Rambling Man

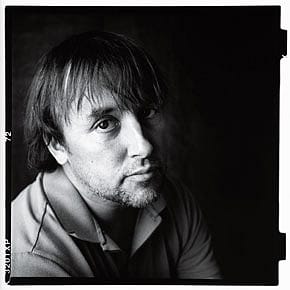

In the candid banter typical of his films, Richard Linklater talks about a career on the periphery of the Hollywood studio system

Is there an easy way to introduce Richard Linklater? An icon of American independent cinema, often credited with paving the way for the era of low-budget, light-comic, self-exploratory gen-X movies, Linklater's legacy as a writer-director is deep and varied, his films fiercely original and undeniably interesting. He has managed to forge an inspiring film career by living and operating at the periphery of the American film industry in the era of clone blockbusters, and is one of the few remaining high-profile filmmakers who work not for money, but for the love of cinema.

Before Midnight, the long-awaited third film in Linklater's utterly beautiful and romantic Before… series starring Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy, released across the world earlier this year, premiering in India at the recently- concluded Mumbai Film Festival. In his first ever interview with an Indian publication, over the phone from his home in Austin, Texas, the director of cult classics like Slacker, Dazed and Confused, Waking Life and School of Rock offers an insight into his mind and craft. And he's just as amiable and charming as every one of his films. Excerpts:

Q In the 18 years it's taken to complete the Before… trilogy, how has your idea of love personally changed?

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

A Now that I think of it, for Julie [Delpy], Ethan [Hawke] and I, making these films sort of introduced [to us] this subject of long term relationships and the definition of love or what love even means. That's become the subject of our lives, you know. I find myself reading a book on that or reading articles or statistical data on couples.

Movies are like that—when you are making a movie, you tend to feel that you are doing a Masters [degree in] whatever the situation is. Over two decades now, this subject [has] really made me follow notions of relationships of long term, and question how things change and how things remain the same.

I don't know if that's an answer, but it's definitely a subject in our lives and I'm always constantly thinking, 'Oh this could be good if we ever do another movie—this notion or piece of information'.

So we can look at it both emotionally and scientifically, and we have our own lives going on with our long term partners, and it's involved in there too.

Q In this time, how has the idea of love changed for Hollywood? Is 'romance' still relevant today?

A (laughs) I don't know. I mean, the first film, Before Sunrise, wouldn't happen today, or at least in the same way. It certainly wouldn't have the same result, like they wouldn't exchange numbers. I mean, they would get each other's emails or texts, you know. People communicate differently today. That film was a little old fashioned even then.

I don't think young people would approach love the same way [now], but I still think the core of that movie—two people meeting, that moment of attraction, of falling in love—that never goes away. That's relevant. That was relevant 500 years ago and will be relevant 500 years from now. Nothing's going to change in that area between people. There is something about that that is eternal, but the details of it change generation to generation.

But I can honestly say that Before Midnight covers an area that is not covered a whole lot in movies today, for obvious reasons. It's not about the beginning of a relationship, it's not about the end of a relationship. It's about when they are having their problems. It's kind of the middle area, which is not often used as subject matter for something in the romantic realm. It's not very commercial. You don't see a lot of compelling films made on this. Hollywood would never touch these films.

We have a low budget, and we make these independently, so we can do whatever we want and express things that don't need to fit into a Hollywood romantic comedy construct. We can make something that we feel is much more honest, but we know we don't have a huge audience for these movies. We just kind of figure our audience might appreciate some of the blunt honesty (laughs) of our characters in their situation.

Q I'm also asking about love in the time of the movie studio, because the Before… trilogy is one of the few movies where romance is real and uncontrived. How did you manage that?

A That's a compliment, thank you. I think it's just the approach. It's what you are going for, you know? What is real? I don't pretend any of it is actually real. I mean, they are not documentaries; they are actually scripted and rehearsed excessively, very well thought out, very constructed.

But the effect I am going for in the viewer's mind is [for them] to accept it as some kind of reality, to feel like it's real.

I don't know if people want to feel that way. I like going to movies often, going into someone's unreality. When you go into a Tim Burton film or a James Cameron film, you will enjoy being in their reality, [which] you know is not real but it's wonderful. I'm not asking people to be in some kind of parallel reality, but to relate to [a film] on a closer level.

That's what I love about the way people perceive movies. I kind of like that a film could be anything and mean something different to every one; it just has to be true to the story you're trying to tell. People just come along for the ride.

Q When Ethan Hawke, Julie Delpy and you got together to write Before Midnight, how did you find common ground for it, considering that you might all have been in different places emotionally after 18 years?

