The Young and the Restless

Shows set in schools and colleges are edgier and greyer than ever before

Manik Sharma

Manik Sharma

Manik Sharma

Manik Sharma

|

19 Aug, 2023

|

19 Aug, 2023

/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Class2.jpg)

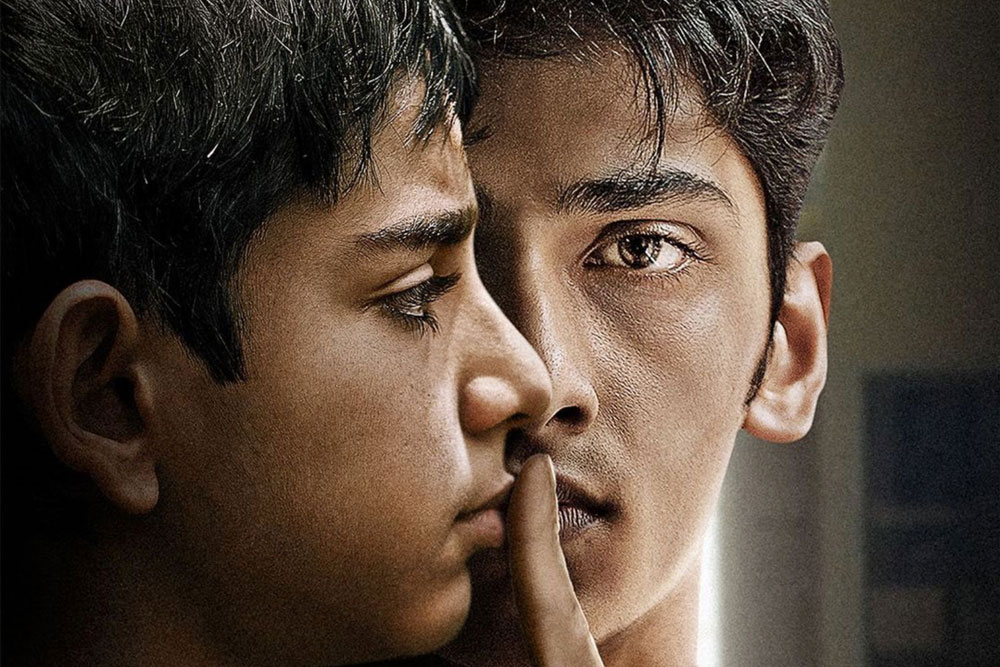

A still from Class

In a scene from Disney+Hostar’s School of Lies, Shakti, a young boy who has escaped from his boarding school to explore the woods, stares at a cracked egg being eaten by a chicken. “Does this chicken know it is eating its own child?” Shakti asks, grimly, of Chanchal, his young friend who is not from the boarding school. The scene is supported by a background score that suggests Shakti has inadvertently drawn out the show’s sociological origin. School of Lies is a bleak study of systematic abuse that infests a lineage of men, robbing them of their innocence. The system births a personality, while robbing it of its humanity. Shakti is the product of an absent parent, further imprisoned by toxic stewards at his school. It’s the kind of provocative space that young-adult stories in this country have rarely ventured into. But this is a brave new frontier, a place from where the young aren’t just viewed as carefree, jovial, anarchists, but also irreparable products of social and moral neglect.

Young-adult storytelling in Hindi cinema and entertainment isn’t a recent phenomenon. It’s edgy, voyeuristic overtures of late however, are. Curiously, the boarding school has featured as a destination for many of our young stories. There is probably something about the freedom of distance and the authority of structure that generates both conflict and self-realisation. It however also echoes privilege, a provision only a select few can afford; the kind that requires a mature lens, willing to acknowledge both entitlement and unchaste ways of the young. Streaming, increasingly, seems to be that stage the young have been waiting to tell their stories from.

