The City, the Stroller and the Comic Strip

Three artists explore the joys of city strolling and mining its stories. On display under a single roof in a Bangalore gallery are the pleasures of flânerie

In Edgar Allan Poe's short story The Man of the Crowd (1840), a nameless protagonist follows a 'decrepit old man' through London's crowded streets. The old man walks endlessly through bazaars and shops, and the poorer parts of the city. Eventually he makes his way back into the heart of mighty London, while the protagonist, from sheer exhaustion, ceases to follow him any further—'He refuses to be alone. He is the man of the crowd.' Poe's walkers closely fit the idea of the flâneur, a French word which means 'stroller', someone who saunters.

Contained within the act of walking is the act of looking—to watch, to be both participant and observer of the city. Although now a popularly recurring motif in urban literature, sociology and art, the flâneur of nineteenth-century Paris was initially given shape in Charles Baudelaire's prose and poetry. Later, German philosopher Walter Benjamin transformed the flâneur into an object of scholarly interest. Yet the walker is not a benign creature, merely abandoning himself to the streets. Scholar Fiona Penikwer, in L'Homme des Foules: The Vampiric Flâneur, touches upon the parasitic aspect of the flâneur—'dragging the crowd for intellectual food or material for his latest novel'. In Gallery Ske's 'The Flâneur in the City', we see how flânerie, or the act of strolling, has inspired artwork and stories by three Indian graphic artists.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The show is curated by Gokul Gopalakrishnan, who wrestles, as many superheroes do, with a dual life—he is an inspector at Kerala's motor vehicles department as well as a comic artist who sketches weekly columns for The New Indian Express and DNA. The idea behind the show, he says, is to explore the possibilities of comic art beyond the pages of a comic book. "The placement of comic art on gallery walls not only subverts the familiar gallery viewing experience, but also goes a long way in levelling the so-called high/low art divide."

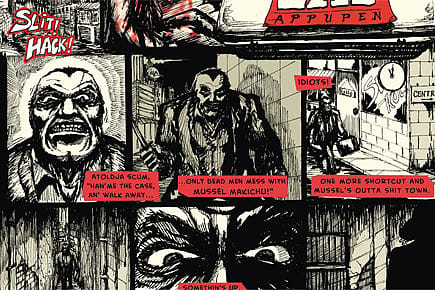

The works on display are by Gopalakrishnan, EP Unny, chief political cartoonist with The Indian Express Group and author of several graphic stories in Malayalam, and George Mathen, also known as Appupen, a Bangalore-based visual artist and author of graphic novel Moonward. Their graphic stories adorn the gallery in stark simplicity, with images and text spilling out of their frames, utilising the walls as part of a larger canvas. This is evocative of street graffiti and helps integrate the gallery space with the narrative of the artworks. Within the display rooms, the area is mapped out like city streets, with traffic cones and barriers manipulating the way visitors experience the space.

As Gopalakrishnan explains, "I've always felt that reading comics is akin to strolling in a city, where the gaze is not linear but constantly shifting to accommodate a multiplicity of visual experiences. Reading a comic is not linear either, as you try to experience the narrative (in your own way) by oscillating between image, text, space, time and panels, and even pages." Given this, the flâneur was a natural choice, for he or she walks the city in order to experience it. The stroller in the gallery is called upon to navigate the gallery space and narratives, creating one's own private pathways as one experiences the show, as one would do in an outdoor urban setting.

For Unny, this is much the same as how old mural painters used temple walls. The show offers a way, he says, "to relocate narrative art from bookish page-turning and reconnecting it to older practices of story telling".

The history of comic art and rise of the metropolis in the 1930s and 40s are intricately linked, especially in America. They served to provide cheap and affordable entertainment to a migrant population, who also used them to learn the host language. They're also famously intertwined through subject matter. For Mathen, whose stories took shape in Mumbai, urban extremities provide an impetus for new stories. "Considering," as he says, "most of the weird stuff happens in cities." This could help explain why some of the most well-known graphic novels, including Frank Miller's Sin City and Alan Moore's and David Gibbons' Watchmen and V For Vendetta, are set in grimy, film noir-esque urban locations. The works on display deal specifically with urban experiences, each with its own stylistic twists. Mathen's short stories are set in Halahala, a surreal, mythical world much like our own, and capture a twisted, dystopic urban reality. Each story is drawn in a distinct style: Dreams, and Fishing are crisp and lucidly clean while Bloody Lal and Super Heroine Help are heavily detailed. The colours in The Prey are reminiscent of Tinkle comic books.

Gopalakrishnan's stories Meanwhile, Elsewhere and Super Human Existence deal with life in the city—the former overturns the idea of 'superheroes' coming to the rescue of a damsel in distress, and the other outlines in poignant detail a day in the life of an office worker. His style is sparse, neat and often beautifully cinematic. In the gallery, their stories, as Unny says, "unfold as you stand, stare and walk on" while his own—delicate, evocative sketches of Fort Kochi—"work as in a bioscope at a village fair".

For Gopalakrishnan, who describes himself as "an active member of the alternative comics movement in India", organising this show is a step towards encouraging and creating spaces for the growth of comic art in the country. Despite the rising popularity of the genre, these three artists also wish to see the first breakthrough 'Indian graphic novel' that doesn't depend or imitate Western formats. This can be done, as Unny points out, "by merely looking around, [since] life happens in our surroundings that urbanise or refuse to, in ways very different from Europe or the United States". The early works of graphic novelists Sarnath Banerjee, Amruta Patil, Parismita Singh and George Mathen have set the tone. "We need to build on this," says Gopalakrishnan. "There is no point in being talented imitators of [Western] art."

What also links them, apart from their love of the comic art form, is a fondness of flânerie, which they see as inspiration and an escape from bending over a drawing sheet. Unny loves walking in Thiruvananthapuram— "see how the place name itself stretches like a paved walkway"—and Appupen in Chennai, Mumbai or Kolkata. Gopalakrishnan strolls in his hometown Thrissur, which "surprises him with its little stories". It is said that though the flâneur forms no specific relationship with an individual during a stroll, s/he establishes a temporary, yet deeply empathetic and intimate relationship with all that s/he sees—writing a bit of oneself into the margins of the 'text' in which one is immersed. What makes Poe's story intriguing is that, while we don't know why the protagonist is haunted by the decrepit old man, it's implied that the two men are each other's doppelganger, two sides of the same person. Flânerie, after all, is not merely about the exterior, the city streets, the swarming crowds, the specifically urban sights and sounds. It is also a search for ourselves.

The Flaneur in the City will show at Gallery Ske, Bangalore, till 30 June