As the plane with the hijackers, and the prisoners they asked for, takes off, one character tells another, “We won”. “Did we?” asks the other. “We fought,” says the first man, amending his statement. “Did we?” repeats the other.

This is one of the last scenes in Anubhav Sinha’s new Netflix series, IC 814: The Kandahar Hijack, which serves both as a nail-biting thriller and as a lesson in world history. Based on the events at the turn of the millennium that India would rather forget, it recreates the longest hijack in history and what led to it. As the plane took off from Kathmandu, Nepal; it was hijacked by five men, forced to land in Amritsar for refuelling; then it took off again, made to land in Dubai; and then finally taken to Kandahar, the only airport in Afghanistan that had night landing facilities at that point because of an opium trade.

On board were 156 passengers (one, Rupin Katyal, died in flight) and on the ground was a desperate and cornered Indian government which had the difficult task of delivering three terrorists who would go on to wreak greater havoc than they had so far. Omar Sheikh went on to finance one of the hijackers of the 9/11 attacks, and the abduction and murder of American journalist Daniel Pearl. Maulana Masood Azhar formed Jaish-e-Mohammed, which carried out the Parliament attacks in 2001, the 2016 attacks on the Indian Air Force base in Pathankot, and targeted CRPF jawans in 2019 in Pulwama. The combined death toll exceeded more than 200. Mushtaq Ahmed Zargar, founder of the militant outfit Al-Umar Mujahedeen, was the third terrorist to be released. He continues to be active in Jammu and Kashmir.

One hundred and fifty-five of the passengers returned alive, with the exception of honeymooner Katyal. So, we won. The statement in the series is made by a character based on the then head of operations, IB, and now National Security Adviser Ajit Doval, played by Manoj Pahwa. Did we? The question is raised by a character based on retired IFS officer and Afghanistan expert Vivek Katju, played by Arvind Swamy.

