The Instinct of Aamir Khan

How he understands his audience, how he managed to tame the media and why he is a different man.

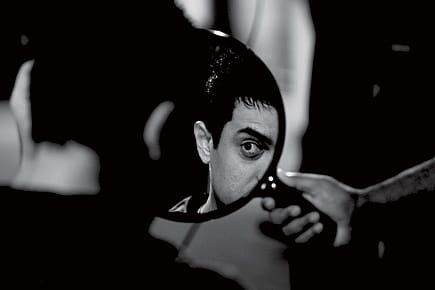

Most men will die one day without ever using a puff. Aamir Khan is not among them. Bearing the same authority of a surgeon extending his hand for a scalpel without looking up from the body, Aamir says, "puff". Nothing happens for a while, as if the existence of something called a puff is a figment of his imagination. But then a man appears with the puff and a circular mirror. Aamir sets aside the enormous book, Mohandas by Rajmohan Gandhi. And you would think he is going to chuckle in male shame, but he does not as he powders the region under his large translucent eyes which somehow look very expensive. He has probably not slept well in the days before and after the release of 3 Idiots. He has travelled all over the country in various disguises to startle the general public and in that way offer something new to journalists, part of his many devices, ethical devices as he would point out, to ensure a relentless coverage of the film in newspapers and on TV channels.

Before a release, filmmakers usually pay money for flattering coverage in newspaper supplements. Star rumours are manufactured for publicity and some minor mishaps are choreographed. Films are declared hits even before they are released. Aamir says he does not have the heart to do such things. He would play the marketing games, of course, but they would be hard won. He would not negotiate a compromise with his own values. He is not fully infatuated yet with that overrated human quality called practicality. Also, after a two decade long "relationship in the dark room" with all kinds of Indians, it is below his dignity to have to pay to be written about. Or to do things that he believes have no meaning. He still does not participate in Filmfare awards. "That award has no value," he says.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

It does not mean he is not cunning. In the surprisingly modest Bangalore hotel where he is staying, as Aamir walks down its corridors, or stands in its lobby or even in the lift, he is constantly dispersing the latest collection figures of 3 Idiots. "It's going to earn more than any film in the history of Indian films." Surely, he knows figures have to be adjusted for inflation rates before one arrives at such conclusions, but he also knows the power of repetition. In the years when he was in his bunker of private grouses and rage against the media, he had seen other filmmakers do it successfully—keep repeating figures until they become common knowledge. However, independent enquiries with the trade confirm that 3 Idiots is an extraordinary success.

For Aamir, the commercial success of a film is a reassurance that his "instinct about my own people" is still sharp, and that the new world has not left him behind. Like all stars, Aamir makes an unspoken distinction between the faceless masses, whom he loves and wants to impress, and the visible fragments of the same human monolith, who want their photographs taken with him, who annoy him. He has developed tactics to save himself from the fragments. He does not maintain eye-contact and tries to appear unfriendly, and does not feel it is rude anymore to tell strange women that he would not give them his mobile number. But the audience, "the people", he loves them, he wants to know them. He still persists with the tradition of making clandestine visits to halls where his film is running. "Earlier, I used to go in disguise. Now, I enter the hall when the film has just started, when the hall is dark. I leave before the interval and visit another hall. I manage to visit seven or eight theatres in a day. I have seen people dance in the aisles. I have seen people squirm. When they squirmed, I have cried."

It is said that getting Aamir interested in a film has the excruciating agony of waiting to win a girl's affections, and his acceptance comes with the greater torments of a woman's terrifying obsessive love. "He is involved in every aspect of a film," a director says, "Some might not like that. He does not trust anyone, it seems."

Most of the time, though, Aamir rejects the scripts. One such writer who was rejected remembers a whole evening he spent in Aamir's home trying to sell him the idea. "I was nobody then, but Aamir spent a lot of time with me discussing the story. He had so many questions. So many doubts. 'Would this work, would people find this convincing… I know people and the people won't accept it'. He didn't know me at all, but we went to the toilet together and we peed standing side by side, talking about the script. In the end, he said 'no'."

Aamir says that he does not waste the moments of his life doing anything he does not love enough. "When I am choosing a script, I don't think of the audience. I think of myself. I have to love it. Then I think of the audience. I wonder how can we tell this story without boring anyone. I have only one interest in a film. The message is not important to me. What is important is that I don't bore you. I know what you want is entertainment. The only responsibility of a film is to provide it."

In the hotel room, he searches for a piece of wood. "Touch wood," he says, "Every bad film of mine has flopped. Imagine if they succeeded. I would be so confused. I would not know why I am here, or what I must do. I would not know why I succeeded. Isn't that terrible? Not knowing why you have succeeded?"

As he says that, there is a glint in his eyes that suggests he is seeing in his mind the high resolution images of some actors whom he would not name. Aamir, despite his image of largely minding his own business in his private world of triumphs and wounds, is an extremely competitive man, as competitive as Shah Rukh Khan. He doesn't say it, but he believes he has the right to be considered the greatest of his time. His gift, he says, is his power of observation. "I am very curious about people, their mannerisms. I am a bad mimic, but I can adapt well." He says an actor can either live like a star or be interested in people. "I am interested in people. Even now, I am observing you. I know what you are doing. I know what the photographer is doing. I am not researching. I am just looking. I may use it somewhere in the future."

