How Elif Shafak Became a Tree

The Turkish-British author’s new novel, set in Cyprus, tells of divisions and reunions through the prism of nature. The author speaks to Nandini Nair about inherited pain and memories, language and silences

Nandini Nair

Nandini Nair

Nandini Nair

Nandini Nair

|

17 Sep, 2021

|

17 Sep, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/ElifShafak1.jpg)

Elif Shafak (Photo:Ferhat Elik)

Elif Shafak’s Twitter handle reads, ‘Storyteller, Novelist, Writer, Reader, Learner, Human Rights Advocate, Feminist, Public Speaker, Introvert, Citizen of Humanity’. It is a long list, which just about captures Shafak’s wide repertoire, which includes being a bilingual writer and a professor in colleges in Turkey and the US. The Turkish-British author—who after staying for several years and writing several novels in Istanbul, lived in the US and wrote books in Boston, Michigan and Arizona—now considers London as one of her homes. Having written 19 books, 12 of which are novels, she is best known for The Bastard of Istanbul (2006), The Forty Rules of Love (2009), and 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2019.

In Turkey, she is both a celebrated and controversial public figure. In 2006, Shafak was tried and acquitted for “insulting Turkishness”. In 2019, Turkish prosecutors investigated fiction writers including her, and examined two of her novels for any description of child sexual abuse. She hasn’t been back to Istanbul in many years.

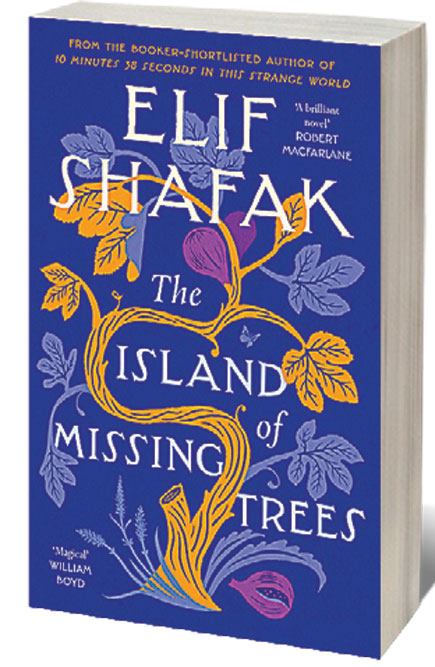

Shafak is now out with The Island of Missing Trees (Viking; ₹ 699; 344 pages) a parable about loss and belonging, where a fig tree plays a protagonist. The novel unspools the love story between Kostas a Greek Christian and Defne a Turkish Muslim. It is a book both about land and the earth. It takes the reader deep into the tree world, reminding us that “Trees are never lonely…loneliness is a human invention… Trees are much more alive than most people realise.” Through the voice of the fig tree, the novel often reads like a botanical exploration where every leaf speaks and every flower has a story. A novel that is both about arboreal time and human time, it chronicles the upheavals of the summer of 1974 in Cyprus, when Turkish troops entered the island. I learned many tree facts while reading this book. Did you know that the smell of a freshly mown lawn that we associate with summer dipped mornings is actually a distress signal shot out by the grass to warn other flora?

In the ‘Note to the Reader’, Shafak reminds us that “many of the stories of the missing mentioned throughout the novel are based on true accounts”. Defne in the early 2000s in Cyprus immerses herself in the Committee on Missing Persons (CMP) which worked meticulously to locate and identify the remains of those who had died during the war. Finding the bones of a loved one would bring closure to those who had mourned for the deceased. Defne recounts, “A few bones [of her husband], that was all we gave her [a widow], but she was as happy as if we had given her the world.” Burying and unburying, whether of the fig tree, or people, or memories or trauma is the central theme of the novel.

