In Search of Tagore

Photographer Edward Hoppé came to India on Rabindranath Tagore's invitation. Yet, it is Tagore who seems the most elusive in his photographs

'In true portraiture no mere trappings can help in interpreting individuality. To confirm the spirit behind the eyes is the test,' wrote Emil Otto Hoppé in his autobiography, One Hundred Thousand Exposures, in 1945.

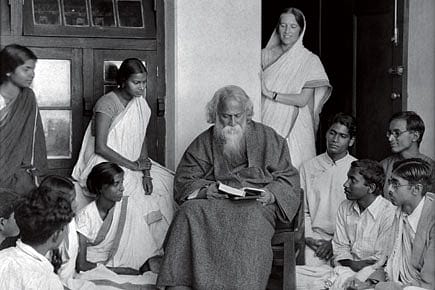

Hoppé, the German-born British photographer who took photographs for more than six decades till the late 1960s, is remembered for his portraits of persons and countries alike. Apart from capturing stalwarts like Thomas Hardy, George Bernard Shaw, TS Eliot and Albert Einstein, he also visited Santiniketan in 1929, on an invitation from Rabindranath Tagore.

Hoppé is one of the rare Western photographers to visit India in the early 20th century, a time when the aftermath of WWI and the Indian freedom struggle kept foreigners from visiting the country. In all, the photographer took more than 3,000 photographs in India. A selection of them taken in Santiniketan and Mumbai is currently being exhibited at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS) in Mumbai, to commemorate the 150th Birth Anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore.

In one of his unpublished essays titled 'A Poet's School', Hoppé describes Santiniketan. 'Some hundred miles from Calcutta is a university which is unique, totally unlike any other in the world; the tangible evidence of a poets vision, and yet so practical in its application that its name bids fair to be as familiar to posterity as those of Oxford and Cambridge, the Sorbonne and Harvard are to people of today.'

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Hoppé was clearly inspired by the school, and ended the essay with the need for such a place: 'a world whose guiding spirit is personal love…where life is not merely meditative but fully awake in its activities.'

His photographs capture Santiniketan in all its diversity—ranging from foreign students, visiting dignitaries to agriculture classes and the rustic Bengali landscape. "In Hoppé's photographs," says Sabyasachi Mukherjee, director of CSMVS and originally from Bolpur, Santiniketan, "I can see the actual Santiniketan. The barren land, the vast sky, the prayer meetings. Today, the place has changed so much that one can't recognise it as the place these photographs were taken in."

When it comes to Mumbai, though, the city in Hoppé's photographs is an instantly recognisable one. The spirit of Mumbai as a fast-paced metropolis is evident even in 1929, even in sepia tones and vintage clothes. People loitering at Oval Maidan to watch cricket matches, falling out of public transport buses, conducting worried discussions with lawyers, and so on.

The two are in sharp contrast. Santiniketan is a poet's vision, in harmony with nature, bringing together Eastern and Western cultural influences. Mumbai, on the other hand, is an emerging cosmopolitan city where the impeccably dressed British travel in cars while the locals use the pavement and buses.

What remains most elusive in the exhibition is Tagore himself. While Hoppé's photographs do justice to the poet's vision, one wonders if they succeed in doing the same to the poet behind the vision, and the man behind the poet. You see Tagore dictating notes to his secretary, seated on his chair. You also see Tagore with his granddaughter, once again, seated on his chair, while she sits by his feet. Tagore is at the centre of Hoppé's photographs of Santiniketan. Yet, his relationship with the rest of the photo's composition is unclear. To confirm the spirit behind the eyes is the test of a portrait, says Hoppé. In these photographs, Tagore's eyes mostly evade the camera, giving the poet a stature and aura that perhaps lie beyond our comprehension.