Ganesh Haloi: Finding Colour Fields

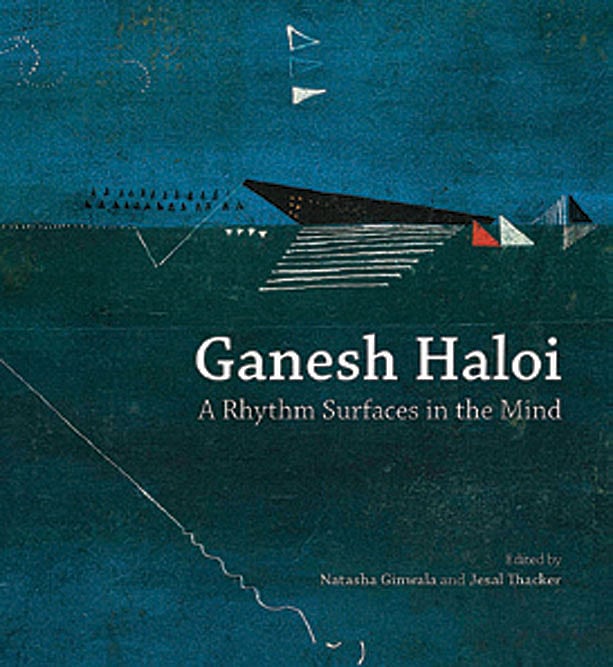

AS THE MIC IS handed over to Ganesh Haloi after the experts have had their say at a book launch held in Mumbai recently, he smiles shyly and mutters something on the lines of, “I am not a speaker,” before quickly slipping away to exchange pleasantries and sign books for what seems like a wide circle of friends and the fraternity. But once out of the public eye and back in the privacy of his hotel room, he is much more at ease talking about his life and art and how the two are intertwined inextricably. At 86, Haloi is the subject of Re-citing Land, a new career-spanning retrospective guest-curated by Roobina Karode at the Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation (JNAF) gallery in Mumbai. Presented in collaboration with Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, JNAF and the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA), the exhibition looks back at six decades of his practice. To mark the occasion, Akar Prakar gallery and Mapin Publishing have also released a monograph titled A Rhythm Surfaces in the Mind (256 pages; ₹2,500), edited by Natasha Ginwala and Jesal Thacker, to foster a better understanding of Haloi and his magnetic abstractions.

“I don’t know how I became a well-known artist,” the octogenarian says, in a self-deprecatory aside, shortly after I introduce myself for this interview. Haloi is an unmistakably abstract painter, whose enigmatic dreamscapes evoke the musicality of Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky and pulsate to the sound of nature derived largely from his childhood imagination. Though he welcomes my suggestion that there is an aura of mystique and ambiguity in abstraction, he categorically rebuffs any attempt to be labelled as an abstractionist. “In both life and art, there’s seen and unseen, known and unknown, present and absent and visible and invisible,” he says, explaining, “Through my paintings, I want to express my inner self, which is not available for the world to see. You might feel my art has no form and movement because your eyes are trained to detect recognised narratives while I am suggesting, ‘Just look. Feel. Do not always try to make sense of the world.’ If I tell you to look at a flower, what will you do? In trying to define it you will forget to experience it.”

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

As an artist, Haloi seems to inevitably gravitate towards capturing the hidden energies and subliminal impulses intrinsic to the human psyche. Despite his paintings often appearing strikingly meditative, he refuses to concede that they have anything to do with solitude, silence or melancholy. “In fact, they are playful,” he insists. “There’s a continuous flow of what in Sanskrit we call ‘lila’. You can see cosmic drama and rhythmic harmony taking place on a grand scale. I don’t think my paintings are pensive at all.”

HALOI’S TECHNIQUE AND style reflect his meticulous awareness of the miniaturist tradition. Each painting for him “is both a discovery and a struggle,” reckons Roobina Karode in her essay in A Rhythm Surfaces in the Mind. Unlike some of his contemporaries across the subcontinent, Haloi has “steered clear of Western influences,” adds Reena Lath of Akar Prakar gallery. His preferred medium for over two decades has been gouache on Nepali paper, which has been critically interpreted as a nod to the Santiniketan greats like Nandalal Bose and Benode Behari Mukherjee who advocated homegrown solutions in their effort to usher in modern art in India. Haloi, who lives in Salt Lake, Kolkata (his exhibition is currently also showing at Akar Prakar gallery in his hometown), admits that he wants his paintings to have an earthy touch. “I like working on Nepali paper. It is widely available in Bengal. The paper has a certain texture and fibre, which holds the colour and lets it glow without becoming garish. I think it very much suits my temperament as an artist.”

As you spend more time in Haloi’s “colour fields” — as some academics and critics have dubbed his abstractions — you realise that he might be subconsciously mapping the land. Objects in his work seem to be suspended between the ground and horizon, sky and water, as if there’s a lost landscape somewhere underneath the abstract surface. Often, geometric patterns and gently undulating shapes create a visual tension. “Nothing in my painting is static. Everything is moving and is in perfect rhythm,” he says, reasoning that the universe itself is in constant motion. “Look around and you will see that everything is moving. The sun and earth are rotating. Trees are swaying. The water is shifting. Clouds are never in one place. Every single thing has a flow and balance and we are all working in relation to each other.”