The Island of Missing Trees moves back and forth between Cyprus of the ’70s and London of 2010, where Kostas and Defne’s 16-year-old daughter Ada wonders at her father’s strange obsession with the fig tree. Dealing with the requisite teenage millennial traumas of online bullying, she must also grapple with her mother’s sudden death, her father’s grief and the unexpected entrance of her aunt Meryem who she has never met before. The novel wonderfully shows us how to be human is to be rooted in the natural world.

Speaking from London on a Zoom call, Shafak has an unusual warmth to her, she frequently apologises for her “long answers” and a distinct Turkish lilt inks her sentences. She sits framed by bookshelves, and a large blue ring on her pinky finger often flashes into view. She speaks in chunks of perfectly crafted quotable quotes. Edited excerpts:

The inscription in The Island of Missing Trees reads, ‘To immigrants and exiles everywhere, the uprooted, the re-rooted, the rootless..’ Are you the uprooted, re-rooted, the rootless, or all of the above?

Thank you. It’s a beautiful question. It’s a challenging one too. Because these are not easy issues to talk about, emotionally, but I do. I do think about what does it mean to be uprooted? Deracinated, almost rootless. What does it mean to belong? Or a non-belongings’ exile? These are all issues that are very, very close to my heart. I’m someone who believes in multiple belongings, but also I’m someone who’s not a stranger to exile and immigration and displacement.

Could you tell us how you decided to make the fig tree the protagonist?

I have been wanting to write about Cyprus for a very long time, but it’s not an easy story to tell because in Cyprus, first of all, there’s no doubt that it is a beautiful island with beautiful people on both sides, North and South, but it’s a place where the wounds are still open and there are clashing memories.

It’s a place that has experienced partition, division, ethnic violence. How do you tell the story of such a complex place without yourself falling into the trap of nationalism or tribalism? I couldn’t find an angle into the book until I found the fig tree. Looking at the story through the perspective of the fig tree gave me a completely different opening and a sense of freedom and I think it was also shaped by the pandemic too.

I’ve been reading about trees for a long time now, but the pandemic helped me to take the plunge and write about trees in a more urgent way and the tree gave me the angle or the opening that I needed and the sense of freedom that I needed to dare to tell the story.

I remembered when I used to teach at Ann Arbour, Michigan, it was quite cold and there were some immigrant families there, who would come from Italy, who would bury their fig trees when the winters were too harsh. And then they would unbury the same tree. It’s a botanical technique to help the trees survive harsh climates. I started doing more research and then you realise there are so many immigrant families that do this.

That gave me the whole idea of burying un-burying secrets, un-burying the grief, the bones of the missing.

This book is incredible in terms of its botanical detail. You’ve this wonderful line, ‘Arboreal-time is equivalent to story-time…’ Could you elaborate on the affinity you feel for the natural world as an author?

Trees are remarkable and it’s just fascinating that there’s so much we don’t know about them. Still. Even though, especially in the last decades there has been a great body of scientific work that has taught us so much about trees. And we need to understand that trees are far more Sentient than we recognise. They do communicate both under and over the Earth. And if we pay attention, actually they’re much wiser than us in my opinion. They have lived longer than us.

One day we will all disappear, but they will still be alive. So we need to stop thinking of ourselves as the owners of the universe as the centre of everything or as superior to everything else. We need to get rid of our own arrogance as human beings and reconnect with nature.

I also like to think about arboreal time. As humans we prefer to think that time is linear, that tomorrow will be better than yesterday. Tree time isn’t like that, it moves in circles, circles within circles and it’s aware of patterns and repetitions. Tree time is closer to story time. Stories don’t move in neat linear progress, either. In life, stories don’t evolve like that, they come to us in bits and pieces as circles within circles. So, I wanted to show that affinity between story time and tree time.

‘One day we will all disappear, but they will still be alive. Trees will still be around, so we need to stop thinking of ourselves as the owners of the universe as the centre of everything or as superior to everything else. We need to get rid of our own arrogance as human beings and reconnect with nature.’ says Elif Shafak

Looking back, is there a particular tree that is rooted in your memory?

