The Rite of Sacrilege

Behind the laddu controversy lies a long-running project of de-Hinduisation of Andhra Pradesh

Sandeep Balakrishna

Sandeep Balakrishna  Sandeep Balakrishna

Sandeep Balakrishna  | 27 Sep, 2024

| 27 Sep, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Ritesofsacrilege1.jpg)

Devotees at the annual festival of Sri Malayappa Swamy, the current processional deity, in Tirupati

TS VENKANNAYYA IS a lodestar in the annals of the Kannada literary renaissance that blossomed in the latter half of the 19th century and flourished unabated for an entire century. His father, Subbanna, worked in the government of Maharaja Krishnaraja Wodeyar III as a shekhdar (an officer in the revenue department at the taluk level, in charge of collecting land tax), a rather lucrative job in those days. A life-changing episode in his twenties holds a mirror to contemporary Hindu society.

It might sound unbelievable today but piety was the intrinsic trait of Hindu society that had not yet been infected by what Macaulay defined as “education”. Subbanna was no exception. He came from a traditional household that prized Rama bhakti above everything. Even on his official travels, he would begin his day’s work only after finishing his Rama puja and recitation of at least one sarga of the Ramayana.

On one such occasion, he arrived late before his boss, the amaldar (senior revenue collector), who had summoned him. The boss mocked Subbanna’s devotion, which he perceived as insubordination. This was Subbanna’s response: “Sir, the Puja and Parayanam were not done by the Shekhdaar. These practices do not fall under the purview of any law of any Government. They are inherent in my personality and inseparable from my life. No Government has the right to forbid them. Neither do you have any right to object.” The next moment, Subbanna wrote his resignation. A shocked and remorseful amaldar tried to disabuse him of taking this drastic step. Subbana’s reply: “Sir, I haven’t resigned owing to anger against you. As far as I am concerned, serving Sri Rama is greater than this Government job. He who gives food to the whole world won’t make me starve. My late father too, retired as a Shekhdaar. But his era was different. People still had unquestioning, unsullied devotion in matters of God and Puja. But now, times are rapidly changing. I’ve worked under you all these years and I know that you are a devout and Dharmic man. However, if tomorrow a Christian or Muslim or an Englishman sits in your place, would he have the same respect for my devotional practices? What would be my condition then? I would then need to either abandon my devotion to Sri Rama or quit this job. However, Government authority is an addiction, which can’t be given up easily. Who knows how my mind will change? It’s better I quit now.”

This ennobling episode occurs in the Kannada memoir Mooru Talemaaru (Three Generations) by TS Shama Rao. This episode is relevant in context of the so-called Tirumala laddu controversy.

The revelations are outrageous. Lard, beef tallow and fish oil were allegedly used to prepare the laddus, the ubiquitous Tirupati prasadam, which has a history of about three centuries. A poignant scene in Annamayya, the 1997 Telugu biopic of Tallapaka Annamacharya, the 15th-century saint, musician and poet, extols the sanctity of the Tirupati laddu by transforming the audience into participants in the scene. It shows Padmavati (Lakshmi) herself feeding the laddu to a lost, wounded and distraught Annamacharya, who is also celebrated as one of the foremost devotees of Sri Venkateshwara. That’s how the Hindu community across the world regards this prasadam.

This feeling of deep bhakti was assaulted for five years on the watch of former Chief Minister YS Jagan Mohan Reddy, himself a Christian. The global Hindu community watched in disbelief as Chief Minister N Chandrababu Naidu exposed the exact details of this assault on live TV. That this concoction was given as prasadam to millions of unsuspecting Hindu pilgrims on a daily basis, and the scandal was concealed for half-a-decade, makes it all the more gruesome.

But to those who have followed the events that have unfolded in (undivided) Andhra Pradesh since 2004, these revelations are unsurprising. And the defiled prasadam is just a minor outgrowth of an all-encompassing problem.

More than Punjab and Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh has emerged as the hottest frontier of the project to Christianise Bharatavarsha.

