The Alternative World of Rituparno Ghosh

The filmmaker who allowed himself to appear naked on the silver screen

"What is more important? The way we actually live our lives or the way we really want to?" asks reel life Ritu, the protagonist in Aar Ekti Premer Golpo (Just Another Love Story). Real life Ritu, Bengali arthouse cinema director/writer/actor, agent provocateur and my friend, probably echoed the same question in many an existential moment during his all too short life.

I remember his saying once in an interview that of all his characters, the one he felt closest to was Binodini, played by Aishwarya Rai in his adaptation of Chokher Bali (Dust in the Eyes). Binodini stood on a threshold of social transformation as she struggled for social acceptance as a widow after the British had legislated widow remarriage in the face of countrywide resistance. Rituparno felt a strong sense of identification with the tragic isolation of someone caught in the half-light of legitimacy.

It was this isolation perhaps that made him one of the most sensitive Indian directors of recent years. In a society with inequalities so deeply entrenched, he put across the struggle of being a human being—swallowed by desire, choked by experience, trapped by social expectations—with lyrical melancholy. And like all accomplished tragedians, he was the master of the dark poem, the kind of poetry that only comes through when bleakness is almost unbearable.

In the 21 years since he made his first film, Rituparno was part of over 24 films. He directed and wrote over 21 of them, and acted in his last three releases as the lead. His films have won over 18 National Awards, and have travelled widely across the international festival circuit. He is acknowledged as the central figure in the late 1990s' renaissance of Bengali Cinema that broke what was otherwise a bleak period. Best known for emotional dramas, his career spanned genres as diverse as children's films (Hirer Angti, 1992) and murder mysteries (Shubho Mahurat).

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

At a time when cinema was centered around the 'Hero', Ritu chose to make film after film about women. Unishe April and Titli, with Aparna Sen and Konkona Sen, both explored the tensions and intimacies of a mother-daughter relationship. Bariwali won Kirron Kher a Best Actress National Award for her portrayal of an ageing spinster in a decrepit house in a state of slow decay. Dahan explored the apathy and misogyny of society around victims of sexual assault.

Ritu was always willing to take risks. From incest to infidelity, he invested the hitherto sacrosanct middle-class Bengali family on screen with narratives that had been wiped off cinematically in the sanitised blaze of mainstream depictions. In Utsab, Dosar and Shob Choritro Kalponik, he explored complicated, damaged and often flawed human relations in a sensitive but unsentimental way.

Rituparno was willing to break cinematic norms as well. For example, Dosar (Companion), a tale of an unfaithful marriage in the afterlight of an accident, was shot completely in black-and-white. Shob Choritro Kalponik departs from linear narrative and descends into surrealism as a stunningly beautiful Bipasha Basu is interrupted in her infidelity by her poet husband's death, an event that leads her to re-interrogate her entire relationship with him.

Inspired by Bengal cultural icons Satyajit Ray and Tagore, Rituparno's films helped define the next generation of Bengal New Wave cinema. He paid tribute to Rabindranath Tagore by reinterpreting three classics: Chokher Bali (which won him the Locarno Best Film Award in 2003), Nauka Dubi (a period film) and his most recent release Chitrangada.

By the time I came to know him, Rituparno Ghosh was a star director and had earned the reputation of being something of a diva. His Hindi film Raincoat, featuring Aishwarya Rai and Ajay Devgn, had established him as one of the few to cross over from regional cinema to Bollywood. Other mainstream Hindi actors like Manisha Koirala and Bipasha Basu had also worked with him. He had hosted two celebrity chat shows, Ebong Rituparno and Rituparno and Co, in which he addressed his guests fondly as tui (an intimate 'you'). His most telling moment on TV was when he publicly scolded Mir, a well-known mimicry and stand-up artist. Mir had in the past used Ritu as material for his comic routine. Ritu shamed him on national television in that one show, asking him if he realised how prejudiced he was in poking fun at effeminate men.

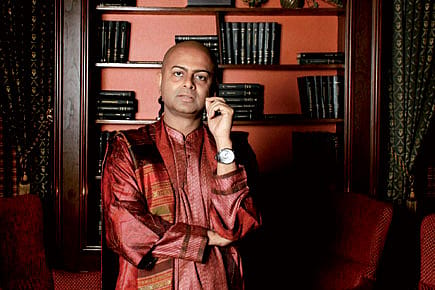

Ritu himself had always been effeminate, but he slowly claimed his queer self in public spaces. His flamboyant turbans, kohled eyes and flowing robes earned him notoriety and a grudging respect in Kolkata's art appreciation circles. It was his city, one that 'could neither ignore nor embrace him', in his own words.

I was curator at the I-View film festival in New York when we invited Aar Ekti Premer Golpo for a screening. I had been following Ritu's films for years and was already a fan. Yet, we were especially excited about this film. It was the first time Ritu was to act in a movie, and that too, in the role of an openly gay filmmaker. The film's director was Kaushik Ganguly, but it was Ritu's story. His involvement in every frame of the film was well known. Discussing pre-festival logistics with Ritu was difficult, to say the least. But all that became inconsequential the day we, the programming committee, saw the film. There was no one in the room who did not understand how momentous that film was in its representation of queer life. It felt as if his entire career had led up to the courage it took to make that one film.

Rituparno made Memories in March and Chitrangada after that. These dealt defiantly and unapologetically with the exile of homosexuality, with retribution and, finally, redemption. Each was an intense exhalation for queer audiences. In the deafening din of mainstream heteronormativity and the trite stereotypes that are often the only representation of a largely silent and invisibilised community, here was cinema that made them belong. There was desire, pain, complexity, beauty, isolation and finally poetry. In his specificity of representation, he created cinema that was universal.

Over the many late night conversations I had with him over time, even as we discussed such things as what he should wear on the red carpet, I came to understand what courage and conviction were. I realised how difficult it must have been for him in the current climate of commercial safety to ask producers to take risks on his films; to ask actors to stretch themselves and take that leap of faith with him; and to let his own self appear unveiled and so vulnerable on the silver screen. Every story of his was personal, no matter how fictional.

I wept when I heard he'd left.