Many in my grandmother’s house in Ankara. I was born in France to Turkish parents. But after a while my parents got separated. My father stayed in France and my mother brought me to Turkey. So, I was raised by a very traditional superstitious grandmother until I was ten years old and she was an oral storyteller and in her garden there were sour cherry trees. Which I’ve never never forgotten. It’s very vivid in my memories how they would stain your hands. But how wonderful they tasted. But if you ate too much, they would give you a tummy ache.

Could you tell us about some of the personifications of trees, how much is drawn from research and how much from your imagination?

Well, it’s a mixture, isn’t it? I love doing research. I love and respect knowledge. I stayed in academia for long years. My background is slightly unusual, maybe for novelists. Because I studied political science, political philosophy, gender and women studies. But basically, what I did was interdisciplinary work. So, I love learning from history, philosophy, sociology.

I like to read fiction and nonfiction, from the East and West. If we only read the same type of books, I don’t think we’re learning enough, so it’s those cross disciplinary journeys that excite me the most. In that regard, there’s always research and knowledge.

However, I love to write with my—what I call—intuition. So there comes the moment when you feel like, ‘Okay, you can fly.’ You can use your wings now and from that moment onwards, when I start writing, I really don’t know where I’m going. I really don’t know where the characters are going to take me and I follow my instinct, my intuition, and from that moment onwards it’s just pure imagination, but for me to be able to come to that point, I really need to read a lot and know what I’m talking about.

The novel is essentially about what we bury and un-bury, and how silences can be corrosive. But parents (like Defne) often believe they are protecting their children when they tell them little about the past. How much should we bury and how much should be unburied for a family, and for society to deal with trauma.

We always talk about family stories, but we rarely talk about family silences, I think there are also silences that are transferred from one generation to the next, and it is possible for younger people in such families to almost sense those silences.

I have observed so many families, immigrant families, families in exile, but also any family that comes from a complex background. It’s always amazing to see these intergenerational differences. The first generation, usually they’re the ones who have experienced the biggest traumas, but they don’t have a language to talk about them.

And then the second generation, especially if there has been a migration and displacement, the second generation does not want to talk about the past because they’re busy building a new life, finding their feet. They don’t want to look back. They want to look forward. But it’s the third or the fourth generations, the youngest in the families who are interestingly asking the biggest questions about identity, family trees, histories, the stories of their ancestors or the memories of their grandparents.

So that kind of curiosity and courage is very interesting in the younger generations, and sometimes you can come across a young person carrying old memories or the memories of their elderly. I’m very interested in both inherited pain, which I think exists and also intergenerational memories and silences.

You have an interesting reference about how according to elderly Cypriot women an enduring memory is a curse. Too much remembering can be debilitating as well…?

Indeed. Because remembering all the time can be quite debilitating and it can make us resentful. So there has to be a healthy combination of remembering and forgetting, but in order to come to that point, we need to remember first. So memory is a responsibility. Once we are able to talk about the past in a more nuanced way, then we can expect people to start forgetting. But just to cover everything, sweep everything under the carpet and pretend it hasn’t happened, that wouldn’t help because it creates more accumulated anguish.

In the novel one character leaves Cyprus and one does not. Can you talk about this process of moving out (or not) personally?

It’s an endless dilemma, isn’t it? Whether to go or to stay, whether to leave or not to leave, and it’s something that also resonates with me.

I don’t go back to Turkey anymore and I miss Istanbul dearly and I carry the city with me. Just because you’re not physically there doesn’t mean you are disconnected in your psyche. Sometimes it’s the opposite. You carry places. You carry your motherland, you carry cities, the cities that you love in your soul, in your minds. Wherever you go.

There’s a certain melancholy that comes with that too. Maybe you might call it the immigrant experience, or the experience of exiles. There’s always a fracture there. You have built a new life elsewhere, but it doesn’t mean that you don’t carry an absence, you don’t carry a void in your soul.