Although conversions had been occurring all along since the coming of the colonial Europeans, it received a fillip when YS Rajashekhara Reddy (YSR), Jagan Reddy’s father, became chief minister. Apart from using taxpayer money to dole out freebies to the Christian community, the project of planting crosses on the sacred Tirumala hills germinated in his tenure. He had to withdraw it in the face of a backlash. It was also during his tenure that thousands of hectares of temple lands in the Krishna-Godavari-Vizag coastal belt were auctioned off to those he allegedly favoured. Most of these lands had been donated by the Vijayanagara kings. For at least half-a-millennium, this region had been the nerve centre that had preserved the best traditions of Sanatana Dharma and was the repository of Hindu classical arts and learning. It is said that one would breathe abhijatya (classicism) just by stepping on its sanctified soil. Since YSR’s time, it has become a vast playground where churches of all denominations proliferate. To cite an example, Kuchipudi, the village eponymous with the classical dance form, is the victim of rampant conversions. Probe the cab driver out there, and he will tell you why Jesus is the only saviour and why even you should accept him if you want to save yourself. He is a first-generation convert. It only gets starker as you traverse wider and deeper in this belt.

About 400km north of Tirumala is another high-profile target for evangelism. This is the ancient Shivakshetra at Srisailam, whose glory has been described in graphic detail by the 15th-century Russian traveller, Afanasy Nikitin. Today, the entire stretch of the journey to its foothills reveals a spectrum of churches of varying sizes and denominations. Srisailam belongs to Rayalaseema, the stronghold of the YSR clan.

Every major tirthakshetra has not only been targeted but infiltrated by evangelists in unprecedented ways. For example, shopkeepers selling puja items in Mantralayam are converts but retain their Hindu names.

The history of Christian evangelism shows that it is vocal about its intent to convert but adapts and innovates with respect to tactics. Nowhere else in the world would you see an idol of Christ striking the pose of Sheshashayi Vishnu (Vishnu sleeping on his bed, the serpent Adishesha).

The controversy takes us back to the profound remark that Subbanna made to his boss: “[I]f tomorrow a Christian or Muslim or an Englishman sits in your place, would he have the same respect for my devotional practices?” Subbanna had uttered these farsighted words 150 years ago, when Hindu converts to Christianity had been a minuscule percentage in South India.

But nobody could foresee a situation where zealous Christians would be placed in powerful positions right on the board of the Tirumala Tirupati Devasthanams (TTD). By the government itself.

Between 2019 and 2024, almost no week passed without the Telugu media unearthing yet another alleged act of sacrilege committed at Tirumala by converts appointed as employees. Allegations of the sale and use of tobacco and the consumption of liquor and meat atop the sacred hill were rife. Even worse news emanated about the largescale pilferage of devotees’ cash offerings and the theft of Sri Venkateshwara Swamy’s jewellery. Arbitrary changes in the rules of darshan and various sevas compounded the injury. Former Tourism Minister RK Roja Selvamani faces serious allegations of accepting hefty bribes to facilitate darshan.

The other side of this coin is really unpleasant. The Archaka community at Tirumala, Srisailam and elsewhere had been terrorised into silence by the government-appointed executive officer. There are first-hand reports of imagined infractions by an Archaka—for example, for not showing “sufficient respect” to the said officer. ‘Respect’ could be defined as giving an ‘insulting’ look. What followed was unmitigated harassment, including unprintable insults targeted at the Brahmin community. The full truth of this saga, complete with its excruciating details is awaiting discovery. It remains stuck in the scared throats of these Archakas. If and when it becomes public, the defiled prasadam scandal will pale in comparison to the scale and depth of the near-destruction of Tirumala.

The end-goal of the Tirumala vandalism is evident. A calculated de-sanctification at all levels would, in the long term, discourage Hindu pilgrims from visiting it. This playbook is as old as the Christian usurpation of the so-called pagan Roman Empire. One only needs to read the heartrending Orations of Libanius (314-394 CE) who watched with his own eyes how the newly ascendant Christians dismantled all the ancient and sacred pagan edifices, institutions, altars and temples piece by piece. From within.

Transparency, morality and justice apart, the existential question of the Hindu community demands the public telling of the comprehensive tragedy of Tirumala under Jagan Mohan Reddy’s regime. If Naidu’s exposés are anything to go by, such an effort seems to be underway.

