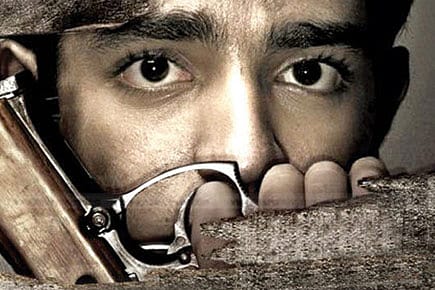

Sikandar

Into the valley of Kashmir rides another confused tale of lost childhood that offers no insight into real issues.

Into the valley of Kashmir rides another confused tale of lost childhood that offers no insight into real issues.

Piyush Jha's film had the possibility of becoming the real thing—a keyhole view to how we've made a mess of the subcontinent's most beautiful place—by foregrounding its children. But what we get is a hodgepodge of conflict-zone politics presented in the form of a thriller. And there isn't a reference to anything across the border. Warts and all, India is basically the good guy.

Sikandar tells the tale of schoolboy Sikandar Raza (Parzan Dastur), leading a childhood in picture-postcard Kashmir. Beset by fires of azaadi, the football-loving Sikandar, who's bullied by schoolmates, befriends Nasreen (Ayesha Kapoor), and chances upon a revolver. It begins as curiosity for the gun but turns into a manic love for a weapon of self-defence against his bullies.

The revolver belongs to a mean militant (Arunoday Singh) who comes looking for it, finds Dastur, develops a bond, and begins to train him for his first murder assignment. In the backdrop are vengeful army man Madhavan out to finish off all militants and local Kashmiri politician Sanjay Suri. The hunt for Dastur is a sprint that fast tracks him into losing his innocence, only for him to tellingly discover that he wasn't the first to lose his childhood this way.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Jha's film is patchy, even grating in its visualisation and especially its background music in the first half. (A combo of Sufiana and Gospel). At its best, the film captures the screams and silences of ice-cream mountains, mynah cawings, rivulet rhythms and dribbles. Dastur and Ayesha and their interactions are just above the amateurish. The latter, though, for her nunnish austerity, is sharply etched. But none of them become real people, as Jha doesn't bother investing any character with psychological power—until the ending crescendo.