A I think we just incorporate our different moods, you know. Whatever changes in character or whatever vibe you get from this movie that's different from the last one probably reflects our changing mood, the atmosphere, the things we've all been through. I've tried to incorporate our personal reality into this film, into something that's real for Jesse and Celine.

I think Ethan, Julie and I trust each other artistically, so we don't have to work too hard to find common ground. I think we are all trying to be honest when we write something that means something to us. Julie not feeling good about something or being paranoid about something, you know, some of that might find its way into the movie. Or if Ethan is feeling creatively satisfied and has such ideas, then we'll work that in. So we're kind of basing the film on where we are at, to some degree. Our writing sessions were like comedic therapy (laughs). We'd sit around, laugh a lot, and just talk for hours and hours.

Q How would you say you have evolved as a writer and director in these 18 years?

A You know that's a good question, because I don't know if I have that much (chuckles). Stylistically my movies are still very similar—well, I do that on purpose—but I don't know if I've matured that much. With anything you do, you get a little more confident, you get a little more experienced. I guess that's all good, but I don't feel I have changed significantly. I think my concerns are pretty much very similar. What I'm getting at is that I'm always surprised I'm much more similar than different.

I would say the same about Jesse and Celine: it's not so much how they have changed; it's really more interesting how they have stayed the same. And to think of it, am I that different than I was at 24? I am more mature and more experienced, of course. Life has a way of doing that whether you like it or not. But the gist of my life, what I'm interested in, what I care about, artistically, it's still kind of similar.

Q You've mentioned that your films are semi-autobiographical. How many movies do you think you'll need to express all facets of yourself completely?

A (Laughs) Well that's really the question, isn't it? I don't know. I wonder if Ingmar Bergman [would say] at the end of his life… that he expressed himself completely in his movies. I don't know if that's even possible, if any filmmaker is totally satisfied. [Michelangelo] Antonioni, towards the end of his life I think, finally wrote a book [That Bowling Alley On The Tiber: Tales Of A Director] to say, 'Here's 30 movies I'll never make.' He had ideas, and a few pages about each of them. A book about unrealised movies—I could do that book now. I have 10-15 unrealised films (chuckles).

But to answer your question, you'd have to make, like, a hundred. Every film does say something. In every one, you are communicating something. But that's sort of the challenge artistically, isn't it? To try to express what you want to express. And some novelists or writers have perhaps spent thousands of pages trying to do that. I admire people though who kind of say, 'No, I've said all that I have to say,' and [then] quit writing, quit making movies, quit painting or quit making music. But I don't really believe it. I don't think you can retire from expressing yourself.

Q Do you write to discover something about yourself or do you already have philosophies you centre your films around?

A To be honest, I am always trying to discover something. I don't look forward to the day that I have some knowledge to impart. If I have something worth making, it's something I [either] have mixed feelings about or am trying to discover something about, or I'm not totally sure what I think about it, and that's why I think it makes it fertile ground to try to make a movie.

To make a movie about something, specifically, that I definitely have strong feelings about and then [to] convey them exactly—that's a lot less interesting, I think. Things you have strong opinions about find their way into the general tone and core of the movie anyway.

Films are truly much more about the exploration of your thought and lot of exploration is just the process of making a movie. And I'm inclined to think that everybody feels that way. I wonder if [Alfred] Hitchcock felt that way. Was he just physically manifesting what he had all planned out or was he discovering his deeper feelings about the subjects that he made [films about]? For example, in Vertigo. I don't think anyone just renders something they've just printed out, as much as they try.

Q Your movies are very dialogue heavy, and that goes against the conventional wisdom of cinema, except if you are, say, Woody Allen. Why is dialogue so important to you?

A I don't know. You're right; that is Film School 101. (In a stern voice) 'Don't talk about things, show it' (laughs). It is a visual medium.

The first time I turned on a camera and heard the characters, I thought that people talking revealed a lot; that was as interesting as any landscape.

I'm not that verbal myself. I'm not much of a good talker; I'm more of a listener.

When you fall in love with cinema, it's usually visually, but it's just the way you evolve. Like I said, I'm as surprised as anyone!

When I was making my first film, I thought strictly in visual technical terms; I wasn't thinking so much dialogues or character, even though I had a background in theatre. I should have known that was coming.

I never improvise on camera. Never. Ever. That's never made sense to me, I don't know how to do that. It's always very scripted and rehearsed. You know, it can be a loose idea, I can sit with the actors, but by the time the cameras are rolling, we have worked it out. We know what we're doing. I don't leave it to chance.