But it’s not easy to stay either, and especially people who have stayed after Civil Wars, ethnic violence, partition, people who stayed and tried to heal the wounds, they have dealt with so much, so I have a lot of respect for people who stayed, as well. I wanted to show the duality because in this relationship the man leaves and the woman stays and their experiences are completely different.

What do you mean by you carry Turkey with you?

Sometimes a smell triggers memories. The taste of street food, the smell of roasted chestnuts. Suddenly it takes you to the places where you come from. It’s not like you can leave the past completely behind. Actually, it does continue to shape us. I feel emotionally very attached to Turkish culture. People. The food. The music. Women. Sculpture. Oral storytelling. But I feel very demoralised and depressed when I look at politics and politicians in Turkey and this is a country that does not have freedom of speech.

Turkey has been going backwards, falling more and more into ultra-nationalism, Islamism, authoritarianism, populist authoritarianism. It’s a very difficult place for writers and anyone who deals with words to breathe because in order to write you need freedom, freedom of speech. Anything you say can offend the authorities.

There are big political taboos in Turkey, but it’s also difficult to write about sexuality. You might be put on trial, you might be investigated, imprisoned, exiled, so it’s a very, very difficult environment in that regard.

I love the people. But I don’t like the politics.

In Turkey you have been at the centre of many storms. Have those kept you away from the country?

I don’t feel comfortable going back to be honest because it has become a difficult place for writers, for academics, for journalists, even for cartoonists. I have a lot of respect for humour. Losing that ability to make fun of people in power… This might seem like small things, but they’re so, so crucial. Art and literature need freedom and I don’t find that freedom in Turkey.

That doesn’t mean that I’m disconnected from the country mentally, intellectually, culturally. The subjects that I deal with always offend the authorities. I’m not only interested in stories I’m most interested in silences and the things we find difficult to talk about. The minorities always play an important role in my work. I don’t want to pay too much attention to the centre. I want to pay attention to the periphery, to the people who are marginalised, left out and left behind, pushed to the edge of the society, and looked down upon and dehumanised.

It’s them that I want to give more voice to and the moment you do that, the moment you bring the untold stories into literature, then you get into trouble. If you start questioning the Armenian genocide, if you talk about issues like child brides, gender violence, femicides. I’m talking about these issues because they are happening in Turkey. So instead of doing something about the problems, trying to help women, open shelters for women, the fact that the authorities are investigating fiction writers who write about these issues is just mind-blowing.

I want to give you these examples to show that it can be a very difficult climate for an author.

‘The subjects that I deal with always offend the authorities. I’m not only interested in stories. I’m most interested in silences and the things we find difficult to talk about. The minorities always play an important role in my work. I don’t want to pay too much attention to the centre’

In an interview you mentioned you can express melancholy and longing in Turkish and humour in English. You just talked about the importance of humour as well. Can you elaborate on that?

I do write in English, but as you can hear in my accent I am not a native speaker. I did not grow up in a bilingual house, so English for me is an acquired language. And I will always be a late comer, or a newcomer, an immigrant in this language, which means there’s always this gap between the mind and the tongue. The mind always runs faster and the tongue tries to catch up, as immigrants we are very much aware of that gap and it can be frustrating as well. But at the same time, it can be inspiring. It can help you to pay more attention to new answers, to concepts that can’t travel or can’t be translated easily from one language to another. I guess what I’m trying to say is I love language. Language is plural.

I do feel connected to both languages, Turkish and English, but in a different way. My connection with the Turkish language is more emotional. My connection with the English language is more cerebral, it’s more intellectual, and I need both.

But I realise over the years that if my writing has melancholy, sorrow, longing, I find these things much easier to express in Turkish, but when it comes to humour and especially irony and satire, I find them much much easier in English.

But, of course, this is a cultural difference, not only a linguistic difference.

What is the language of your heart?

It depends of course. When I write in English, I stay inside that language all the time, so I don’t go back and forth. I’ve been in the UK for the past 13 years now. In a way it has become my adopted land.

