Painting the Self

IN 2021, ZAAM ARIF, a Pakistani American artist based in Houston, Texas, got a call from The New Yorker. The magazine was preparing to publish another Pakistani American, the writer Daniyal Mueenuddin, who shot into the literary firmament with his highly acclaimed debut collection of stories, In Other Rooms, Other Wonders, in 2009. Then, like a passing comet, Mueenuddin had all but disappeared from the public eye. And now, a decade later, he was ready to emerge from his hibernation with a brand-new novella called Muscle, scheduled to appear in the prestigious magazine. The New Yorker wanted Arif to read and respond to the story through his art.

"I wasn't familiar with Mueenuddin's work at the time," Arif, 25, says on a video call from his studio in the US. "But as I went through Muscle, I saw so much of myself in it." As he read on, Arif began to make a few sketches on the side, based on his initial reactions. The New Yorker loved these roughs and commissioned him to illustrate the story.

For the next month Arif, who usually has his nose in multiple books at any time, read and re-read Mueenuddin's novella, trying to get the essence of it. "I was focusing on the words and sentences, their meaning and intent, reading between the lines" he says. In a few weeks, he had created a set of stunning paintings, eventually printed with the story.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

And so, all of 22 years old, Arif became the youngest Pakistani artist to be published by The New Yorker. Since then, he has shown his work around the world— in India, Pakistan, Italy, the UK, and the US. Currently, his solo exhibition, Waking Dream, is on in Delhi.

Intense and densely allusive, Arif's work is a rare confluence of the cerebral and the visual. His imagination is reinforced with literature, philosophy, cinema, and psychology. You sense a melting pot of influences and affinities coursing through his canvases, the promise of a sensibility shaped by unusual choices and life experiences.

Arif's reaction to the emotional core of Muscle isn't surprising. The protagonist of the novella is a young man like him called Sohel, except Sohel is the scion of a powerful feudal family in Punjab in Pakistan. Sohel is instantly recognisable as one of Mueenuddin's creations, men who are caught between the crossfire of traditional and modern values. After a liberal education in the US, Sohel returns home with dreams to reform the ancient, exploitative system of fiefdom. With his father and grandfather both gone, he must take charge of the family estate, but he doesn't want to perpetuate the reign of terror of his ancestors. Instead, he believes "humane interventions" will bring about peace and order to the Badlands.

Alas, Sohel's noble mission is misconstrued as a sign of weakness by his subjects, leading to darkly comical moments. His language of civility and compassion falls on deaf ears as the villagers brazenly overreach their rights. For generations, these rustic folks have only been kicked, cursed, and sworn at, ruled by the trigger of the gun rather than kind words. And so, they find their foreign-returned young master naïve and risible.

In Arif's paintings, we sense the despair, confusion, and bathos of Sohel's life. The scenes he paints are saturated with burnt umber and burnt sienna, which are among a limited palette of five-six dark colours he favours. If the villagers appear as shadowy forms, with a hint of menace, sitting in open courtyards, the genteel interiors of Sohel's home exudes a false sense of security. The fire crackles in the cosy living room, drinks are prepared on the side, stacks of books lie neatly arranged on the shelves. But the inheritor of these luxuries looks desolate, wasted by worry, and unable to reconcile his lofty ideals with the brutal reality of everyday life.

Arif conveys the tussle between Sohel's inner and outer worlds through a sharp and sustained juxtaposition of the warm colours of the indoors with the frenetic brushstrokes of the big bad world out there. His empathy for Sohel, perhaps born out of a sense of affinity, becomes palpable. Both these young men are insider-outsiders, fated to live on the cusp of cultures, struggling to gain a foothold in two contrasting worlds, and forever condemned to remain liminal observers.

Zaam Arif was born in Karachi in 1999 to artists AQ Arif and Mussarat Arif, but brought up, for the most part, in the US. Like many children, he didn't want to follow the footsteps of his parents. "Early on, I decided I wanted to be a scientist, so I studied physics," he says. "But since childhood, I was surrounded by art at home, made by my parents and others."

When it dawned on him that physics wasn't his real calling, Arif moved on, by turn, to writing, music, photography, even filmmaking. "Every part of the arts except for painting," he says with a laugh. Then, one day, he saw a masterpiece that changed his mind.

It was Pablo Picasso's Guernica (1937), the Spanish artist's grand vision of the pity of war, that first made Arif aware of the endless possibilities of painting.

A few days later, on a rainy evening, he climbed down to his father's studio in the basement of their Houston home. His dad was out, and Arif had no idea about art making. "So, I picked up a sheet of paper and began painting shapes with acrylic," he says. Later, when Arif Senior saw his son's handiwork, he was impressed, and encouraged him to try oil.

Soon enough, the young man, who had until recently wanted nothing to do with art, was painting abstract "Picassoesque shapes" every day, eventually graduating to figurative painting and portraiture, inspired by master artists like Colin David of Pakistan, Matthew Krishanu from Britain, and others he had admired through his growing years.