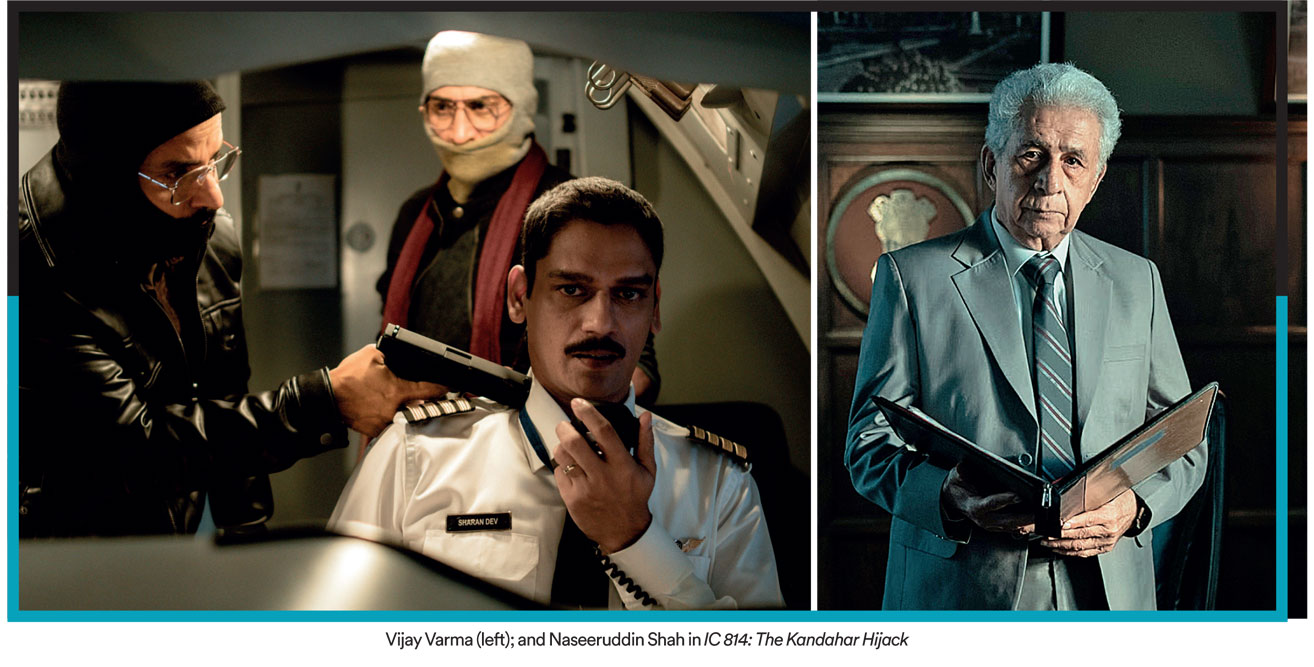

The series has a stellar cast but most names have been changed to smooth possible ruffled feathers so there is the added enjoyment in identifying the real men behind the fake names. Vijaybhan Singh, the foreign minister, played by Pankaj Kapur, is based on Jaswant Singh, the tragic hero of the story. Vinay Kaul, played by Naseeruddin Shah (and Kapur’s brother-in-law), is a composite of National Security Adviser Brajesh Mishra and Cabinet Secretary Prabhat Kumar. Kanwaljeet Singh plays Shyamal Datta, director, Intelligence Bureau, while Aditya Srivastava is AS Dulat, director, RAW. Ranjan Mishra, played by Kumud Mishra, says Sinha, was closest to the real character CD Sahay, who went on to head RAW between 2003 and 2005. Says Sinha: “We picked the essence of more than seven-eight characters and turned them into four absolutely new characters to tell the story. We were not recreating people.”

THE HIJACK IS an event that India continues to wrestle with, out of sight of its new-found profile. In his autobiography, A Call to Honour: In Service of Emergent India, Jaswant Singh writes while on the flight to Kandahar on December 31, 1999: “It is simply impossible to not jot down impressions on board this special flight. I do not really know what to term my mission— a rescue mission; an appeasement exercise; a flight to compromise or a flight to the future?”

“You must understand India was very vulnerable then. We had just done the nuclear explosion at Pokhran and incurred America’s disapproval, and we had just won the hard-fought Kargil War. We were not the world’s fifth largest economy; we did not have such warm relationships with America, France and Russia.” says journalist Srinjoy Chowdhury who co-wrote the book Flight Into Fear: The Captain’s Story, with the IC 814 pilot Devi Sharan, on which the series is primarily based. Chowdhury covered the hijack for The Statesman. It was a difficult time for him personally. His father, renowned actor Basanta Chowdhury was dying, he was writing while holding down a full-time job, and his wife was dealing with a difficult pregnancy.

Yet when the book was published, it was a disaster, recalls Chowdhury, so much so that the publisher returned the rights to him. After a few failed attempts to sell the script to Mumbai producers for a movie, the book was bought by producer Sarita Patil in 2015. Various people were attached to develop and direct it at various points, including Vishal Bhardwaj. Sinha got a call to direct it from Netflix, but he was busy. When they called again in 2022, he was on vacation in Istanbul, Turkey. They said only he could do it, so he did.

Having come off his acclaimed trilogy of films dealing with religion, caste and gender— Mulk (2018), Article 15 (2019) and Thappad (2020) as well as Anek (2022) based in the Northeast, and Bheed (2023) set during Covid-19, Sinha was ready for a bigger arc of contemporary politics. As soon as he got the 220-page script, he and co-writer Trishant Srivastava, started to examine the events beyond what was happening on the plane. And he realised, “the more you know, the less you know”.

“We used to have these meetings with Adrian Levy in Mumbai and London and I would have to stop after 20 minutes because it was too much to take in,” says Sinha. Levy, a journalist who has written several well-received books on Indian events, says he was a fan of Sinha’s work already, and had really liked Mulk and Anek. “But I was sceptical about this project initially because so many misleading versions of this event are already in the public domain. Many of these were simply rabidly Islamophobic and missed the actual story. However, Anubhav was open to ripping up what had existed and rerouting it through a different lens which explained the far larger plan that was afoot, one that had also eluded the ISI in Pakistan which was a participant in the plot,” says Levy.

