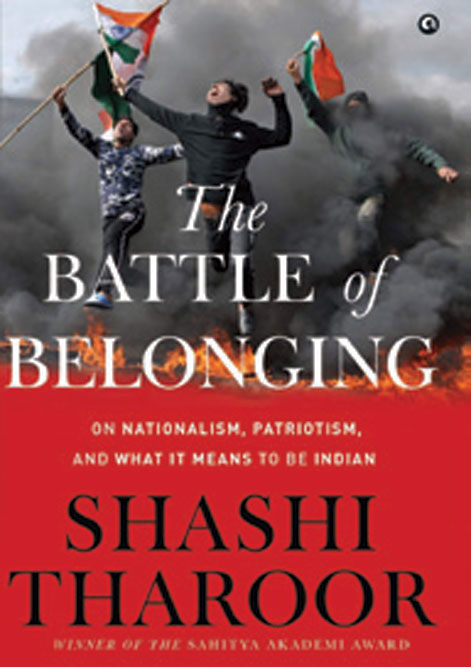

Who Is an Indian?

Being and belonging according to Shashi Tharoor

Mani Shankar Aiyar

Mani Shankar Aiyar

Mani Shankar Aiyar

|

08 Jan, 2021

Mani Shankar Aiyar

|

08 Jan, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Indian1.jpg)

(L-R) Vallabhbhai Patel, Mahatma Gandhi, Subhas Chandra Bose, BR Ambedkar (Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

ANYONE WHO HAS the stamina to read through the 400-plus pages of Shashi Tharoor’s The Battle Of Belonging: On Nationalism, Patriotism, and What It Means to Be Indian (Aleph Book Company; 462 pages; Rs 799) will come away staggered by the extraordinary scholarship on such meretricious display, besides wondering whether the author really has read all the sources he cites or because he has a research team that is expert at surfing the internet and picking up the juicy bits from the barebones of Wikipedia.

For, within the first 100 pages of explaining the word ‘nationalism’ in all its connotations, the reader is introduced to not only Greek philosopher Epictetus’ dialogue with Flavius Arrianus and Roman philosopher Cicero but also, through Kautilya and Ibn Khaldun, to the 17th century British philosophers, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, and then down to the French philosophers, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the Marquis d’ Argenson, to the 19th century French professor, Ernest Renan, and the German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer, besides the American Mark Twain, on to the 20th century (the most bloody in history) featuring Dušan Kecmanović, Jacques Derrida, Umberto Eco, Emilie Ashurst Venturi and George Orwell, till we reach the post-WWII world, which then features Kenichi Ohmae and Aihwa Ong, Hans Kohn and Francis Fukuyama, Ernest Gellner and Benedict Anderson, Arnold Toynbee, Alisdair MacIntyre and Liah Greenfeld, Amílcar Cabral, Frantz Fanon, Karl Popper, Yuval Noah Harari, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Pheng Chea and Theodor Adorno (translated from the German by EFN Jephcott), before arriving at the nineties and noughties’ stars, Jurgen Habermas and Mark Juergensmeyer, taking in along the way Josep Llobera, Anthony D Smith, EJ Hobsbawm, Umut Ozkırımlı, Yoram Hazony, Rich Lowry and Tyler Stiem. Phew!

The subcontinent too is represented, notably by the quotes from the Bangladeshi poetess, Nazneen Ahmed, and Pakistan’s A Azfar Moin. There is also no dearth of Indian names. Note, this is only a limited extract of the sources quoted, perhaps no more than 10 per cent. Alongwith the unread villagers of Oliver Goldsmith’s lines on the village schoolmaster in his poem ‘The Deserted Village’, one can only in wonder grow that ‘one small head could carry all it knew’. Yet clearly, Shashi Tharoor’s head does. For the endless sources, drawn from all over the globe and in numerous languages, are well integrated into the argument which basically differentiates between nine schools of ‘nationalism’ and the far more attractive idea of ‘patriotism’. (Although, to my startled surprise, Tharoor, having cited everyone else, sidelines Samuel Johnson’s notorious remark: ‘Patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel.’ Of course, although this is little remembered, Johnson was referring to the then standard judicial practice of allowing fit, young criminals found guilty, to escape the gallows by opting for ‘patriotism’, which in those days meant dangerous and often shortlived service in the merchant marine with which Britain was launching her Leviathan on the high seas to bring her unlimited riches and an Empire on which the sun never set.)