When Aamir speaks, he looks at you. It might seem like an unremarkable quality, but the truth is that an extraordinary character of the Hindi film industry is that most of its stars do not. With Shah Rukh, for instance, when he talks, you get the feeling you can slip out of the room and come back, and he would still be talking. That is why Aamir claims that one of his greatest gifts is his relative normalcy, a mental balance that is hard to maintain in the unsettling life of a star. He exaggerates when he claims that he does not behave like a star or think like a star, but he is convincing when he says that he has the capacity to be normal. And why it is a special character in the Hindi film industry can be fully comprehended only when we understand others who are as famous and powerful as him—his contemporaries, his rivals, his "competitors" as the word accidentally slips out of his usually careful mouth.

About six years ago, Shah Rukh Khan told me in a low calm voice, in introspection over his own ageing and future, "Will I insist on acting with young girls to hide my age? Will I ever address myself in third person like these film people end up doing: 'Shah Rukh is impressed with you. Shah Rukh is angry?'" It was actually a satire on other actors who have done all this. Curiously, he has now begun doing exactly that, including addressing himself in the third person. Sanjay Dutt and Salman Khan do not attempt to hide their estrangement from reality. When I met Sanjay Dutt during the shoot of Munnabhai MBBS, he sat on a stool and told a shrub, "Some people make me work too hard, they are pushing me, brother." The only time I have met Salman Khan, he was sitting bare-chested and cutting his own finger nails with a blade, and tried to appear menacing but that only made him laugh. And, Sunny Deol, at the height of his commercial worth in the years that followed Gadar, told a director who went to narrate a film, "I cannot die in the end. The Deols don't die." It is in the face of many such stories that Aamir appears normal.

For his tenacious link with sanity, for his perpetual curiosity about the Indian population, for his love for cinema which comes before his love for money, and for his indescribable instinct about what would work on screen, Aamir Khan craves acknowledgement. And he would really like to walk on a stage and collect an Indian film award that was not a farce. "I miss that," he says. But, there is an award that he respects. He even went to Chennai to collect it. It is a film award not many people have heard of. The Golapuri Award is given once a year to the best debut director. It is promoted by a family in Chennai, and dedicated to their son who had died while filming his first film. Aamir won the award for Taare Zameen Par. "I like the seriousness of the award," he says.

The absence of a truly coveted national award forces him to consider the media as the next best form of recognition. He looks wounded when he talks about the media, and it is not the wound of an old animosity as commonly believed, but of a perpetual infatuation. He wants the affections of the press because "it's a bridge between me and the people", and he is unable to accept its occasional betrayal. Like Sachin Tendulkar, he was once known to be unforgiving and to blacklist journalists and magazines. The behaviour of journalists during his marriage to Kiran Rao repulsed him. "Cameras tried to zoom into our house. That's not fair. My marriage is private." Also, he believed that his rivals were manipulating the media to declare his films (like Mangal Pandey) failures after their first day of release. "So, for a period of time, I decided not to speak to the media." But now he has changed. "Something strange happened which made me change my view of the media." And it happened, improbably, when he went to meet a doctor.

"I was researching Taare Zameen Par and this doctor told me something interesting about what parents should know about what children want. A) They need security. They have to feel secure all the time. B) Trust. You have to trust them and trust them honestly. If your child says he has not done something, then trust him. C) Dignity. You have to treat your child like a human being. D) Love. But without the other three, love is meaningless. When I heard this, the first thing that came to my mind is, 'I need these four things, too. Not just children. I need to feel secure, I need to be trusted, I don't like it when you insult me and I need a lot of love.' Then the thought came to me that even the media needs the four things. I decided to apply what I learnt to the media. I think it worked. My relationship with the media is better now."

An interesting consequence of Aamir Khan reaching out to the media is the lesson that the overwhelming charm of a Hindi film actor would obliterate all opposing forces, including the English media's very own synthetic darlings. That Chetan Bhagat had a grouse, any grouse would normally be news in these starved times. That he would have a grouse about how he was not credited in any significant way for 3 Idiots should have been news. But Aamir's gigantic shadow over the media has made Bhagat's complaint go largely unnoticed. "They (director Rajkumar Hirani and probably his conscience) say the film is only loosely based on my novel," Bhagat says, "But I've seen the film. Scene after scene is from the book. I've been credited at the end, after junior artistes. I don't know why they have done this. They kept me out during the making of the film. I asked for the script. They didn't give it to me."

Aamir Khan says, "I've not read the book." It is common for a film script to change many times, he says, and in the end the film had no resemblance to the novel. But he is clearly not interested in talking more about the subject. He implies it is a minor issue and that nobody was wronged. "We bought the rights and credited him as it was mentioned in his contract."

Aamir's formidable media presence at the time of the release of his film also overshadows directors and producers. Rajkumar Hirani, despite his fame, is clearly not the voice of 3 Idiots. Even the film's producer Vidhu Vinod Chopra, not a shy man at all, a man who loves himself immensely and had described himself in the first version of his website as someone who was 'trapped in his own brilliance' from early childhood, had to let Aamir take over the marketing of the film. Aamir's predominance and the fact that in recent times he has not worked with a director twice, gives substance to a common perception in the industry that he is a difficult man, and that directors are wary of him. "Not true," he says, "Those directors want to work with me, but they don't have a story that interests me."

The fact that Aamir chooses his films carefully has created a perception that he is a cerebral actor, but there is also a surprising intellectual austerity in him which might be a gift in the world he occupies. His films are simple and accessible not because he has made an artistic compromise, they are that way because he too is simple. This quality is best explained in his own perceptions of his film Ghajini and its inspiration, Memento. Directed by Christopher Nolan, Memento is based on a short story by his brother, Jonathan Nolan, and is a story that moves back in time about a man with a short-term memory loss condition who seeks revenge for his wife's murder. There are those who consider Memento a work of rare precious genius, and those who do not understand it. "I didn't understand it," Aamir says, "It bored me." It is a statement that would disappoint one of the two kinds of people in the world.