As it happened, Levy had met many of the leading protagonists (on all sides, from Al Qaeda to its main operative Ilyas Kashmiri’s fighters, and from RAW to ISI) and so had researched a very different version of this story and that is what they set about working on. Says Levy: “We worked together for a year in Mumbai, London and online. I wrote, and rewrote sections—and then we pushed each other into deeper conversations about the backdrop and character motivations.” Says Sinha: “I tried to portray the office and the human being occupying it in the scenes involving the Crisis Management Group. I told the actors that I was not interested in shooting dialogue. I was more interested in shooting the other faces while one is speaking.”

It is difficult to view the exchange of terrorists for passengers from today’s perspective as so many attitudes and strategies have changed. Terror is now quite different to how we understood it back then. “Evidently the exchange was a disaster in one sense—and its repercussions are still being felt now—but saving lives was a gift that the government gave—but at what cost?” asks Levy.

And that is the broader question IC-814 asks. It foreshadows both 9/11 as well as the December 13 Parliament attack in Delhi. As Sinha says, “At one point, the hijackers threaten to crash the plane into the Parliament in Delhi. Osama bin Laden’s involvement was also clear when the hijackers and terrorists are invited to a feast when released at bin Laden’s hideout.” Several aspects of the hijacking which were known to those involved are also revealed—that the head of the Kathmandu RAW division was on the flight; that there was a bag onboard with 17 kg of explosives; and there was complete disagreement on the exchange between Union Home Minister LK Advani and Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee.

THE SERIES CAPTURES the drama inside the aircraft too, in graphic and often disturbing detail. The pilot, Devi Sharan, is portrayed as a man who puts his passengers first, and tries his best to prolong the aircraft’s stay in Amritsar where he is sure the government will execute an operation. It doesn’t happen but he doesn’t lose hope despite the hijackers pointing a gun to his neck for the duration of the hijack. “When I asked Captain Sharan about the scar, I froze,” says Vijay Varma, the actor playing Sharan, who continues to fly for Indian Airlines. Varma spent some time with Sharan on the actual aircraft, which is now used as a training aircraft and based in Jordan. Sinha says he found Sharan to be a practical man, “passionate about his work, but not overly emotional”.

Anubhav was open to ripping up what had existed and rerouting it through a different lens which explained the far larger plan that was afoot, one that had also eluded the ISI in Pakistan which was a participant in the plot,” says Adrian Levy, journalist

Share this on

Varma was among many in the cast who would hang out on the set of the Crisis Management Group, a shoot that lasted for a week, and had actors such as Kapur and Shah in full flow. Sinha shot the scenes in grey, with close-ups showing every frown, every worry line, and every dark circle. The use of the colour was deliberate given there was no black and white for the decision makers. By the time the movie reaches Kandahar, it is sepia tinted, matching the images an anxious India was treated to on its TVs. Anupam Tripathi, the Seoul-based actor who plays a RAW operative in Kathmandu who had flagged a possible hijack but was ignored by Delhi, remembers watching the scenes on his black and white TV as an 11-year-old schoolboy. “I still remember everyone asking, why can’t the passengers be brought home safely?”

Sinha captures the dynamics between the hijackers, the air hostesses, and the passengers, who just want to go home. On the ground, he touches upon the media, its cozy ties with the establishment, which prevent the whole truth from being told to the people, on the grounds of national interest. And there is a mix of actual footage of angry relatives seeking responses from the government, and re-creations, which show the extent of pressure on the government, whose first response, expressed by Prime Minister Vajpayee was emphatic: “My government will not bend before such terror.” Sinha doesn’t show Vajpayee at all, seamlessly skipping over his direct role in the exchange.

Having delivered a nuanced series that captures the human cost of the hijacking as well as the geopolitical implications, Sinha now wants to go bigger. “I am inspired by Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. I quite like the idea of the Trojan Horse movie,” he says, referring to a movie that informs while it entertains. “I want to make cinema that is popular in its ambition, and still has a voice that matters,” he says.

About The Author

Kaveree Bamzai is an author and a contributing writer with Open

More Columns

The lament of a blue-suited social media platform Chindu Sreedharan

Pixxel launches India’s first private commercial satellite constellation V Shoba

What does the launch of a new political party with radical background mean for Punjab? Rahul Pandita