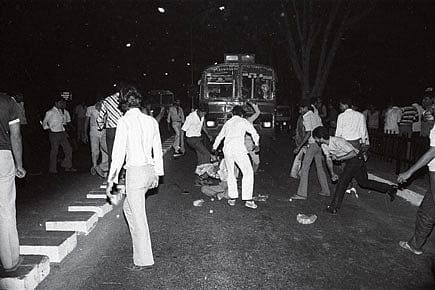

Never Forget

A travelling exhibition on the horrific anti-Sikh riots of 1984

The first indication I had that something was horribly wrong in Delhi after Indira Gandhi's assassination was when I saw an elderly Sikh on the Defence Colony flyover with his turban unwound and trailing on the ground. I was in an auto and as I reached the top of the flyover, I saw wisps of black smoke rising from different parts of south Delhi. It was the day after her killing, and by that evening, news had gone round that violence had erupted across the city. The information network then was of landline telephones, and people were calling friends about the panic spreading area by area. Friends in the press had more information than the general public, and my flat in Civil Lines became a dormitory for stranded press friends from outside Delhi. The photographer Raghubir Singh arrived late at night from Shimla, and we had to scramble to collect enough food for all as everything was shutting down. A wild rumour was spread that Delhi's water supply had been poisoned.

In the next few days, as the extent of the violence became clear, I joined a group of friends in a spontaneous relief effort. There were many citizen initiatives which had come up to provide relief to the victims, and ours was just a small effort. Patwant Singh, Leila Kabir Fernandes, Pramila Dandawate and others had somehow come together in two Ambassador cars and we drove across the Yamuna to Kalyanpuri with blankets, medicines and food supplies, not knowing what we would find.

What we did find shocked us deeply. I had two rolls of Tri-X film and my Pentax, and realised right away that I had to document what we saw. Only two adult males were left alive in this one gali in Sector 13, where 22 had been burnt alive. No help had reached these people, who were wandering stunned in the shells of their burnt-out homes, showing us the burnt autos their menfolk used to drive to earn a living. I noted down Gagan Singh's name when I photographed his widow holding his finger, chopped off to steal his gold ring. That photograph was prominently displayed on the truck that carried a travelling exhibition over the last two weeks in its journey from Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar to Delhi. Justice Phoolka, who has been fighting for justice for the victims for the last 28 years, identified her as Nanki Kaur. Twenty-eight years later, I know her name.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

My parents had told me of the Great Killings in Calcutta in 1946 when my father took his young bride back to his home. They drove in a tonga through streets strewn with dead bodies being eaten by vultures. My mother, pregnant with my sister, never forgot those days, and it was one reason I was given the name I have. I never thought I would see anything similar in my lifetime, but how wrong I was. After 1984, there was Ayodhya and then Gujarat. My camera has sought to document in each of those events too.

My pictures of that afternoon in 1984 were published in The Deccan Herald and The Herald Review, for which I was then working as a graphic designer. The Illustrated Weekly of India, too, published them in large spreads. Many were used in the PUCL/PUDR report on the Delhi killings, where all the photos were printed anonymously. This was because there was a fear that any witnesses, and photographers in particular, would be threatened, intimidated or attacked for publishing evidence. In fact, it is very hard to find images of the 1984 violence now. My negatives were safely processed by Mahatta's and I made sure the multiple sets of prints they made went to different cities and into different newspaper archives.

This fear was a harbinger of what happened in Ayodhya in 1992, when at a signal, all photographers at the site were systematically attacked so they could capture no evidence of the Babri Masjid demolition and the people involved.

Seeing these images again, along with those by other photographers, outside the Bangla Saheb Gurdwara in Delhi, raises mixed emotions. While they constitute material evidence of the massacres, there has barely been any justice for the people who suffered.

As an individual, one feels helpless. The only hope is that these images of Delhi 1984 will not let the injustice and horror be lost in the past and they will serve to keep the memory alive until there is justice for not just those who suffered, but for all of us. For I believe a society without justice is doomed.