For Arif, who isn't formally trained in art, abstraction always signified something mysterious, a work that didn't yield its meaning easily. "But soon I realised there are many elements in figurative art, too—in the works of Francis Bacon or Peter Doig, for instance—that are no less cryptic," he says.

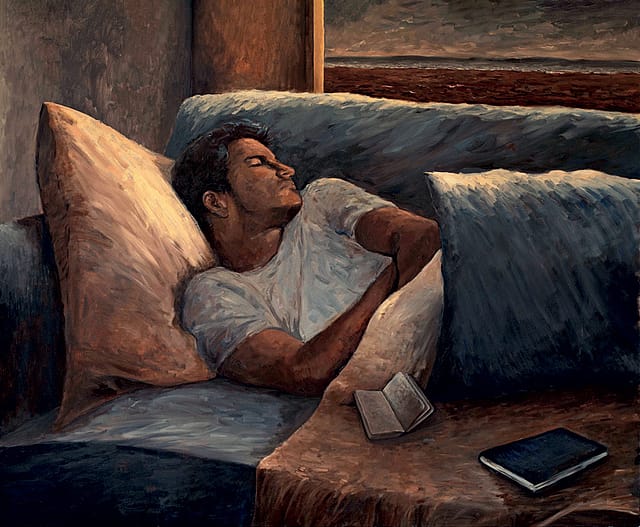

In A Crisis in Summer (2023), and the studies he made for it, Arif seems to uphold the inscrutability of the human form in the figure of a man lying on a couch with his eyes closed. It's impossible to tell if he is resting, lost in thought, sleep, or pain. A couple of notebooks lie next to him, one of which may have been flung in irritation. Above him is a window (or is it a painting?) through which one glimpses a beach, further deepening the mystery of meaning.

"I wanted to convey the feeling that's aroused by a work of abstract art, say, by Mark Rothko, by using the language of figurative painting," Arif says. "I feel I can go on exploring the figure for the next 1,000 years and still not be able to say what I want to." Rothko, as Arif puts it, had taken out every distraction from his art. "Looking at his paintings is like looking into a mirror. I want my art to have a similar effect on viewers. I want anyone from anywhere in the world to be able to connect with it."

Every artist strives to make their work universally appealing, but for artists from South Asia, such aspirations have always been an uphill battle, especially in the West. As art goes global, artists from Asia, ironically, increasingly find themselves pigeonholed by their race, histories, and ethnicity. So, despite their immense gift, painters like Arif, or his compatriot, the hugely talented painter Salman Toor, can seldom escape the epithet "Pakistani" from being affixed to their artistic identity.

"I try to stay away from making my art about one thing only," Arif says. "I don't like to tell people the full story behind my paintings. I want them to find themselves in my work."

AS YOU STAND IN front of the canvases, some of which feel towering, figures and forms loom over you. But there's more than materiality to what you witness. Looking at the solitary woman seated on her bed in Exile (2023), you feel a pang of recognition (Is she melancholy? Sleepless? Haunted by night terrors?) rather than any obvious desire to make narrative sense of the scene. The composition echoes Edward Hopper's Morning Sun (1952), which, like all of Hopper's paintings of men and women, depicts a state of mind, rather than specific people or places.

In Arif's work, the most ubiquitous figure is that of a young man, caught in moments of rest and reflection ("I thought the world did not need another male artist to be painting women," he said in another interview). It is as much a self-portrait as a distillation of the characters and experiences he has drawn from some of his favourite books and movies by Nikolai Gogol, Franz Kafka, Ingmar Bergman and, of course, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who he first read during a particularly dark period of his life.

"I was deeply moved by Raskolnikov's dilemma between ethics and morality in Crime and Punishment," Arif says. "Dostoyevsky was probably among the first psychologists. He explored the self like few of his contemporaries did. In my work, too, I try to understand myself through the figures I create—be it through self-portraiture or by painting others."

Contrary to becoming solipsistic, this process of self-analysis through art expands the consciousness, it provokes the artist to ask the Big Questions of life and death, faith and the absence of it. In the cinema of Guru Dutt, for instance, Arif senses a version of this lifelong search for meaning, playing out in different plotlines. "Like Bergman and Tarkovsky, Dutt was exploring the question of what it means to be an artist in his time," he says.

As we close our conversation, Arif mentions his growing awareness of the greats that are part of his personal heritage, artists and writers from the subcontinent he hasn't paid close heed to so far. We speak of the genius of Saadat Hasan Manto, specifically about 'The Dog of Tithwal', a tale of mindless violence spurred by Partition. "Sometimes I feel like that simple dog, unable to make sense of a world that's changing faster than he can keep up with," Arif says.

And yet, from the moment you encounter this 25-year-old's work, you know you're in the presence of an artist who's special, one among a handful of chosen ones to help us see the world through more humane eyes.

(Waking Dream by Zaam Arif is on display at Vadehra Art Gallery, Delhi, till March 1)