Class set in an elite Delhi school examines the ripples from a cultural collision between the entitled and the underprivileged. Sex, drugs and violence punctuate a world where empathy comes at a humanitarian cost. Even at that young age, hatred and contempt can cloud your vision, the series argues

Ashim Ahluwalia directed Class (Netflix) exacts a muscular yet stylish view of young adult degradation. Set in an elite Delhi school this adaptation of the Spanish series Elite examines the ripples from a cultural collision between the entitled and the underprivileged. Sex, drugs and violence punctuate a world where empathy comes at a humanitarian cost. Even at that young age, hatred and contempt can cloud your vision, the series argues; harden a shell that takes more than a couplet or an inspirational poem to step out of. Class and caste are natural allies in this process of moral corruption. It’s a contemplative, edgy, perhaps even ugly image of the young.

TVF’s Kota Factory, a show that became a hit on YouTube before moving to streaming, looks at youthfulness through the comparatively modest lens of education. To a largely young country, a career, a job and the storied highs of India’s most premier institutes represent a summit. The climb, however, is filled with previously unstudied and under-analysed ups and downs. The show uses Kota’s many cliques, and engineering’s many peeves to paint a world where push and shove, make for awkward, despairing bedfellows.

Lionsgate Play’s Jugaadistan, and Prime Video’s Crash Course, offer an unflattering portrayal of the education system where the young are both the victims and the villains of a world they have learned to manipulate. Across these different stories, young men and women echo the moral and systemic complexities of a country that seeks control by nature and therefore provokes by design. Grammatically, these stories might suggest contrasting tones but their angst, their sexual and political receptiveness and their exploration of morality’s nefarious margins suggests a departure from the days when the young were hurriedly ushered down the path of righteousness, more so like an appeal or a lecture. These modern stories instead tackle vulnerability and moral greyness without dying them in the colours of virtue or vice. How we got here, however, is a long story worth tracing.

In Doordarshan’s Neev (1991), the young embody the casually competitive spirit of an unsettling age. In Jo Jeeta Wahi Sikander (1992), possibly our first mainstream portrayal of student life, class distinctions anchor the battle between good and perceptively bad. In Banegi Apni Baat (1993), a cast that also included the late Irrfan Khan, the young confront issues comparatively tricky in nature. From pre-marital sex to drugs, a certain contemporary streak that echoes the concerns of the era, begins to appear. It’s after all, the years of globalisation, the introduction of a global unknown into the bloodstream. The sites for these questions and resolutions continue to be urban.

It’s incredibly hard to find empirical references for young-adult stories in mainstream Hindi cinema. Bobby (1973) and Masoom (1984), have young characters, with a hint of pre-pubertal concerns, but their youth, their restlessness, hardly qualifies as the fulcrum of the story. “The problem is that in the US where teenage films are almost considered mainstream, there is a culture of discovering and creating stars. Here, everyone wants to play safe, and cast a known face as opposed to seeking a raw, young cast,” Nupur Asthana, director of the hit young-adult show Hip Hip Hurray (1998) says. Asthana was 26 years old when she approached producers with the idea for the show. Unexpectedly, she says, it was green-lit for a13-episode-long first season.

Asthana’s show was also a distillation of the impact globalisation had on our stories. A wave of NRI films queued at the theatres, marked by a noticeable change in the location of our episodic stories as well; a shift that had begun earlier. In Banegi Apni Baat, for example, there is a scene where a man describes to the waiter, just the kind of sandwich he likes, in great pompous detail. Indians at least in their imagination had started to reach out for things other than the usual dal and chawal. “With DeNobli, I wasn’t necessarily going for an aesthetic as such. But I did want to create a school that I would have loved going to. There was obviously an aspirational angle to creating a place of such liberal values, be it in the clothing or the culture,” Asthana says. She also claims that despite being on television, her stories were neither censored nor reprimanded for anything it might have touched upon from mental health to live-in relationships.

While cable television was prepared to go where mainstream cinema wouldn’t, there were at least signs of change. Nagesh Kukunoor’s Rockford (1999) may have come and gone, but it remains iconic as semi-edgy story about a boy’s induction into a boarding school. The late KK’s songs from the film are cultural heritage to anyone who grew up through the ’90s. By the time Star One’s Remix (2004) was launched, YA stories had again receded into the background, relinquishing preciously carved space. Barnali Ray Shukla, one of the first writers to be hired for the show, says, “YA had been neglected and erstwhile rebels were watching saas bahu shows with their grannies. People were actually coming together as a family to watch television. Not that Remix had reached where Tusli and Parvati Bhabhi had but then that would be like comparing apples and oranges.”

