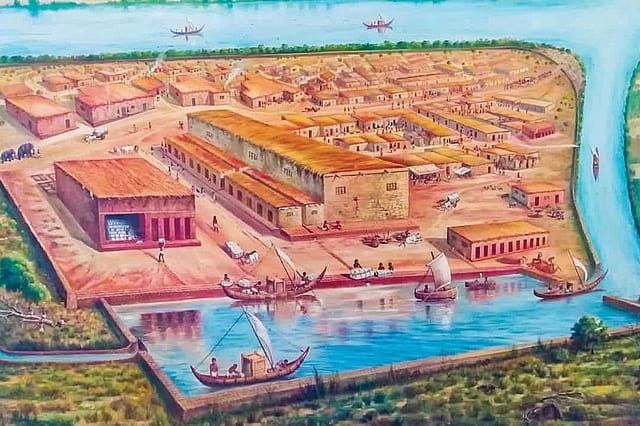

And since there appear to have been no great kings to eulogise or terrifying deities to placate or expensive wars to fund, the Indus people poured the wealth they earned through trade into urban centres that provided comfortable lives for their inhabitants. They built orderly and well-planned cities that integrated sewage disposal and drainage right from the inception of the city planning. Researchers have determined this from the fact that they were built on platform levels that created slight slopes, so that water could flow effectively through drains, avoiding the infamous monsoon "underpass flooding" that is the bane of every modern Indian city. And they could boast of a slogan that remains a challenge in India even for a 21st-century politician—A Toilet for Every Home!

And yet, for all their sophisticated urbanity the Indus people were also organically linked to the natural world. Their seals and imagery teem with animals, both real and imaginary. There are muscular bulls and delicate deer, and there are elephants, rhinos, pigs, monkeys, turtles and birds. There are chimaera creatures, half human half animal and there is the peepul tree, an object of veneration even so many thousands of years ago. There are even clay figures of domesticated dogs, and it is moving to imagine these long-ago ancestors finding comfort in the warm loyalty of these ancient companions to humans.

So, while the other ancient civilisations have their dreamy boy kings like Tutankhamun and their swashbuckling heroes like Gilgamesh, as our planet burns once more through another catastrophic phase, it is beguiling to remember that if showy extravagance has a great human cost, there once lived a people whose dreams, fragile and feral, were anchored in small and perfect things.