Anupam Kher: Loser, Fighter, Winner

IN ALMOST EVERY individual’s life,’ writes Anupam Kher in his recently released autobiography, ‘there comes a watershed moment.’ His came in 2011.

At the time, a group of activists led by Anna Hazare was at Jantar Mantar in Delhi to protest against corruption under the then Congress-government. Kher was convinced that if he wanted the movement to get wings, he needed to participate too.

This was his first brush with political activism. The Lokpal created subsequently was a watered down version of the one envisioned by the activists. But Kher felt more let down by a section of protest leaders who, led by Arvind Kejriwal, decided to form the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) and enter electoral politics. He was further distressed to see them forming a rocky alliance with their political foes, the Indian National Congress, after the Delhi assembly polls.

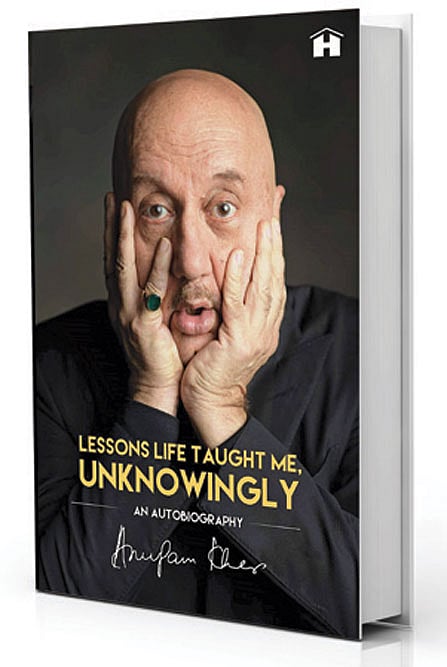

‘Then came Narendra Modi!... I observed that he did not talk like a regular politician and only spoke about his vision for India... He broke the cliché of a typical politician and installed hope... Being an eternal optimist, I sought refuge in Narendra Modi’s vision and wished that he becomes the prime minister of this country,’ he writes in Lessons Life Taught Me ,Unknowingly (Hay House India; 432 pages; Rs 699).

In the 2014 elections, the BJP romped to victory with an electoral campaign focused around Modi. The party also won a seat in Chandigarh, where Kirron, Kher’s wife of 34 years, was contesting. In the years since, Kher—like his contemporaries Vivek Agnihotri, Kangana Ranaut and Ashoke Pandit—have chosen to wear ‘patriotism’ and pro-government sympathies on their sleeve. Modi critics, Kher likes to say, have an “agenda” and “cannot handle a chaiwala becoming a Prime Minister”. He’s called Nandita Das a “spokesperson of Pakistan”, questioned if Arundhati Roy “is even Indian in the first place” and slammed Aamir Khan for expressing fear about the rising intolerance in the country.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

‘I am able to express my opinions on politics or current affairs, fearlessly, only because I have the power of a common man within me,’ he writes, ‘without any allegiances’.

But it may seem difficult to take Kher for his word. His autobiography is a testament to that.

An autobiography, one may argue, is the compendium of all narcissism. And yet Things Life Taught Me, Unknowingly is striking in its self-indulgence. In it, Kher celebrates Kher, a ‘destiny’s child’; born in poverty, raised with integrity, hurtling from one challenge to another, overcoming all odds and achieving everything.

It has moments of self-deprecation. There are also occasional self-indictments for ‘strutting around like a peacock’ and being ‘a victim of my own success’. But overall, its telling lacks heart. Kher rarely allows us peeks into his vulnerabilities, lesser still into his insecurities. Some of the unflattering parts of his life—when the sister of an actress accused him of molestation in the 1990s; the controversy he racked up in 2011 saying that the constitution “wasn’t an irrevocable document”; his tenure at the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) and Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), wherein he was accused of leading a ‘repressive regime’ — are glossed over or conveniently forgotten.

Kher comes across as someone you’d be awed by, intimidated by even, but not like or relate to. He’s also prone to bouts of self-congratulations. ‘I do count myself as a star in my firmament, an author in my space and a teacher with a voice,’ he writes. ‘I have become a multi-dimensional avatar and have preserved onwards through life’s interesting journeys. I am proud of how far I have come and there is no stopping me.’ At another point, he writes, ‘I want to thank myself for living life the way I did.’

But then, Kher does have a lot to be proud of. In his four-decade career on stage and screen, he has acted in over 530 films, written two bestselling books, staged an autobiographical play, launched an acting school and successfully crossed over to the West. He’s the only artist in India to have chaired the CBFC (2003-04), National School of Drama (2012-2014) and the FTII (2017-2018). His willingness to straddle art and melodrama with élan—be it a headstrong police commissioner in A Wednesday (2008) or the conniving kabadiwala in Dil (1990)—has made him a staple presence in Hindi cinema since 1985.

Despite his ferocious talent, Kher has seldom carried a film solely on his shoulders. His premature baldness—which he doesn’t directly address in the book—meant he was most often offered characters far older than his age. You’d be hard-pressed to find any leading actor over the last four decades Kher hasn’t played a father to. Such pigeon-holing, Kher insists, didn’t bother him. His versatility and networking skills helped him land plum projects in India and Hollywood, including the Academy Award nominated Silver Linings Playbook in 2012. Today, he’s pals with the likes of Robert De Niro. Last year, the Hollywood legend even threw him a surprise birthday party.

It’s remarkable then that it all started with a blasé reply to Mahesh Bhatt, hearing which the director cast him as the lead in the path-breaking film Saaransh. In 1983, when 28-year-old Kher was shuttling between film studios, he was invited to meet with Bhatt at the director’s residence. “I have heard you are quite good,” Bhatt said. “You have heard it wrong, sir,” Kher replied. “I am not good. I am brilliant.”

Wasn’t that a rather blunt remark for a newcomer, I ask Kher over the phone.

“The only thing you have with you is the truth,” he replied. “Mahesh was an educated director who was making a casual statement that I’ve heard you’re good. I felt I needed to correct him. That’s how I’ve been all my life.”

Kher now lives in New York. I was allotted 30 minutes for a telephonic interview during his early morning hours. Minutes in, he was clear he didn’t want it to be a “political” interview. I’m bound to do that, I told him, he’s made far more headlines for his politics than his performances off late.

“But then this interview could’ve been a straight interview,” said Kher. “You don’t have to know about my life to do this.”

A member of Kher’s PR team, a silent presence in our three-way international call until then, crackled in: “Omkar, can we please speak more about the book?”

“No no no no no,” said Kher urgently. “Don’t worry about it. I’m just trying to put across my point of view... I am an open person. I say what I feel. I’m okay talking.”

But he wasn’t. At one point, I asked him to clarify an unusually candid excerpt from his autobiography pertaining to the ruling party: ‘All those should be arrested who have been behaving arrogantly (ranting against the minorities, mainly the Muslims), whether a sadhvi or a yogi. There are some members in the BJP who speak nonsense.’ Kher clammed up.

“I refuse to answer that question,” he said.

“I want to understand where you are coming from,” I replied.

“Just say that Anupam Kher refused to answer that question. I’m giving you the liberty to say that.”

I do have questions that go beyond the book, I told him. That is the whole point of an interview.

“If that isn’t in the book, I’m sorry Omkar, I don’t think I want to answer it... because the interview I’m giving is about my book, I’d like to stick to the book.”

I attempted no further negotiations. Instead, I took up his manager’s offer to email him questions post our phone call. I haven’t received a reply.

It’s not unusual to find Kher sounding irascible. His straight talk can often be construed as arrogance, he likes to say. He makes no apologies for the self-aggrandising parables littered through the book. He’d rather stand by his words and choices even in the face of opposition.

In 2014, Kher claimed that during his time as the CBFC chief, he “single-handedly” cleared The Final Solution, a documentary on the Gujarat genocide. (Kher repeated that claim during our interview). Rakesh Sharma, its director, however, rejected the claim, and accused Kher of harassment and attempting to stop its screening in Bengaluru. His year-long stint as the chairperson of FTII too was marked by censorship, surveillance and a susceptibility to toe the government’s ideological leanings.

“There’s lots of unresolved issue in India, in your house, in Open magazine,” he said instead. “If anyone wants to take knowledge from institutions as these, there’s millions of possibilities. If students say mujhe kya mil nahi raha woh chahiye, woh apna perception hai...”

Another crucial aspect of Kher’s political identity is his advocacy of the exiled Kashmiri Pandits. Kher belongs to the community, although his family moved to Shimla from Srinagar two years before he was born. His advocacy, however, seems low on communal reconciliation and high on chest-thumping nationalism. This is most evident in Kher’s own narration of his visit to Kashmir three years ago.

In March 2016, students at National Institute of Technology, Srinagar, clashed over the outcome of an India-West Indies cricket match. Incensed by their Kashmiri counterparts’ support of West Indies’ victory, some students took out a tricolour march and burnt a Pakistani flag.

‘In volatile Srinagar, such acts are considered hostile in several quarters,’ Kher writes. He then decided to travel to Srinagar. ‘My agenda was clear. I would go to the NIT and wave the tricolour there, after a fervent appeal to national pride.’

Kher was detained at the airport by the state police. His appeals to the personal secretary of then chief minister Mehbooba Mufti and to a “high political figure in Delhi” made no difference. Eventually, he was sent back from the airport. It’s thus no surprise that he’d be supportive to the constitutional changes made recently to integrate the state of Jammu & Kashmir in mainland India. ‘Kashmir solution has begun,’ he tweeted soon after, in an apparent reference to the Nazi concept ‘The Final Solution’ that led to a genocide of Jews.

“Did you not anticipate [going to Srinagar in 2016] might create problems?” I asked. “Surely, that thought must’ve crossed your mind.”

“Not at all,” said Kher. “I thought the [police] had come to receive me. Then they said, ‘You can’t go in at all.’” But even the BJP, part of Mufti’s coalition government at the time, wasn’t in favour of it. A party member told The Telegraph, “Even if he did not say anything provocative, his presence on the campus could have sparked off tensions, more so because he is one of the most outspoken voices on nationalism.”

Three years on, Kher feels just as strongly about it as he did then. One could almost sense his schadenfreude when he said to me, “When Ghulam Nabi Azad or Rahul Gandhi says that they weren’t allowed in [the opposition leaders were similarly detained at Srinagar airport recently], it’s a great reference that a Kashmiri pandit was not allowed to get into that place.”

Does he alienate people with his polarised views? I asked.

“How does it matter?” he said. “I live my life the way I want to live. I have the courage to defend myself. You cannot be popular with the whole world. The people who matter to you, if you are popular with them, you’re fine.”

With 14.1 million Twitter followers, Kher clearly has a fan base. In this legion, one stands out. You’d find him in the Acknowledgements: ‘This is me, Anupam Kher, the small-town boy, the loser, the fighter and the winner all in one.’