If this is the official facet of the assault on Tirumala, there is the grassroots or the societal facet. It is much more disturbing. Three instances will suffice. In October 2014, the Tirupati Urban Police arrested a man named Mondithoka Sudhir. Mondithoka, a self-styled “independent, fundamentalist Baptist”, was seen giving valuable intelligence about the sanctity of Tirumala to visiting foreign missionaries right on the hills. A video of this incident went viral on social media and led to his arrest. In plain language, he was enabling their recce of Tirumala.

A SIMILAR DEVELOPMENT IS the inroads that the evangelical juggernaut has made in the Telugu film industry, which maintains a powerful influence over Andhra (and Telangana) politics. Even a decade ago, it was rare to see overt evangelical messaging in Telugu films. That has noticeably changed since. And in the ‘real’ world, a section of converted Telugu Christians—including producers and financiers—are openly campaigning for the “recovery” of all Baptist lands in the state.

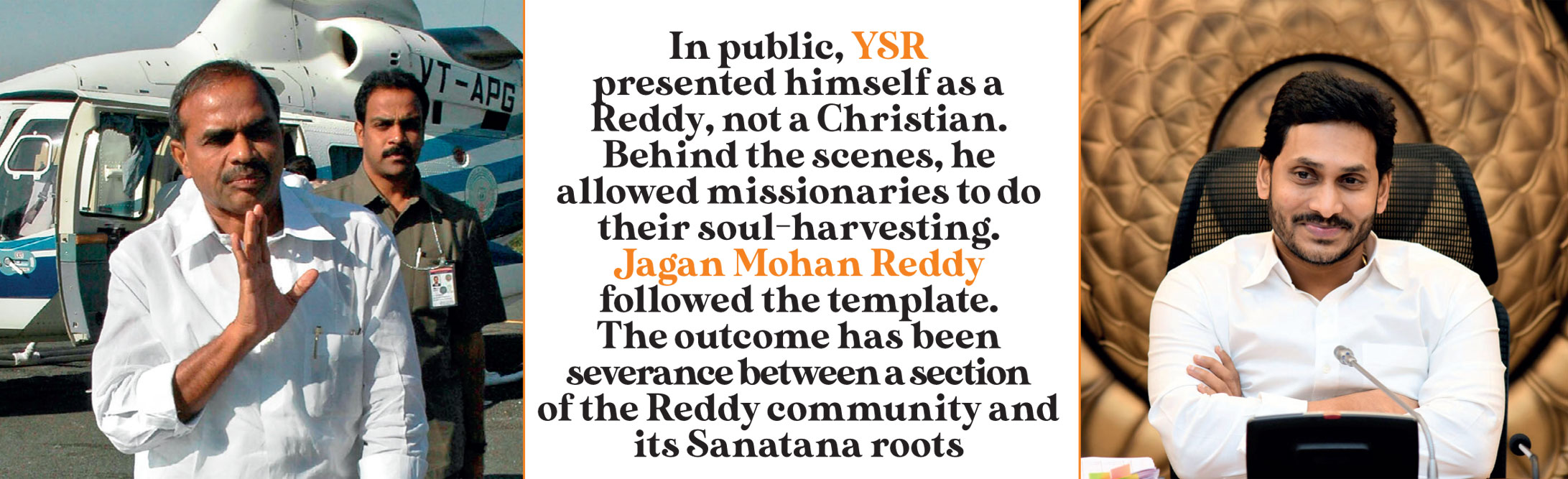

The last point leads us back to the YSR dynasty. His dramatic rise to quasi despotic power gave a renewed boost to Reddy politics, which had been the mainstay of Congress in Andhra since Independence. In public, YSR presented himself as a Reddy, not a Christian. Behind the scenes, he allowed missionaries to do their soul-harvesting. Jagan Mohan Reddy followed the same template with greater audacity. The net outcome has been the total severance between a section of the Reddy community and its Sanatana roots.

A scene in Annamayya, the Telugu biopic of Tallapaka Annamacharya, extols the sanctity of the Tirupati laddu. It shows Padmavati (Lakshmi) herself feeding the laddu to a lost, and distraught Annamacharya

An undefinable term has concomitantly arisen: Reddy Christian. This is a compound tragedy given that, in the 14th century, it was the virgin Reddy kingdom in coastal Andhra that had first ejected the alien Muslim invaders from Andhra from an expansive swathe of geography stretching from Visakhapatnam to Nellore. Prolaya Vema Reddy and his brother Malla Reddy explicitly and proudly mention in their inscriptions that the singular goal of their heroic war of Turushka liberation was to restore the primacy of the Vedic Dharma of which they were proud servants. The same region is today home to Reddy Christians and countless churches.