Q Even with your fascination with dialogue, you don't just direct to, say, deliver the poetry of a script, as in the case of an Aaron Sorkin movie. You take direction very seriously, don't you?

A Yeah, I mean, cinema is the most important.

I remember every movie of mine having a little cinematic scheme in mind—visually. I mean, I'm not, like, uber-stylist; I'm not that interested in that. But I do really believe in a cinematic design to the story you're telling. And you spend a lot of time to work on it. I think people who come strictly from writing backgrounds, might not think that way.

But I always felt that it was primarily a director's job to think cinematically, in terms of pictures and stuff, you know? What's the particular tone, style, approach to a movie—I'd have really strong rules in that area. I plan all that, even though, again, it doesn't drive too much attention to it I hope.

But, you know, it's about creating a parallel world of characters and trying to make that work when it all comes together in the movie. I don't see anything as separate; [it is] all part of the same thing, which is trying to tell the story appropriately, and that's different from film to film.

Q Comedy has also always been an important part of your films, even when you are dealing with subject matter as serious as death (Bernie) or drugs (Waking Life).

A I think it's just the way I see the world. Everything's funny, you know! I've done a lot of comedies where most of what I do is pretty comedic, but Bernie was a challenge because it is about death. There is some dark subject matter swirling around that movie. But I think to make that a consistent comedy was a real challenge. That world's so much like ours, even though it's tragic [and] there's a lot of ups and downs. I think it's not a bad way to see the world through a comedic lens. Whatever tragedy, hardship or struggle, comedy is a pretty good way to offset it. And not more consciously—again, that's just in films—but in the way you naturally see the world, I think, and the way you approach drama too. I just can't help but see the humour. And I admire that in movies I like.

For example, Raging Bull is a movie that would never be listed as a comedy.

It's just too dark a subject and what you take away emotionally from that movie is anything but comedy. And yet, if you really sat down in front of it, you would find yourself laughing very consistently throughout that movie.

And I thought that was brilliant! I mean, when I saw that movie, something clicked in me—this was before I was even thinking about making movies [myself].

It's kind of like how I see the world: in the middle of fights, in the middle of all the horrible stuff, I would have these funny thoughts. Even as a kid, when things were bad, or parents were mad at you, there was always something ridiculous about it, something funny. I always liked that tone.

So even with Before Midnight—people wouldn't think that film's a comedy, in fact it's an extreme opposite of it—when they fight in the movie, Julie and I think that's pretty funny. Celine and Jesse don't think it's funny, far from it; but we, the audience, do. And I like that mixture—a little uncomfortable, a little real. I think it's the right approach to a movie and to life.

Q Do you ever find it surprising that living in Austin, outside of Hollywood and the studio system, you have managed to have such a spectacular career?

A Yeah, well that would be my point of view—and I guess it's yours—but Hollywood wouldn't look at it that way. They would look at my career as an underachievement or a failure, you know. Whatever (chuckles). It's all perspective.

When I go to LA, I do feel like a nobody, because I don't fit into that world so well, you know. I haven't made all that money. What I mean is that our concerns are not exactly the same. They are sometimes, yes, but it's nothing I think about a lot.

It's just the way it all worked out. I'm lucky to live in my own bubble and managed to make a life and living out of my kind of cinema. I've been lucky to get a lot of films made, because it's hard to do, and it's harder to do today. I think I came around at the right time. It would be tougher to get started now, doing what I've been able to do.

Q What would it take for you to come back to the studios? A superhero film?

A (Laughs) I don't know about super heroes, but I'm always on the lookout for comedies. You know, when you are trying to get a story told, some need a bigger budget and studio backing because some are inherently more commercial. So obviously, I'm not averse to that.

School of Rock and Bad News Bears are good examples in the last 10 years of times I found myself way into a story where I felt I could express [something] or I was the right director for, but those are probably the only two films [I have done] that maybe would have existed without me. Like, if I wouldn't have done them, someone else would have. None of my other films would exist as movies, you know, if I wouldn't have done them. But those two, they are part of the system.

But I like the system. It's nice to have that support. They have $30 million, a 50 day schedule, you can do it right. It's kind of nice to have the—if you're lucky enough—subject matter they think it warrants. Usually, I'm in the area where they say, 'Oh! This isn't a very commercial movie; we've got to do it for nothing!'

That's okay, but that's tougher over the years too. Bernie would have been a studio movie 10-15 years ago, but by the time I did it, it was like an [off-beat] independent movie.