‘Nationalism’, says Tharoor, came into common use in English only after 1844. Indeed, for several decades thereafter, ‘nationalism’ was a term of opprobrium in lands that were proud of their multinational imperial possessions, such as ‘the British, the French, the Ottoman, the Austro-Hungarian’. It was the Americans who ‘inaugurated a new idea of nationhood born of a unified people with common political and economic interests, under a system combining democracy with capitalism’—yet it was founded and embedded in the evil precept of ‘nationhood’ applying only to white, English-speaking, preferably Protestant males. Slavery was allegedly abolished by Proclamation in 1863 but it was not till 101 years later that the Proclamation was codified into the Civil Rights Act of 1964; the struggle continues, as can be seen in the contemporary ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement.

In Europe, it was the revolutions in Italy, led by Giuseppe Mazzini, Count of Cavour and Giuseppe Garibaldi, and in Germany under Otto von Bismarck, that made ‘nationalism’ the much-lauded norm, at least in their respective countries, by bringing together in ‘one nation’ dozens of principalities and mini-kingdoms. Yet, it was precisely in these two countries that fascism under Benito Mussolini and nazidom under Hitler showed within half a century how a ‘noble’ concept like the ‘nation’ could be perverted into the vilest behaviour known to humankind.

The point of departure must be: do the nuances of the meaning and implications of ‘nationalism’ and ‘patriotism’ that have haunted Europe—a continent of around 40 nations inhabiting a tithe under the surface area of one India—hold any answers for the integrity and independence of our land? More relevant for existential India are the issues of ‘unity in diversity’ or ‘unity in uniformity’

