Leaving a Footprint

A stepchild of the art world, printmaking has lately been in the spotlight

A stepchild of the art world, printmaking has lately been in the spotlight

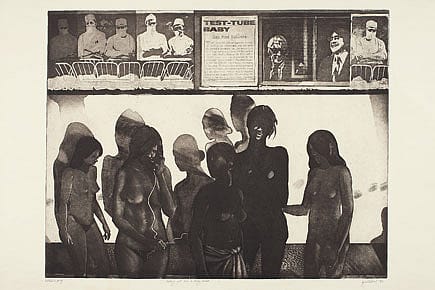

When you look at Zarina Hashmi's minimalist prints, you will not see the artist's gnarled and bony hands, which slaved for years chiselling away at unyielding wood to create her woodcuts. When you look at Anupam Sud or Laxma Gaud's fine figurative etchings, you will not experience the nauseating ef-fect of the acid fumes that they inhaled in their studios. The hours spent grind-ing a lithography stone into submission cannot be captured when you view the luscious inky black lines of Sunil Das or Surendran Nair's lithography. It is a therapeutic, often mad, drive that compels these artists to create these reproducible prints, a drive that many viewers and collectors will never fully understand.

If you are around the picturesque but slightly crowded Hauz Khas Village and have a few hours on hand, step back in time with a well-researched show at the Delhi Art Gallery, The Printed Picture. This puts the stepchild of the art world, printmaking, back in the spotlight.

The show explores the creative compulsions of artists who use these out-dated labour-intensive processes. As the 72-year-old Gaud, known for his sexually-charged etchings, paintings and sculptures, had once declared, "I am not satisfied until I have duelled long hours with a copper plate to achieve the desired results."

The Delhi-based Sud, 68, whose works have feminist overtones, too, says, "Unlike painting, etching is an indirect process that requires a lot of hard labour. But its linear qualities and grey tones complement my work; drawing with a hard point on a hard surface gives me great gratifacation."

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

However, the economics of pro-ducing prints and the heavy techni-cal backing needed to create them has made it one of the most severely threatened mediums of our times. Worse, col-lectors have been reluctant to place prints on the same pedestal as a painting or sculpture. The fact that they can be reproduced, they feel, lowers both their snob and resale value.

But if Paula Sengupta, curator of The Printed Picture, is to be believed, there has been a change in the approach of younger printmakers. "Artists, like Archana Hande and Ravi Kashi, are not treating prints as individual editions, but are combining printmaking techniques with painting and installation art," says Sengupta. There will always be purists, she admits, but edition printing does not make sense anymore and the rigidity around the process is slowly disappearing.

In fact, says Kishore Singh, director of Delhi Art Gallery, there have been a lot of first-time buyers for The Printed Picture, "given that the artworks are very affordable, the exhibition is well documented and the referencing and documentation is complete". The show includes Pradip Bothra's collection of 18th and 19th century European prints as well as modern masters like Krishna Reddy and Sakti Burman. A collector's dream is the historically important hand-tinted intaglio by Robert Ker Porter titled The Glorious Conquest of Seringapatnam (1803), capturing an era before photography.

Delhi Art Gallery is not the only one to bring the focus back on prints. We recently saw a rare collection of Kalighat pat prints at the National Gallery of Modern Art. The collaborative exhibition of the V&A Museum, London, and the NGMA had rare gems like the Tarakeshwar Affair suite of paintings on the scandalous love triangle of Mahant, the delectable Elokeshi and her unfortunate husband.

In May, the Lalit Kala Akademi's Rabindra Bhavan played host to an exhibition of contemporary Polish printmaking, drawing attention to the commonalities with the socio-political struggles that informed printmakers like Somnath Hore and Chittaprosad during India's struggle for Independence. And Gallery Ganesha is currently hosting 25-year-old Dushyant Patel's solo of etchings. "To create a sustainable market for prints, we target the budget collector who has a few thousand to spend on art, not crores," says Dinesh Vazirani, Director of Saffronart.com, which recently held a sold-out auction of 110 prints that mixed photography and prints by artists like Atul Dodiya and Aprita Singh.

Artist collectives too are doing their bit by providing those who want to continue with printmaking (but do not have the technical back-up) with materials and machines, hot cups of tea and loads of camaraderie. These include Garhi Studio in Delhi, set up by the Kendra Lalit Kala Akademi in 1976 under the leadership of the late Sankho Chaudhury, Chhaap in Baroda and the Kanoria Printmaking Studio in Ahmedabad.

"However, we still face a lot of resistance from galleries who are not very keen to showcase printmaking on a serious note," says Rajan Fulari, who currently heads the Garhi Studio. Perhaps reinventing the process is the only answer in today's quick-fix world.