Re-citing Land is a complete recap of the artist’s oeuvre. Every milestone of value to him has been chronicled. As you walk around the gallery, a constellation of smaller details and nuances gradually lead you to the bigger picture. All the creative hard work and slow-burn progress from his apprentice years to maturity remind us of the phrase, ‘Rome was not built in a day’ — except in Haloi’s case, we might be better served if we replace Rome with Ajanta. “Earlier, you mentioned Paul Klee and Nandalal Bose but I can tell you that nothing has influenced me more than Ajanta murals,” he says, of the formative years he spent working at Ajanta Caves in the Aurangabad district for the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) following his graduation from Government College of Art & Craft, Kolkata in 1956.

Dating from the 2nd century BCE and 1st century CE, the rock-cut art of Ajanta remains, according to him, “the highest peak of human creativity in Indian civilisation.” His job at the ASI was to make faithful copies of the paintings and sculptures that abound in the historic Buddhist cavern. A Rhythm Surfaces in the Mind is studded with several watercolours and sketches from this period providing a glimpse into Haloi’s artistic development. He tells us that when he first laid his eyes on Ajanta art he was bedazzled by their unique composition, gestures, lines, colours and the technical virtuosity displayed by the painters and craftsmen of the time. “I stayed there for seven years. In a way, I was cut off from the world. It was an intense phase of my life. I was totally committed to my work. The only thing I had with me was an omnibus edition of Rabindranath Tagore and sometimes, I would get copies of Anandabazar Patrika,” he says. Ajanta paintings are inspired by the Jataka tales, chronicling Gautam Buddha’s early life. “The fables and parables about Buddha’s struggles and sacrifices create an environment of divinity. The scenes are arranged in such a way that artists even today cannot achieve that with all the modern technologies at their disposal. For example, I was struck by the painting of an elephant. The artist had painted only the elephant’s head and no other body parts. But it was done so powerfully that by just looking at the elephant head you feel that the animal’s back portion is also there. Actually, it’s not there. It’s an illusion.” In awe of Ajanta’s sacred beauty, he remembers telling his superintendent, “Sir, these caves are sheer treasures. We must put gun-toting guards outside to protect the site.” For him, the lessons learnt at Ajanta caves were both spiritual and material. “That is the very reason why I flourished as an artist,” says Haloi, who also made a trip to Bodh Gaya subsequently to feed his curiosity about Buddhist philosophy.

THE OTHER RECURRING motif in his art has always been his idyllic childhood. He talks animatedly about growing up in undivided rural Bengal. The dreamlike quality of his immediate surroundings have found vivid expression in his paintings over the decades. Born in Jamalpur in 1936, now in Bangladesh, Haloi’s home was near the river Brahmaputra — a memory that brings a nostalgic smile to his face. “Childhood is a continuity that lives inside you even when you get as old as I am. Probably, my paintings still have a connection somewhere with my life in Jamalpur.” Any conversation with Haloi always circles back to what he calls the “pain of departure”. By that, he simply means that his family was uprooted from their blissful life in Jamalpur due to religious persecution. For him, home, it seems, was also where the hurt was. Those were turbulent times for Hindu communities living in Bangladesh. Forced to flee their home, Haloi’s family ended up in refugee camps of Calcutta almost overnight. “That traumatic event was never an easy thing to come to terms with,” he says, of the days that still haunt him. When he decided to become an artist, he found inspiration and solace in the terrain of his childhood. “I grew up around water. The river always made a distinct sound. There was marshy land and green fields as far as the eye could see. It was quite a magical experience, honestly,” says Haloi, who returned to his alma mater to teach in 1963. Besides bucolic landscapes depicting cows and sketches of village women toiling away, he recalls doing principally figurative paintings in the early years. One particularly memorable expedition took him to the banks of the Subarnarekha river.

“A woman had died by drowning in Subarnarekha. I tried painting that accident in various ways, hoping to give a tribute to the loss of a precious life,” he says. Exactly at what point did a figurative and landscape artist transition into a purveyor of infinite abstractions? Haloi recounts the specific moment in his artistic journey when an epiphany washed over him — a time came when he was grappling with questions like, ‘How can an artist express fear? How can you paint sentiments?’ Elaborating on this breakthrough, he says, “My paintings are born in pain. The pain of separation from my homeland. I was initially doing figures and landscapes but soon I started enjoying the non-figurative form because it gave me more freedom. You can only paint feelings with the help of something that is non-representational and not bound by strict formalism.”

There’s something dichotomous about Haloi’s idea of art germinating from pain and despair and then evolving into a delightfully fulsome palette. “Whether you are painting happiness or suffering, if you do so in a rhythmic manner I think it will be successful. After so many years of working, even today there are occasions when I feel I have not got it right,” he remarks, a touch hesitantly. Even though the artist’s vision and the alchemy of the canvas are complementary forces the twain seldom ever meet. But when they do, sparks fly. “Only once in a while does art give you vibration or a kind of shivering feeling. If you are lucky you will receive from the painting what you expected from it,” he says, nodding, “It happens.”

(Re-citing Land: Ganesh Haloi: Six Decades of Painting runs at Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation gallery, Mumbai, till January 11, 2023)