IT IS FUTILE AND foolish to solely blame evangelists for the Christianisation and de-Hinduisation of Andhra. Over the decades, the Hindu community has not only become slack but failed to erect unbreachable safeguards against encroachments on their dharma.

An inseparable part of agriculture is the incessant rooting out of weeds and pest control. For a combination of reasons, including infighting among the various Hindu sampradayas, Tirumala became lax in this regard. Which is why it became fair game so easily. All it needed was just one electoral victory. And what happened during Jagan Mohan Reddy’s subsequent misrule was a short-lived evangelical usurpation of Tirumala. There is no guarantee that it will not recur.

There is a twisted literary metaphor for what transpired in Tirumala even during YSR’s chief ministership. Around 2006, it became commonplace for pilgrims to see signboards proclaiming messages along these lines: ‘Christian missionaries are prohibited on the sacred Tirumala hills’, ‘Missionary activities will be strictly punished by law’, ‘Non-Hindus not allowed on Tirumala’, and so forth. These boards were displayed every few metres on the ascent up the ghats and throughout the Tirumala kshetra on the summit. This is an incontrovertible sign of an acceptance of defeat, a herald of weakness that seeks strength by being proactively defensive. One of the enduring illustrations of this enervated spirit is the reaction of a section of Hindu society when YSR died in a helicopter crash in 2009. It was said that this was Sri Venkateshwara Swamy’s punishment for YSR for trying to sully Tirumala by attempting to Christianise it.

While I sympathise with the sentiment that generated this response, it makes for a sorry spectacle in real life. All the glorious epochs of Hindu history unerringly show that while Hindus as a community were pious, tolerant and gentle by nature, they also knew the power of deterrence—and implemented it unhesitatingly. Likewise, the lowest points of Hindu history have been marked by a helpless resignation to the miraculous powers of some divinity for rescuing them. Unquestioning bhakti in, say, Venkateshwara Swamy elevates the atman and refines life on earth. But this should be accompanied by a conscious awareness of the cruel realities of this earthly life. If Tirupati Balaji did indeed punish YSR, what explains the ease with which his son was able to put Christian converts on the TTD board and among the staff?

Such responses from the Hindu side are the operative manifestations of what Sri Krishna described as kshudram hridaya daurbalyam (contemptible weakness of spirit) in the Bhagavad Gita. Without generalisation, it must be said that this Hindu affliction owes to a torrid mix of ignorance of their own dharma, their inferiority complex, greed, guilt, and an aversion to confront predators. No Venkateshwara Swamy can cure this self-inflicted weakness of spirit.

There is an instructive epilogue to the present, unflattering chronicle of Tirumala.

In 1543, Martim Afonso de Sousa, the fanatical Portuguese governor of Goa, embarked on a campaign to plunder and destroy Tirumala, erase all traces of heathenness, and plant a church there.

He couldn’t have chosen a worse time.

The all-powerful Vijayanagara Empire was at its zenith. Halfway through his misadventure, Afonso realised the enormity of his blunder when a messenger told him: “[E]ven if you go to Tirumala with overwhelming force—two thousand, three, or four plus ten thousand musketeers, be assured that the local people are so ferocious that they will dig out handfuls of earth and bury alive any number of Portuguese troops.” (Oriente Conquistado a Jesu Christo Pelos Padres Da Companhia de Jesus or The Conquest of the East for Jesus Christ by the Priests of the Society of Jesus).

Afonso chose discretion over valour and abandoned the endeavour.

Nearly 500 years later, it appears that Afonso’s objective has been partially achieved not by a foreign missionary or an army of crusaders but by second and third-generation Hindu converts. Without bloodshed. In a democracy. By getting voted into political office.

Clarity dawns when we place the beef and pork-laced laddu in this context.

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Cover-ModiFaith.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Defender1.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/ALoser.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/APassagefromIndia1.jpg)

More Columns

Madan Mohan’s Legacy Kaveree Bamzai

Cult Movies Meet Cool Tech Kaveree Bamzai

Memories of a Fall Nandini Nair