Himalayan Leap of Love

A Sino-Tibetan love story, welcomed and cherished by an Indian hillstation

Gyalo Thondup not know the precise moment that love happened to him; he just happened to realise, by and by, that his heart felt warm and aglow. And that it had to do with his journey of love from the historic city of Nanking in China to the Himalayan town of Darjeeling in India.

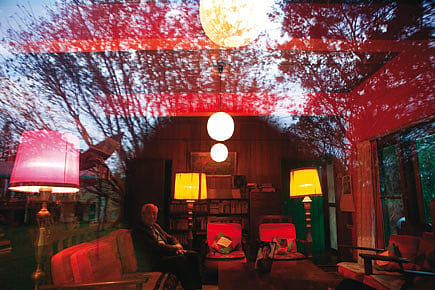

It seems like a fairytale now, as we look back at events from Thondup's cottage nestled in the natural beauty of an estate off 8th Mile Road in Kalimpong, near Darjeeling in West Bengal. Sepia photographs perched on his living room mantle take us straight back to the beginning—in 1945.

Gyalo's country of origin, Tibet, was experiencing a measure of peace, back then, having reasserted independence in 1913 after decades of rebuffing British and Chinese attempts at taking control. His fellow Tibetans were suspicious of Chinese intentions, but were hopeful all the same of peace talks with the Chinese Nationalist Party, Kuomintang (KMT). It would not be until 1949 that the Communist regime of the People's Republic of China, under Mao Zedong, would stake its claim to Tibet.

It was a period of calm, and young Gyalo took this chance to leave home for Nanking in pursuit of higher studies. A close grasp of the Chinese language, his father believed, would equip him well to participate in the expected talks. This was important to the future of Tibet, and that of Gyalo's younger brother, Lhamo Thondup, who had been recognised as the 14th Dalai Lama only eight years earlier. It was while mulling all this at the Central Political University of Nanking that he first met her. Di Kyi Dolkar. A pretty young girl with a beautiful smile.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

"I first got to know her brother, a navy officer who introduced me to the family. Her father was a very important general in the Nationalist government," says Gyalo, now 82, trying hard to keep the lines of age on his wizened face from betraying a blush. "It's not important enough," Gyalo suddenly says, buying himself time to regain an air of unexcitable seniority. But it is, we insist, and this time, he lets himself go. "She was highly educated. She was already a graduate when I met her and was working at the Baptist Mission Hospital…" His eyes soften and voice swells as he talks about her.

After a brief courtship, the two got married in Nanking. It was 1949. He was 19, and Di Kyi, 21. Not only was she an older woman, scandalously so for the 1940s, but also a Chinese citizen. "If one came to know of a Tibetan marrying a Chinese now, it could be a huge issue," he says, "Even back then, a few eyebrows were raised, but then Tibetan people are very broadminded and moderate. Our marriage in itself wasn't much of an issue."

But a rude shock lay in store. The very same year, the Communist Party assumed power in Beijing, and all of a sudden, the couple found the going tough. Anger in Tibet over China's new bullying attitude made it difficult for Gyalo to return to his homeland with his newly wed Di Kyi. Nor was it easy staying aloof of Sino-Tibetan tensions in Nanking.

In search of refuge, the couple made their way by land—partly on horseback—to the Indian border and reached the town of Kalimpong. Over the next two years, Di Kyi set up home here while her husband made trips to Taiwan, the US and other places. "She would accompany me often during my travels," he says, "But when she got pregnant, I urged her to stay back."

Life here was a relief. But what Di Kyi least expected was to have the Tibetan crisis land right at her doorstep. In 1959, the Dalai Lama's fabled escape with swarms of followers from Lhasa to the hills of Darjeeling presented her a challenge: helping refugees. "On days, there would be hundreds of them standing outside our house," says Khedroob, the eldest son of the couple. "I was in Delhi a lot between 1959 and 1999," adds Gyalo, "I would also visit Beijing often, carrying messages to the Communist government from the Dalai Lama. Di Kyi was a huge support to me."

With Gyalo busy playing liaison man between Tibet and India, his wife got into the act. In 1959, with Rs 700 raised during a charity football match at St Joseph's School, she started India's first ever Tibetan Refugees Self Help Centre. The idea was to help the adults pick up vocational skills so that they could fend for themselves, even as the children were given free food and education. "What started with four workers and two rooms has now expanded in scope and size," says Dorjee Tsetsen, manager of the centre, "Between 1965 and 2000, we had nearly 650 members here. Mrs Thondup even sent some children to Japan and the US to study."

The staff at the centre remembers her as an extremely gentle and spiritual person. "She made this place possible," says Jampa Tenzin, a staff member, thankful for her vision and foresight that made it easy for them to run the centre even after her death in 1987 of pancreatic cancer. "My mother was a very efficient woman," says Khedroob, "She accomplished so much, but quietly. It was only when I grew up that I realised the significance of her work. She managed the family as well as the centre beautifully. My grandmother really warmed up to her because of these qualities."

Darjeeling's townsfolk vividly remember the crowds that turned out to pay their homage on her death, so many lives had she touched. "I was always sick as a child and couldn't do much manual work. So she encouraged me to learn how to dye, and thanks to her I found my vocation," says Tenzin, who was visited last year by a 98-year-old man from California who had bought a carpet from him a decade ago. "He told me that his house had burnt down. And he ran into the fire simply to save his two cats and that carpet. I was so touched." It was a craft he'd learnt thanks to Di Kyi.

Gyalo, shaken by her death to his very core, took a long time recovering. "She was the pillar of this family," he says, "It all happened so quickly. I have always felt that I was blessed to have two very great ladies in my life. One was my mother, who encouraged me in my work and sent me money from Tibet, which was a very dangerous thing to do at the time. And the other was my wife, who was the very backbone of my existence."

As we look around the house, he shows us the trees they had planted together and the noodle factory they had set up together on the estate. Her memories, it's clear from his expression, help sustain his spirits as he goes about leading a life of retired quietude in Kalimpong. The refugee centre is now managed by Khedroob, while his younger son works as a doctor in Hong Kong.

There is an air of relaxed calmness about him, the air of a man who has the satisfaction of having had true love by his side. It really doesn't matter that he cannot pinpoint the exact moment when he realised he was in love. "When I met her, I knew she was the one for me. It is karma [destiny]. How else would I go a thousand miles away from Tibet to Nanking and meet her? Why else would she follow me to a country which she had never visited before? You can't explain these things," he says, heaving a gentle sigh, "But I would like to believe that all this was an arrangement from a previous life."