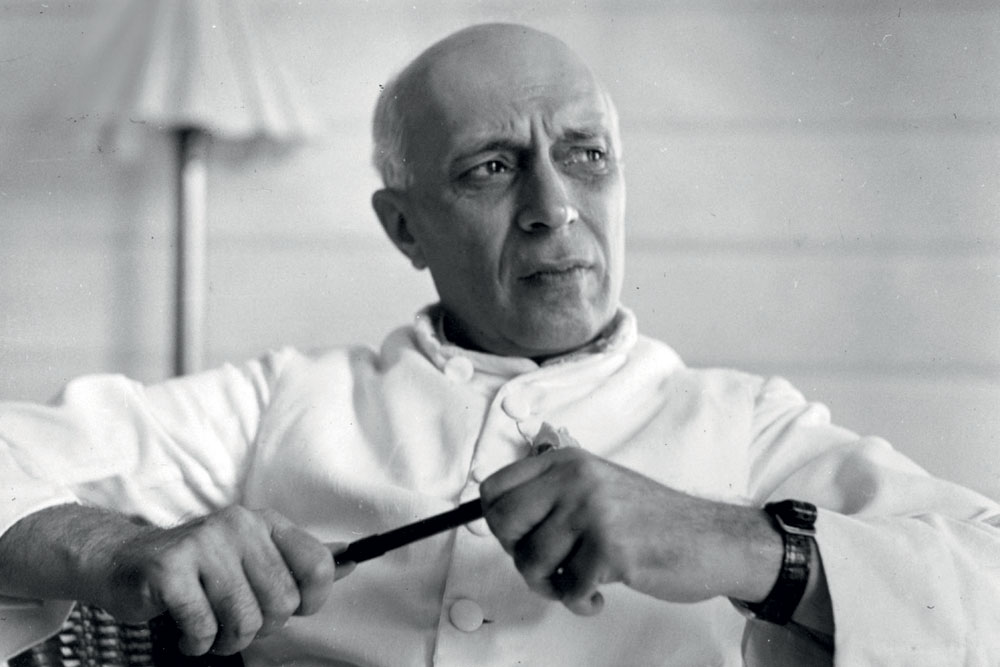

Distilling these philosophical ruminations and historical developments, Tharoor identifies (page 21) his nine categories of nationalism: ethnic, linguistic, cultural, religious, territorial, radical or revolutionary, anti-colonial nationalism, diaspora nationalism and civic nationalism. Many of these overlap or form hybrid nationalisms such as, in India, the ethnoreligious-cultural-diaspora nationalism of the saffron brotherhood, on the one hand, contrasting with the territorial nationalism evolving from anti-colonial nationalism into civic or constitutional nationalism of the mainstream freedom movement. This latter form of nationalism is associated with Mahatma Gandhi, Sardar Patel, Subhas Chandra Bose, BR Ambedkar and many, many others, and, above all, the Nehruvian ‘idea of India’, a term attributed to Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore, that Nehru definitively set out in his The Discovery of India (first published by the Signet Press, Calcutta in 1946).

In Tharoor’s native Malayalam, ‘rashtrabhakti’ apparently means devotion to the state or polity (nationalism) while ‘deshbhakti’ denotes love of one’s homeland (patriotism). ‘Patriotism,’ writes Tharoor, ‘accepts the great reality of diversity; nationalism seeks to obliterate diversity and create the world in its own abstract theology of supremacy.’ I am not sure I quite understand. Was Allama Iqbal being a ‘nationalist’ when he wrote ‘Sare jahan se accha/ Hindustan hamara’ (an expression of the ‘theology of supremacy’) and a ‘patriot’ when in the next verse he wrote inclusively of our rich diversity, ‘Hum bulbule hain uski/ Wo gulistan hamara’ (We are its nightingales, and this is our garden)? Perhaps the answer lies in Mark Twain whom Tharoor quotes: ‘The only rational patriotism is loyalty to the nation all the time, loyalty to the Government when it deserves it.’ Or George Orwell whom Tharoor also quotes: ‘By ‘patriotism’ I mean devotion to a particular place and a particular way of life. Patriotism is of its nature defensive, both militarily and culturally… Nationalism, on the other hand, is inseparable from the desire for power… (not for the individual but) for the nation in which he has chosen to sink his individuality.’ Orwell goes on, ‘While nationalism can unite people, it must be noted that it unites people against other people.’

All this has a particular historical context: that of Europe in the 25 years between the end of WWI and the end of WWII, the period during which Orwell went from being virtually a communist to penning Animal Farm and 1984. How relevant is all this to an India where ‘the Battle of Belonging’ is being fought today as never before? At one level, very relevant—for both Savarkar and Nehru were admirers of Mazzini and Garibaldi and drew the inspiration for their own avowed ‘nationalism’ from the Italian example. When it came to nationalism uniting ‘people against other people’, neither Savarkar nor Nehru wanted to unite Indians to dominate over other nations and peoples. That had been the bane of Europe through history and became particularly acute during the first half of the 20th century. What Savarkar wanted was for Hindu civilisation to dominate and end the pernicious outside influences that, in his view, had polluted our ancient land but, in Nehru’s view, had enriched it. So, the reader is inclined, after 100 pages of this ‘narcissism of minor differences’ through the linguistic parsing of the difference between ‘nationalism’ and ‘patriotism’ in a Europe divided into linguistic and religious homogeneities, to protest, ‘Thank you Mr Tharoor—but can we please get on with the ‘Battle for Belonging’ in India?’

And the point of departure must be: do the nuances of the meaning and implications of ‘nationalism’ and ‘patriotism’ that have haunted Europe—a continent of around 40 nations inhabiting a tithe under the surface area of one India—hold any answers for the integrity and independence of our land? More relevant for existential India are the issues of ‘unity in diversity’ or ‘unity in uniformity’. Are we proud only of being the inheritors of ancient India, and to thus build our national identity by ignoring or rejecting or ‘othering’ the 666 years between Mohammed Ghori seating himself on the empty throne of Delhi in 1192 CE till the dethroning of the last Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, in 1858? Or are we to take pride in the rich historical diversity in our land that through history has been open to thoughts and doctrines and ways of life that have made us the colourful, bubbling India we are?

Tharoor gets to that eventually at, literally, page 100 of his tome—and then does a pretty thorough job of it. ‘Citizenship is about the conferral of rights of participation in the national collective; identification relates to the emotive dimensions of belonging.’ One would hope that could be expressed in fewer and more simple words, but readers will forgive Tharoor his circumlocutions and rodomontade as the author proceeds to illustrate, illuminate and expound upon his basic propositions over the next several hundred pages.