I do a lot of thinking in English, but then every now and then, especially when you get more emotional, a Turkish sentence just pops up, which is quite interesting.

The figure of the aunt Meryem becomes a portal into the world of superstitions. Many of the superstitions are also familiar to India, for example nazar or how Tuesdays are considered inauspicious. You also write how while “religions clash…superstitions on either side of the border coexist in rare harmony”. Can we talk about that?

I was raised by a superstitious grandmother myself. I was really immersed in that culture as a young girl. I was surrounded by women like Meryem, and these are women who are well meaning, they want to do good, but they don’t exactly know how, they don’t have a language to talk about difficult painful issues. And they want to feed you and they hold this naive belief that if they can feed you, the world will be a better place. If we could only sit around the same table and share, you know, break bread together, there would be less hostility, less animosity in the world, and in a way, food is their language. Food is how they communicate.

I’m very interested in the whole culture. I’ve never belittled, never underestimated superstitions and folk tales and legends and myths. I always try to understand where they’re coming from and also to me it’s mesmerising to see how they travel across borders. When you look at the superstitions shared by Greek mothers and Turkish mothers or Greek grandmothers and Turkish grandmothers, they are so similar, likewise as you said in India, when you look at so many superstitions practised by Hindu grandmothers, Muslim grandmothers, Christian grandmothers, there can be amazing similarities. So I want to go back into that common overlapping oral culture.

And if I may give you an example in the Middle East, we always have this baklava war. You know, the Lebanese say, ‘It is our baklava,’ or the Syrians say, ‘No, it’s our baklava.’ We Turks think we make the best baklava in the world and the Greeks say, ‘No. It’s us who make the best.’

But of course, the beauty of food is that it’s nobody’s baklava. It’s everyone’s baklava. That’s the thing; food doesn’t recognise these tribalistic nationalistic codes. It just travels equally. Superstitions travel and stories travel. So, I want to put more emphasis on those things that go beyond ethnic and religious boundaries, and constantly keep travelling.

Another part which resonated especially is this fear of happiness, because some cultures think that sorrow is sort of always around the corner. Do you think that’s especially true of old societies that have seen many conflicts?

Absolutely. And I think in that regard there are amazing similarities between old cultures, old societies that have gone through so much. They’re almost afraid of happiness or showing their happiness afraid of nazar, afraid that things can take an about turn. Not really trusting life. That’s always been very, very interesting to observe.

Many people across Western capitals, they aren’t like that. Maybe after 2016, after Brexit happens, Trump happens, people have started to realise that democracy is much more fragile and life is a little bit more delicate.

But in general, there was this assumption that the Western world was solid and the eastern world was liquid, more turbulent. But now we realise actually we’re all living in liquid times, so more and more I’m noticing such things in the Western world as well, but it’s the trait of usually old societies that have seen so much.

This was very much a novel written during the lockdown. How did the lockdown help (or not) the writing process?

I published a little booklet before this novel. It’s called, How to Stay Sane in an Age of Division and the reason why I wanted to do that is because I realised I was dealing with lots of emotions like anxiety and uncertainty. I remember, some publishers saying, with good intentions, when the pandemic kicked in, ‘It wouldn’t be a very big difference for authors because authors are solitary creatures. They are used to working from home.’ I disagree. It does affect us. It does affect anyone, everyone when so much is happening outside. When people are dying in their thousands, how can we not be affected? So, all of us we’re dealing with so many negative emotions right now.

And, of course, India, Turkey both have experienced so much grief with the pandemic. I’m not going to claim that I was isolated, and I found it easier. You’re very much in conversation with the world around you as an author all the time.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-AfterPahalgam.jpg)

More Columns

he Logic of Grace: On the Election of Pope Leo XIV Open

Rubio asks India, Pak to de-escalate but asks Sharif to stop support to terrorism Rajeev Deshpande

Pakistan Launches Another Wave of Attacks on India Open