Play It Again

Hours before his death, sarode maestro Ustad Ali Akbar Khan couldn't resist giving his last music lessons

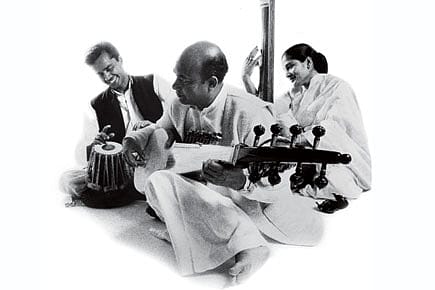

The gathering at a memorial service in San Rafael, near San Francisco, on 21 June was testimony to a great man passing. "One of the world's greatest musicians", in fact, as violinist Yehudi Menuhin had once described his friend, Ustad Al Akbar Khan. The sarode maestro passed away after a long illness on 18 June, at the age of 87.

Recognised as one of the foremost proponents of the sarode (meaning beautiful sound in Persian), a 25-string instrument, Khan actually played on the Maihar prototype, which his father, Ustad Allaudin Khan, had developed by improving on the conventional sarode.

Though Khan was on dialysis for the past several years, he had ceaseless energy as a music mentor. Till a fortnight ago, he was taking classes at his school, the Ali Akbar College of Music in San Rafael. When his health deteriorated, he taught from his bedside. And, hours before he breathed his last, he asked his family to play for him and gave them musical instructions one last time. Such was his love, dedication and desire to listen to and teach music. "Music is the real food for your soul, and it was created by God," he is known to have oft repeated.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Khan had tirelessly promoted Indian classical music in the West since the 1950s. A prolific composer, he also released about 95 records and scored music for several films, including Bertolucci's The Little Buddha, Merchant-Ivory's The Householder and Chetan Anand's Aandhiyan. He was also nominated for a Grammy more than once. "He brought this music to the West and spread its seeds to thousands and millions of people," said Mickey Hart, drummer for The Grateful Dead, and his student in the late 1960s, at the memorial.

Also among the hundreds of people present were Anoushka Shankar, Ustad Zakir Hussain, alto saxophonist John Handy and sitarist Roop Verma. Anoushka mentioned that she'd never seen her father, Pandit Ravi Shankar, so shaken as when he heard of Khan's death.

Born in East Bengal in 1922 to Allauddin and Madina Khan, he began his talim (training) at the age of four. His father was court musician to the Maharaja of Maihar in Madhya Pradesh and founded the Seenia Beenkar Gharana. Khan made his musical debut at the age of 13 at Allahabad. Behind that debut were relentless practice sessions, usually lasting 18 hours each day. His father was a strict teacher, and they would do riyaz at 4 each morning. Khan once told this correspondent, " 'Ali Akbar!' my father would call out in the morning. I always had the sarode in hand. When he called the first time, I'd be out of the room. By the second call, I'd be near his living room and by his third, I'd be by his side."

In 1943, when he was 21, Khan became the court musician for the Maharaja of Jodhpur. After the ruler's untimely death, in 1948, he moved to Bombay. This paved the path to his foray into the film industry—much to his father's disapproval, who called him a "tajya putra" and disowned him for a while. His father eventually came around when he saw one of the films based on a Tagore story. "I wanted to bring music to the street, to the rickshawalla and tangawalla. That was the only way they could listen to it," Khan said.

More than anything else, Khan wanted to teach. In 1957, he opened the Ali Akbar College of Music in Calcutta. It didn't run long due to lack of funds. In 1967, he established the college in San Rafael, which emerged as a magnet for musicians from across the world. The school expanded to have local branches in San Francisco Bay and one in Switzerland. "I didn't get any help with the college [in Calcutta]. But here in the US, I have had 10,000 students come to this college alone," he'd said. What he could not do in India, he was able to achieve in the US. And that is the irony of his story.

Kamla Bhatt is the host of an online radio show, The Kamla Show