These stories might suggest contrasting tones but their angst, their sexual and political receptiveness and their exploration of morality’s nefarious margins suggests a departure from the days when the young were hurriedly ushered down the path of righteousness

Hindi cinema’s moment of clarity in the YA space arrived with Vikramaditya Motwane’s Udaan (2010), a landmark coming-of-age film that practically defied and denied the father figure for once. Udaan didn’t exactly send theatres into raptures but it remains a pivotal moment that the Hindi film industry has unfortunately failed to build upon. Fast forward to a decade later and streaming now appears to be that fertile place that has replaced television’s experimental, edgy days of yore. TVF’s Kota Factory, Liongsate’s Jugaadistaan, Netflix’s seductive Class and School of Lies have rewritten the rules of engagement for a country that though largely young, is still scouring for relatable stories to find itself in. Ishani Banerjee, co-creator of School of Lies says, “I don’t think the show is dark—it is a very human show. It is layered because it comes from a space of personal truths. All stories that do so tend to form an intense connection somewhere with some of the audiences. It’s a story of our times and space.”

Months before School of Lies released online, Netflix’s Class rippled through the internet with a stylish and raunchy portrayal of Delhi’s entitled school kids. Caste and class play a significant role here but it is at the end of the day, a series about young dysfunction, where young blood often boils over and above the tools of contemplation and empathy. Comparatively, Kota Factory engages with education and the country’s mass engineer-manufacturing industry, with empathy.

School of Lies, goes into diametrically different territory, illuminating systematic abuse, trauma and the degeneration of an elite schooling system we identify through its rigidity. These walls, however celebrated and historic, are scarred, the show tells us. Scars that walk around in tiny bodies waiting to be seen. It’s an arc that the show captures with Chanchal, a vagrant hill boy, who goes from being a mysterious shadow to the show’s beating, but indecipherable heart. “Chanchal was a shadow in the beginning, then he came alive because he gets ‘seen’ by Shakti. He gets accepted. That was a lovely character to build. You have to write them with your gut, with skin and blood and bones. There is no other way I know how to do what I do,” Banerjee says of her approach to writing the discomforting series.

Of the missing space for YA stories in the country, Banerjee believes it’s a case of a relatively young civilisation still feeling in the dark, for things it can touch, and those it must avoid out of the fear of discovery. “We are still finding our selves, trying to break shackles, assert ourselves culturally and fight both, an inferiority and superiority complex. This whole idea of individualism and identity has been tackled in the West for a very long time. They have been the colonisers, so their narratives are formed of their generational experiences. We are the colonised, divided by caste, and faith and what not. So, our narratives are unique,” she says.

Mainstream cinema is behind by at least a couple of decades in arriving at the point in the YA storytelling that streaming seems on the cusp of. It’s a case of both will and collective belief. “It’s a really hard industry to get projects green-lit in. A lot is about luck. I managed to get a YA show made when I knew nobody and knew nothing. Today, when I am somebody, it still hasn’t gotten easier,” Asthana, who has also directed a season of PrimeVideo’s popular Four More Shots Please, says. Popular directors like Karan Johar and Rakesh Omprakash Mehra, have come close to the YA space with youthful tangents in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, Student of the Year and Rang de Basanti, but these films conveniently externalise their conflicts, reducing the young to symbols of romantic restlessness. This new wave of storytelling, Banerjee believes, has to come from a place of earnestness so the stories aren’t slanderous and provocative just for the heck of it. “What we are creating is a reflection of our own selves. We have the privilege to do this now. With each passing year, we are evolving a little bit. But we are also at the risk of over exposure and explosion. We are at the risk of turning stories into mere ‘content’ for consumption and that’s a danger,” Banerjee adds.

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover-Shubman-Gill-1.jpg)

More Columns

Trump’s Disruption of World Trade Krishnan Srinivasan

Author Thomas Suárez presents peace framework for the Palestine-Israel crisis Ullekh NP

Shubhanshu Shukla Returns to Earth Open