The fundamental juxtaposition is between the ‘Idea of India’ (Section Two) and the ‘Hindutva Idea of India’ (Section Three). Tharoor argues—and I agree with him all the way—that the ‘modern idea of India… is a robustly secular and legal construct based upon the vision and the intellect of our founding fathers’ (who notably did not include any member of the saffron tribe). He emphasises, rightly in my view, ‘the role of liberalism in shaping and undergirding the civic nationalism of India’. I would also highlight his fundamental perception of the meaning of ‘secularism’ in actual political practice: ‘Even though India was partitioned… [India] embraced the Muslims who remained and sustained them through an official policy of secularism.’ He could have added ‘despite Pakistan evidencing little similar compassion for its Hindu minority’. It was this that resulted in the Mahatma’s assassination by Nathuram Godse of the saffron brotherhood. And it is this ‘official policy of secularism’ that was subsequently decried by the religious right as ‘pseudosecularism’ built on the ‘appeasement of the minorities’ to create a ‘votebank’ for the Congress. This is what lies at the heart of the contemporary ‘Battle of Belonging’ for our minorities. It is the litmus test of whether we are an India for all Indians equally, as prescribed in our Constitution (constitutional nationalism), or whether by ‘nationalism’ we mean, as the saffron brigade does, an India in which all are equal ‘but some more equal than others’. To put it bluntly, this is the principal motivating force behind the saffron brotherhood’s espousal of the ‘Majoritarian State’—that is the title of a publication with the subtitle ‘How Hindu Nationalism Is Changing India’ (HarperCollins, 2019), edited by Angana P Chatterji, Thomas Blom Hansen and Christophe Jaffrelot, comprising stinging analyses by a host of academic experts on every aspect of the Battle of Belonging. It is curiously missing from Tharoor’s otherwise long and detailed bibliography. (He has, however, cited one—just one—of Jaffrelot’s prolific contributions to the subject, Hindu Nationalism: A Reader (Princeton Press, 2007).

How relevant are European debates to an India where ‘The Battle of Belonging’ is being fought today as never before? At one level, very relevant—for both Savarkar and Nehru were admirers of Mazzini and Garibaldi and drew the inspiration for their own avowed ‘nationalism’ from the Italian example. When it came to nationalism uniting ‘people against other people’, neither Savarkar nor Nehru wanted to unite Indians to dominate over other nations and peoples

I think this book might have been improved if instead of citing myriad authorities from distant lands reflecting on issues from a distant past, the author had more intensively supplemented his sources by more contemporary commentary (including this reviewer’s Confessions of a Secular Fundamentalist, Penguin, 2004). For the Battle is here, not in ‘Old, unhappy far-off things/ And battles long ago’ (Wordsworth, ‘The Solitary Reaper’).

‘Pluralism,’ argues Tharoor, ‘is a reality that emerges from the very nature of the country; it is a choice made inevitable by India’s geography and reaffirmed by its history.’ He ends with ringing affirmation, ‘That is the India I lay claim to.’ Yet, that is precisely the ground—history—on which the ‘Hindutva Idea of India’ challenges the ‘Idea of India’ by asking whether pluralism/secularism need to be ‘reaffirmed by [India’s] history’ or repudiated on the same ground? Whereas Tharoor (and I) would agree that India’s is ‘a non-European nationalism’ (which is why I think the prodigious effort and expertise put into the first 100 pages of this work is of little relevance to the theme of this volume, which is our Battle of Belonging), our Indian nationalism revels in ‘embracing, indeed celebrating and guaranteeing its own diversity’ and ‘the Nehruvian legacy [is] a vigorous rejection of India’s assorted bigotries and particularisms’. The alternative Hindutva idea of India, on the other hand, is a vigorous affirmation of these ‘assorted bigotries and particularisms’. It is completely lacking in compassion or concern for the minorities. The Hindutvists would reel back in horror at Wajahat Habibullah’s assertion, based on historical fact, that ‘the bulk of India’s ruling class was Hindu since at least the seventeenth century’ (My Years with Rajiv, Westland, 2020, page 90). Thus, the contested terrain is our medieval history. The interpretation of that history is not the theme of the book; instead, we have the conclusion put forward with the author’s trademark elegance: ‘Indian nationalism is the nationalism of an idea—emerging from an ancient civilization, united by a shared history, sustained by pluralist democracy under the rule of law’ (page 130). Fair enough. Professional historians ranging from Romila Thapar and KN Panikkar to Mushirul Hasan and Irfan Habib have long laid to rest the invidious portrayal of that period as an uninterrupted tyranny of a religious minority over a religious majority—and, therefore, to be avenged.

Constitutional nationalism needs to never forget BR Ambedkar’s injunction, cited by Tharoor, that ‘Democracy in India is only a top dressing on an Indian soil which is essentially undemocratic.’ That is why ‘constitutional morality’ more even than the letter of constitutional nationalism is the imperative. It is not enough to kiss the entrance to Parliament House and declare Constitution Day on the anniversary of the day the Constitution was adopted; it lies, in the founder’s words, in ‘building up the feeling that we are all Indians… I do not want that our loyalty as Indians should be in the slightest way affected by any competitive loyalty, whether that loyalty arises out of our religion, out of our culture or out of our language….I want all people to be Indians first, Indians last and nothing but Indians’ (page 138). That is why the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, the National Register of Citizens and so much of recent state and Central legislation are repugnant to ‘constitutional morality’. That is also why on the question of ‘a penal code more in tune with civic nationalism’ I part ways from Shashi Tharoor. An India without community personal laws cannot claim to be a paragon of secularism or pluralism, an essential component of which must be reinforcing community identities and preserving/promoting minority interests as key components of a secular polity and ‘unity in diversity’. Was Tharoor himself not affirming his community identity when he opposed the implementation of the Supreme Court ruling on the entry of menstruating women to the Sabarimala shrine? And does his endorsement not contradict the sentiment and logic of his final words in the section ‘Idea of India’: ‘Each Indian is free to nurture multiple identities: regional, religious, caste, linguistic, ethnic’—especially as he himself feels ‘secure in each of these identities because of the sheltering carapace of one overall identity: that of being Indian’ (page 162)?

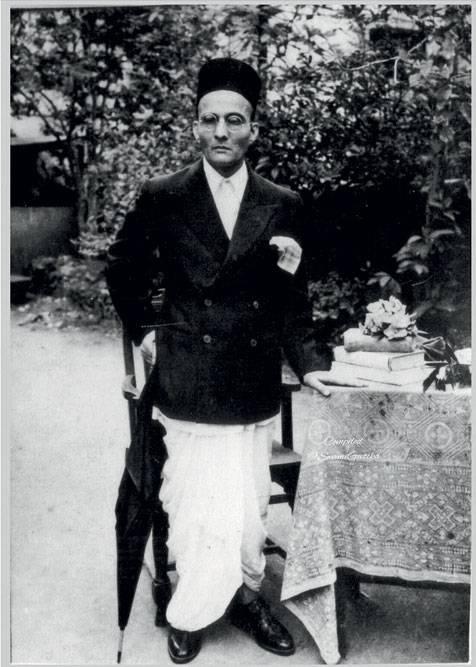

What then is the alternative ‘Hindutva Idea of India’? Tharoor takes us by the hand, as it were, on a quick, guided tour through Savarkar, Golwalkar and, finally, Deen Dayal Upadhyaya. Savarkar, the founder and patron saint of Hindutva, is etched somewhat sketchily in just three pages through such quotes as ‘Hindutva [should not be] confounded with its other cognate term Hinduism’. Savarkar’s idea of India is then cited for lauding what he calls the ‘Hindu race’ and defines this ‘race’ as ‘bound together’ by ‘a common fatherland’, by ‘common blood’ and, above all, by ‘the tie of common homage we pay to our great civilization—our Hindu culture’. Paradoxically, Savarkar affirmed his personal atheism, did not follow the rites and rituals of the Hindu religion, denounced the caste system and expressed a strong aversion to Hindu sants and sadhus, strongly disfavoured cow worship, flaunted his ‘staunch rationalism’ and sought ‘rapid social transformation’—on all of which points he was at one with Jawaharlal Nehru. Because Tharoor does not examine these points of commonality—plus their joint admiration for Garibaldi—his book also does not dwell on where they parted ways. This is a pity because the heart of Savarkar’s extolling an alternative idea of India lay in his bitter disagreement with the Gandhi-Nehru idea and was closest to that of Jinnah post-1940, namely that Hindus and Muslims constitute two incompatible nations.

Also, the role of non-violence both as an ethical ideal and an instrument of political action to drive the British back to their island-nation. Where Nehru avowed that if he were to turn to any religion, it would probably be to Buddhism, Savarkar regarded the Buddha as the fount of the downfall of Hindu civilisation because, he thought, it was such deviant thinking that had robbed the Hindu of his ‘manliness’ and rendered him vulnerable to the encroachment and eventual domination of first, Buddhism, then Islam and, finally, Christianity.

EQUALLY, WHERE SAVARKAR pours bile on Ashoka for his conversion to non-violence after the Battle of Kalinga, Nehru considered Ashoka as the greatest ruler of not just India but the whole world and cited HG Wells approvingly in this regard: ‘Amidst the tens of thousands of monarchs that crowd the columns of history… the name of Asoka shines, and shines almost alone, a star… More living men cherish his memory today than have ever heard of Constantine or Charlemagne.’

Savarkar’s dislike of the Buddha and Ashoka spilt over into an abiding hatred of Gandhi’s espousal of non-violence. The hatred was such as to make him complicit in the Mahatma’s assassination. All this is fully explained in the published and ongoing work of Vinayak Chaturvedi of the University of California, Irvine, who is arguably the leading contemporary academic authority on Savarkar, rectifying the balance after the treacly biography by the more frequently cited Dhananjay Keer. Curiously, neither of them is mentioned in the author’s otherwise amazingly comprehensive bibliography.

In complete contrast to Savarkar, Nehru neither favoured a cult of violence nor was willing to make violence a test of ‘manliness’. He was a pragmatic practitioner of the Gandhian doctrine of non-violence, humane, civilised. This is clear from his An Autobiography (first published by The Bodley Head, London in 1936; republished by the Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund in 1980, page 537):

‘Gandhiji impressed India with his doctrine of non-violence… Vast numbers of people have repeated it unthinkingly but without approval, some have wrestled with it and then accepted it, with or without reservation, some have openly jeered at it… The doctrine is of course almost as old as human thought, but perhaps Gandhiji was the first to apply it on a mass scale to political and social movements… Gandhiji tried to make this individual ideal into a social group ideal. He was out to change political conditions as well as social; and deliberately, with this end in view, he applied the non-violent method on this wider and wholly different plane.’

Nehru goes on to quote Gandhi: ‘Violent pressure is felt on thephysical being and it degrades him who uses it as it depresses the victim, but non-violence exerted through self-suffering… works in an entirely different way. It touches not the physical body, but it touches and strengthens the moral fibre of those against whom it is directed’ (emphasis added). In consequence, while Savarkar’s school celebrated and participated in the vicious communal violence that defined Partition, it was at that terrible time that Gandhiji’s belief in the effectiveness of non-violence and non-discrimination was best on display. He paid with his life for it—but it was in martyrdom that Gandhi definitively demonstrated the hollowness of Savarkar’s way.

Tharoor summarises rather more comprehensively Golwalkar’s contribution to the sharpening of the serrated edges of Hindutva through the ‘othering’ of Indians of non-Hindu faiths and invoking ‘race’ and ‘race purity’ as the distinctive characteristic of ‘Hinduness’. Carrying to its logical conclusion, Savarkar’s definition of ‘Hindutva’ as the establishment in independent India of ‘Hindudom’, as the equivalent of the establishment in Europe of Christendom, Golwalkar regarded ‘territorial nationalism’, as advocated by Gandhi, a ‘barbarism’ and ‘democracy as alien to Hindu culture’. In becoming passionate advocates of ‘cultural nationalism’ (as opposed to territorial nationalism), Golwalkar and his cohort’s principal inspiration was Hitler’s Germany:

‘To keep up the purity of its Race and culture, Germany shocked the world by her purging the country of the Semitic Races—the Jews. Race pride at its height has been manifested here. Germany has also shown how well-nigh impossible it is for Races and cultures, having differences going to the root, to be assimilated into one united whole, a good lesson for us in Hindustan to learn and profit from.’

(There is an important footnote here, number 202 on page 170, that notes the repudiation in RSS circlesof the ‘authenticity’ of Golwalkar’s We or the Nation Defined, first published in 1939. Tharoor comments: ‘The fact that he claimed authorship and promoted the book extensively, while not repudiating any of its tenets in his lifetime, vitiates the force of this disclaimer. Whether he wrote it or not, he was happy to claim its contents as his own.’)

I think the author could have usefully brought in BS Moonje who, after a visit to Italy, where he had been feted by Mussolini, came away so impressed that, in imitation of the Black shirts and rifles of the Fascisti, the RSS cadres were outfitted in uniforms and ‘lathis’ and organised into ‘shakhas’ where they were indoctrinated into Hindu ‘cultural nationalism’. This ‘cultural nationalism’ sought, says Tharoor, to establish ‘the hegemony of Hindus, Hindu values and the Hindu way of life in the political arrangements of India’, to the exclusion and demonisation of Golwalkar’s favourite enemies, Muslims: ‘Ever since that evil day, when the Muslims first landed in Hindustan, right upto the present moment, the Hindu Nation has been gallantly fighting on to shake off the despoilers. The Race Spirit has been awakening.’

Alongwith the unread villagers of Oliver Goldsmith’s lines on the village schoolmaster in his poem ‘the deserted village’, one can only in wonder grow that ‘one small head could carry all it knew’. Yet clearly, Shashi Tharoor’s head does. For the endless sources, drawn from all over the globe and in numerous languages, are well integrated into the argument which basically differentiates between nine schools of ‘nationalism’ and the far more attractive idea of ‘patriotism’

This spewing of hatred against India’s Muslim minority climaxed when, in the wake of the Partition riots, Golwalkar proclaimed that “no power on earth could keep Muslims in Hindustan. They should have to quit this country”. Golwalkar, concludes Tharoor, had ‘appalling ideas on how ‘foreigners’ should be dealt with… If Muslims, Christians (and communists) refused to convert or submit, they should be forced to quit the country at the sweet will of the national race’.

The author then moves to the most interesting chapter of his book, ‘Hindu Rashtra Updated’, which expounds the ‘updating’ of Hindu Rashtra by Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya, Vajpayee’s guru. His chief innovation was in rejecting Golwalkar’s ‘final solution’: ‘No sensible man will say that six crore Muslims should be eradicated or thrown out of India.’ In thus ruling out the Hitler-Golwalkar advocacy of physical liquidation, Upadhyaya opts for cultural genocide. ‘Every community,’ he argues, ‘must identify themselves with the age-long cultural stream that was Hindu culture in this country… unless all people become part of the same cultural stream, national unity or integration is impossible. If we want to preserve Indian nationalism, this is the only way.’ He goes on to say, ‘There are no separate cultures here for Muslims and Christians.’ Asserting that ‘Indian nationalism is Hindu nationalism’, Upadhyaya held that Muslims sought ‘to destroy the values of Indian culture, its ideals, its national heroes, traditions, places of devotion and worship’. He, therefore, recommended that we ‘nationalize Muslims… to make Muslims proper Indians’. This led later to Advani’s assertion that all Indians are ‘Hindus’; so, Muslims are ‘Muslim Hindus’ and Christians are ‘Christian Hindus’. So, I asked Advani what he was: “A Hindu or a Hindu Hindu?” Unsurprisingly, there was no answer!

The most interesting chapter of Tharoor’s book is ‘Hindu Rashtra updated’, which expounds the ‘updating’ of Hindu Rashtra by Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya, Vajpayee’s guru. His chief innovation was in rejecting Golwalkar’s ‘final solution’: ‘no sensible man will say that six crore Muslims should be eradicated or thrown out of India’

The Constitution repudiates all these false beliefs and prejudices. So, Upadhyaya rejected the Constitution as being ‘imitative of the West, divorced from authentically Indian ideas about the relationship between the individual and society’, rendering his ‘update’ resonant of Golwalkar’s denunciation of the Constitution ‘for incorporating ‘absolutely nothing’ from the Manusmriti’. And thus we find that whatever adjustments are made in the Hindutva ideology from time to time, quintessentially the ideology remains firmly anchored to the goal of a uniform if mythical Hindu Rashtra that irons out our native diversity and is pervaded by an anti-Muslim/anti-minorities ethos. To this has been added an intense dislike of ‘Anglophile Indians schooled in Western systems of thought’ (‘Macaulay ki aulad’, Macaulay’s bastards).

Although the second half of the book is given over to a trenchant and well-informed critique of Moditva (which we might label Hindutva 4.0), there is such widespread awareness of the excesses that the present Government has visited upon our benighted land that much of the remaining 200 pages reads like recycled columns on the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the proposed National Register of Citizens; on the Muslim women’s spontaneous protest gatherings against the Act and the Register at Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh that spread like wildfire to every nook and corner of the country; on the virtual abrogation of Article 370 and the subsequent atrocities visited upon the wretched, long-suffering Muslims of the Kashmir Valley; on the ‘etiolation of democratic institutions’; on the attacks on Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University; on Hindi chauvinism; on Ayodhya; on the continuing atrocities against minorities; and on a host of other painful issues of communal governance, at its worst in Yogi Adityanath’s Uttar Pradesh. And all of this leading to the final indictment: ‘The present ruling dispensation is remaking the country into a populist, communalist, chauvinist, authoritarian, slickly-marketed, and powerful kakistocracy supported by stoked-up vigilante mobs’ (page 381). But is it enough for us secular nationalists to throw the dictionary at our opponents? Are they going to bend before Tharoor’s thesaurus assault?

The question that remains is TS Eliot’s: ‘After such knowledge what forgiveness?’ How have we come to such a dreadful pass? Is it the obvious reluctance to firmly affirm, as Nehru did in the aftermath of Independence, a principled stand based on what I call ‘secular fundamentalism’? Or is it, indeed, secular fundamentalism that has led to this rightward, religion-bound orientation of the nation’s perception of itself? Can we revert—indeed, should we revert—to Nehruvian secularism? Or is ‘soft Hindutva’ responsible for lending so much respectability to hard Hindutva? Was there something dystopian about the wish, notwithstanding the secular acceptance of Partition as the price to be paid for Independence, to include the minorities as precious elements of our heritage to be valued in the present conception of nationhood? Or were Savarkar and Jinnah both right in seeing our two main religious communities as ‘two nations’? Rather than a detailed, if blood curdling, recounting of India’s drift under Modi to an illiberal, unconstitutional, communal and fearful ‘republic of hatred’, which is for all of us liberal nationalists a living nightmare, I would have preferred from Shashi Tharoor a searing conclusive analysis of how in the last six years, so many in this country (nearly 40 per cent) have surrendered to the pernicious assumptions and highly communal bias of the Hindutva ideology when, for almost the whole of the first half century of Independence, it was the people of India who had kept these very forces firmly at bay.

Shashi Tharoor is right in seeing salvation as a return from making India that is Bharat a ‘Hindu Pakistan’ towards liberal, democratic, constitutional values and norms and constitutional morality as the eventual solution to our current problems, but that is to remain in la-la land unless we first analyse why the nation has drifted so far from its Gandhi-Nehru moorings as to actually give the Savarkar bhakts over 300 seats in the Lok Sabha. Then to work out new approaches to oust Hindutva from the minds of our people. And, finally, on to the most humongous task of them all: selling these new approaches to our party. Three decades ago, we had a Congress prime minster who could boldly assert on the floor of Parliament, “India can survive only as a secular nation—and perhaps an India that is not secular does not deserve to survive.” Is there anyone who can pick up that gauntlet now?

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-AfterPahalgam.jpg)

More Columns

he Logic of Grace: On the Election of Pope Leo XIV Open

Rubio asks India, Pak to de-escalate but asks Sharif to stop support to terrorism Rajeev Deshpande

Pakistan Launches Another Wave of Attacks on India Open