Books | Best of Books 2024: Foreword

Orbiting in Ideas

In India, young nonfiction writers are telling us vital stories, of moving beyond presumptions, and widening the public discourse

Nandini Nair

Nandini Nair

Nandini Nair

13 Dec, 2024

Nandini Nair

13 Dec, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/OrbittinginIdeas1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

AT A TIME when ‘brain rot’ has been anointed the word of the year, it is clear that our attention spans are fracturing and our concentration has been shot to bits. The act of reading has been quickly hailed as the antidote to this degradation of our minds. Readers like to believe that they are better people than non-readers. But that is just a belief and not a fact. While brain rot might be particular to our times, the remedy lies not only in reading, but in any activity that demands our full and complete attention. This could be something as mundane as cooking a meal or as sublime as a walk in the woods. In the following pages you will encounter one way to counter “the supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state,” and that is by reading deeply and widely, and reading the ‘best’. The ‘best’ is always a subjective term, but given the variety of books on offer, from fiction to nonfiction, politics to poetry, you can be assured that the range will cover all choices and all preferences.

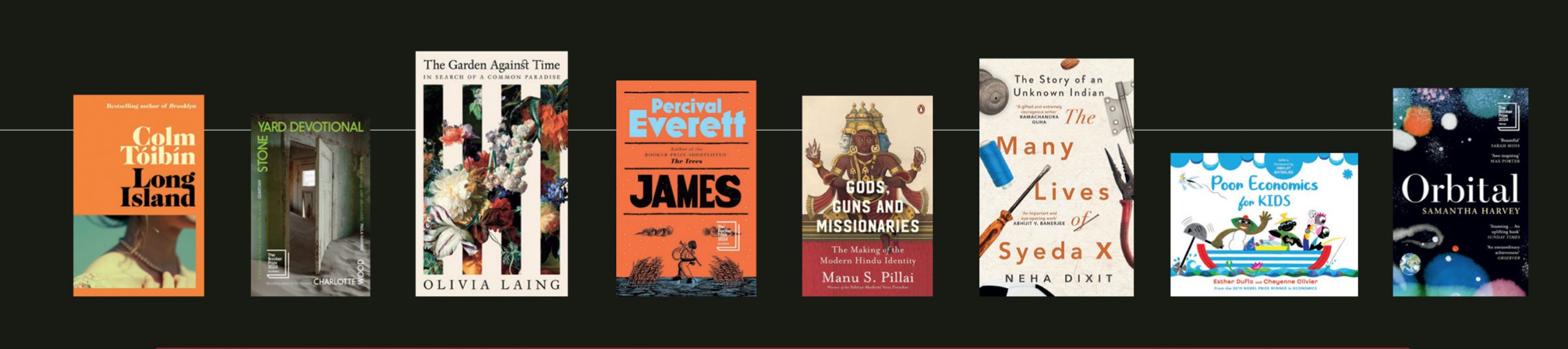

Only a handful of books appear more than once on the list of Best Books of 2024. And I too will begin with one of the repeats. Orbital by Samantha Harvey (Vintage) has won the Booker Prize and will thus be assured of a readership, and rightly so. By making us see Earth from afar she makes us see our planet anew. Devoid of narrative arc or plot line, it is a novel that holds its own with the sheer beauty of its prose and the acuity of its insights.

This year, I particularly enjoyed reading the books on the Booker shortlist, and there were two others which I found exceptional as well. James by Percival Everett (Mantle) was a top contender for the prize and could easily have won. Retold from the point of view of enslaved James, unlike Orbital it is an action-packed novel, which is likely to be made into a Netflix series or a movie sooner rather than later. It is once again a reminder of the brutality of slavery and the resilience of the human spirit. James as the literate slave who wishes to write his own story, who will go to unbelievable lengths to get a pencil, is truly an unforgettable character.

Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard Devotional (Sceptre) is another gem of a Booker book. I haven’t read too many novels from Australia and this one transports us there like a parent tucking a child into bed. It is comforting as you also feel you will soon be entering a new world, a dream world. I found something deeply moving about its protagonist who is seeking a retreat from urban life and finds comfort in a place more simple and more basic. In a shelter far from the urban world she re-evaluates her past, faces up to her grief and reconciles with her memories. It is a novel about forgiveness and families, reckonings and reconfigurings.

It is often said that Colm Tóibin is incapable of writing a bad sentence. And with Long Island (Picador) he once again proves this. While so many authors lose their brio with age, Tóibin only seems to get better, if that is possible. We are reunited with Eilis Lacey, the heroine of Brooklyn, and with Long Island we get a novel that is both cerebral and scintillating. Seldom do the workings of the mind and heart leave one at the edge of one’s seat, but Tóibin succeeds in doing just that.

As a reader, I tend to be partial towards fiction. But this year, a few nonfiction books held me in their grip. I’m an ardent follower of Olivia Laing’s work and her latest book The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise (Picador) once again establishes why she is one of the most important living cultural critics. She leads us into her garden, she takes us into gardens across the world, and she reminds us of the importance of tending to the earth and absorbing its beauty.

In India, young nonfiction writers are doing the important work of telling us vital stories, of moving beyond presumptions, and widening the public discourse. Two books that did that for me this year are Neha Dixit’s The Many Lives of Syeda X: The Story of an Unknown Indian (Juggernaut) and Manu S Pillai’s Gods, Guns and Missionaries: The Making of the Modern Hindu Identity (Allen Lane). Dixit’s book is an important piece of journalism and reportage that sheds light on lives that have been invisibilised in India. Pillai approaches history not through ideology but through people and characters and demonstrates how by complicating history it can come alive.

Finally, a book that I shall put under the Christmas tree for my young and curious nephews is Poor Economics for Kids by Esther Duflo, illustrated by Cheyenne Olivier (Juggernaut). This is a book that never underestimates its readers, while still educating them about vital concepts such as justice and equality, migration and movement.

Poor Economics for Kids like the many other books you will read about in the coming pages is a book to recommend and share. And what better gift can there be this year, than one that might stanch brain rot?

More Columns

The Heart Has No Shape the Hands Can’t Take Sharanya Manivannan

Beware the Digital Arrest Madhavankutty Pillai

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai