The Shape of Emptiness

Writer Siddharth Dhanvant Shanghvi's most ambitious work captures a life in transition, and in a new language too

The day after Siddharth Dhanvant Shanghvi's exhibition of photographs opened noisily at a cosy space in Mumbai's Ballard Estate, Matthieu Foss, the tall Frenchman whose will runs the gallery, stood before an image of a clothing line. Foss gestured at a picture of the writer's clothes hung beside his father's, and said, "You know, I like to think this is homage from a son to his father." The House Next Door, Shanghvi's exhibition, is about his father, who features in many of the 27 monochrome pictures on display. But it's just as much about a widower, about a man affected by brain cancer, and about how these calamities forced new meaning into the simple acts that make up the days of our lives.

In one image, Shanghvi records his father seated alone on his bed. He wears spectacles, and looks on at a scene we can't see. We can't see his eyes, but we can interpret his thoughts, and just as well infer emptiness. His shape weighs on the frame. His burden weighs on the room around him. What he sees is unimportant. This is what Shanghvi sees. Few other pictures here portray the burden and guilt of his father's loneliness as elegantly as this one. His father is here, but he's also someplace else. This bothers Shanghvi, for he misses his father's old self. It's a self that shaped him, and those traits, now gone, force the writer to come to terms with his own mortality; when the memories associated with a time fade, that time is lost too. 'He had a temper that terrified us,' Shanghvi wrote in his introduction to the show, 'which we were relieved to see go: the chemo blasted it away, along with everything else… But without his temper, he was difficult to realise, and one afternoon my sister pointed out that all along, our father had been waiting for us behind it. This gentle, slightly befuddled and disarming man was who he really was. And now without his anger he seems unfamiliar to us.'

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Shanghvi has a masters in photography, but remained unconvinced about his work until he was persuaded to exhibit his photographs. This project began as a visual diary after his father's diagnosis. Shanghvi's efforts found a man grinding out time.

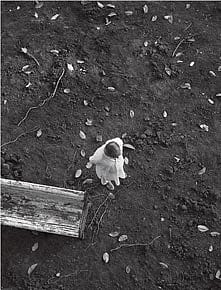

Shanghvi's dominant theme is of the emptiness of a life, but he makes room for joy. He captures Bruschetta, his father's dog, mid-motion on a lawn from above, with a winding hose cutting through the grass like the outline of a speech bubble. One of the photographer's more graphic compositions, its lightness of spirit contrasts starkly with the mood that pervades his father's home and these pictures.

Bruschetta, it turns out, photographs well. Posing for a memorable photograph of his owner's feet, the animal, taut and alert, thrusts its snout downward behind old toes pointed to the sky. Metaphors abound. In another, Bruschetta sits for a portrait on a chair. Families change.

Shanghvi's novels are unrestrained and lush, and bulked up by his penchant for serious exaggeration. But Shanghvi's photography is another matter. To write fiction requires searching and reaching for a thing that isn't there yet. To take pictures in the style he prefers is to wait for a thing to form; a moment, a feeling, an understanding. He waits for the quiet poetry of moments. At times they come as abstractions, apparent in pictures taken from above or below: his balding father, dressed in a kurta, takes a walk in the building's compound assisted by a helper who clasps his hand. Sometimes they come as startling compositions: his father's head, seen from below, sticks out from a balcony. No body. Just a head with glasses.

His father's routines gave Shanghvi room to explore. In one image from the side, his father sits on an old swing alone, staring straight ahead, his body slouched, and his hands holding on to each other. In another, taken at a low perspective from behind, he walks alone outside, his left arm gripping his right elbow around his back, with the fingers of his right arm pulling at a kurta sleeve. At the moment of his preservation his posture is awkwardly tilted. In another, his father eats alone on a long table built for ten. But the sadness in this picture comes not from his loneliness, but from that grand chandelier above the table. More heartbreaking than loneliness is decline. Shanghvi explains this with feeling in his introduction. 'I do not want to wait so long that my nights become sleepless and my afternoons full of unbearable solitude. So the photographs have me thinking about not only my father's end but also my own. A timely retreat ought to be uninfluenced by either age or sickness. Leave when you are not interested in the life around you. Don't wait so long that life is uninterested in you.'

Of course life has a stake in us all. If not for our vitality, then for our usefulness as test subjects, like taps turned ten thousand times before they squeak. Shanghvi, who recently lost his mother, now witnesses the gradual absence of the other parent. He sees 'afternoons full of unbearable solitude'. He does not want to 'wait so long' that his 'nights become sleepless'. This dread seeps through his photographs, nowhere more so than one where his father stands outside, surrounded by fallen leaves, and considers the barren earth beneath.

The day after the opening, silence allowed a visitor to truly feel the photographer's work without distraction. Here was a lonely father. Here was a dog. Here was a meal taken alone. And here was an empty room; merely an empty bed in an empty room. At first. A closer look revealed what Shanghvi saw. A four poster bed, with two sets of pillows. One pillow was ruffled and depressed, the other was immaculate. One half of the mattress was pressed down, while the other half kept its shape. The detail. The most incredible detail.

The House Next Door will run at Matthieu Foss Gallery, Mumbai, till 26 February