Ways of Seeing

The works of five artists that illustrate the semiotics of modern and contemporary Indian art

The semiotics of modern and contemporary Indian art signals diverse ways the artist sees the world around him. It is layered with the personal history of the artists, their ideologies and the trajectory of their society. The visual language spans a gamut of expressions, from the romantic to the ironic. And with the exception of the abstract artists, the images are replete with metaphors. The works of five artists in the collection of the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) illustrate these points.

Woman Holding Fruit, 1880s, Raja Ravi Varma

Raja Ravi Varma (1848–1906) was a remarkable painter. Born into an aristocratic family of Kerala, Ravi Varma largely taught himself the skills of oil painting. It was a medium introduced by the British and was just beginning to be mastered by Indian artists in the 19th century. The Indian elite of the times, who formed the bulk of the patrons, were attracted to the new medium. Ravi Varma's genius lay in that he had not only mastered the technicalities of the medium and used it brilliantly to represent an Indian ambience, but also that he understood the tastes of the patrons very well.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Ravi Varma specialised in three genres—portraits, history paintings and romanticised representations of beautiful women. Woman Holding a Fruit is a superb oil on canvas from the last mentioned genre. A fine rendering of a young girl holding a fruit, he captures the figure with a degree of tenderness. Right from the bracket figure of a woman holding on to a mango tree bearing fruit on the eastern gate of Sanchi stupa, women with fruits have encoded fertility. In other mythologies, women's association with fruits has been symbolic of the consciousness of sexuality. Ravi Varma ingeniously balanced innocence and sensuousness when he painted the fresh-faced young woman holding a succulent fruit. The girl is painted in soft pink and brown tones and her colouring is enhanced by a string of red rubies against her silky throat.

In keeping with contemporary taste, Ravi Varma's rendering of the girl was naturalistic. But he did not borrow British techniques blindly. Instead, he experimented with the palette to achieve a skin tone suited to the Indian complexion. Similarly, the lighting was right for an Indian setting.

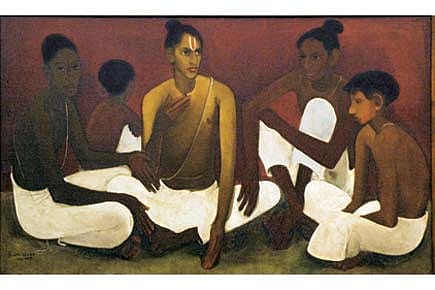

The Brahmacharis, 1937, Amrita Sher-Gil

Amrita Sher-Gil (1913–1941) had a different way of looking at India. Born of an Indian father and a Hungarian mother, she grew up largely in Europe. She received her academic training in Paris and in those early years, painted in a richly expressive European style. But when she returned to India in the mid 1930s, her way of looking at the country changed her visual language radically and she made bold experiments with her palette and figuration. Following a visit to Ajanta and places further south, she did a number of paintings with attenuated, stylised figuration, accentuated with large mournful eyes. The Brahmacharis is a striking example of such a style. The carefully structured composition of six young male figures carries a hint of monumentality in the arrangement of the elongated central figures. The variations in rich brown skin tones and the dramatic use of a dazzling white not often encountered in European oils show her readiness to experiment. The sad, austerely beautiful males reveal Sher-Gil's engagement with India and Indians.

Mother Teresa, 1988, MF Husain

Maqbool Fida Husain(b. 1915), one of the leading figures of the Progressive Artists Group, stressed the importance of form in a painting. Given his early experience as a painter of cinema hoardings when he first came to Bombay, it is not surprising that he endowed his figures with a feeling of monumentality.

In spite of the simplifications of form and use of geometric lines and shapes in structuring the figure, Husain invested his peasants and villagers with immense dignity and humanism. It must be remembered that he was beginning his life as an artist when a newly independent India was filled with hope and the country had thrown itself totally into a nation-building project. Husain's images, besides their use of form, colour and texture in a radically new way, also spoke in a language of metaphors.

One of his earliest mural-like paintings, Zamin (1955), validated the symbols of a rural community of peasants and artisans through paintings of bulls, horses, wheels and so on. But by the time he did the large Mother Teresa painting, he devised an even more complex imagery through which he expressed the contradictory pulls of youth and age, of mortality and new life. Above all, there was the over-arching figure of the compassionate mother drawing the opposing elements within her. One must also remember that Husain lost his mother when he was a mere infant. The mother has been a magical figure of fascination in many of his paintings, at once alluring, tender and nurturing. Mother Teresa shows yet again Husain's command over bold, vigorous lines and forms.

Untitled, 1969, Vasudeo S. Gaitonde

Vasudeo S Gaitonde (1924–2001), one of the early modernists, turned towards abstraction early in his career. His search for a non-representational style of expression was not born out of a revolt against political turbulence, as it was in the case of European abstractionists in the early 20th century. He was not attempting to re-order contemporary reality into an ideal, Utopian construct like Malevich and others. Instead, having an introspective bent of mind, he seemed to be embarking on a metaphysical journey on the nature of self and beyond.

The large painting in the NGMA collection highlights the Zen-like contemplation that is characteristic of the best of Gaitonde's works. Under its meditative tranquility, there is a lot of surface activity in the large field of colour. There is tension between the horizontal and the vertical, between amorphous, amoeboid forms and minute detailed texturing—a scratched-out squiggle here, a minute form there. The golden yellow colour that dominates the painting is nuanced with a subtle play of darker undertones and glinting highlights. It invites the viewer's gaze to travel slowly over the surface and try to unravel the inner state of the soul.

Three Cows, 2003, Subodh Gupta

Subodh Gupta (b.1964) is very much a part of this trajectory of modern and contemporary Indian art and a departure from it. Born in a small town of Bihar, Gupta captures the dynamic energy, brashness, violence and the vulnerability of small town life in India. His images take an ironic look at transition and, at the same time, empathise with the displacement and the alienation. He sets up a dialogue between the urban metropolitan gaze and the provincial way of seeing. While Husain casts his rural India in a heroic mode, Gupta prefers to take an enigmatic, quizzical look. And like the best of Indian narrative tradition, he expresses himself through metaphors that are sometimes easy to read, at other times oblique and elliptical. The Three Cows shows three bicycles with milk cans. This is a common sight in cities where scores of bicycles bring in milk from peripheral areas. To urbanites, the milk cans produce the milk that they need. The cow yielding milk has become an abstract concept.

Gupta gives an iconic status to these mundane objects, subverting the way we look at things. To heighten the irony and subversive comment on the relationship between metropolis and peripheries, the aggrandisement of one at the cost of impoverishment of the other, he uses a style of super-realism, where he works on his image from an enlarged reproduction and works in his comment with a light touch.

Rajeev Lochan is director of the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi