The Cult and the Kitsch

Kochadaiiyaan may have disappointed his fans. But the legend of Rajinikanth’s stardom will endure

Nandini Krishnan

Nandini Krishnan

Nandini Krishnan

|

28 May, 2014

Nandini Krishnan

|

28 May, 2014

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Cinema-Kochaida-main.jpg)

Kochadaiiyaan may have disappointed his fans. But the legend of Rajinikanth’s stardom will endure

Imagine a hundred porn stars reaching simultaneous orgasm. Imagine a crash of rhinoceroses tearing through a forest. Imagine a herd of elephants trumpeting at a temple festival. Add to this the drug-addled screams of teenagers when the name of their city is yelled out at a rock concert by the lead singer. You’ll have something close to the hysteria that accompanies the appearance of ‘SUPERSTAR RAJNI’, letter by letter, at the start of the titles of a Rajinikanth film.

The numerologically empowered Kochadaiiyaan is his first film in three years. The initial teaser trailer for the film, then titled Sultan, was screened in 2008. For nearly a year, his fans have faced a series of dhokaas, with the film’s release repeatedly getting postponed. Finally, after several name changes and a health scare for its star, the film is out, even as a new Rajini joke is doing the rounds—‘Rajinikanth hugged a chaiwalah, and he became Prime Minister of the country.’

Every time a Rajinikanth film comes around, people across India try to decipher the cult of Rajinikanth. This man was once a bus conductor, a carpenter, a coolie. How did he come to achieve such heights of fame and success? How did a dark, moustached man who built his career around flicking his hair back, flipping cigarettes into his mouth, twirling his sunglasses, and delivering ‘punchlines’ with a signature smirk become ‘Superstar Rajni’? How did a man who in his early days played a drunk, pornographer, rapist, murderer, and cheat, become a mass hero? There is no point trying to figure this out. There is simply no explanation.

I grew up at a time when Rajinikanth was making his transformation from villain to hero, from actor to star. He was instrumental in fostering the image of the ‘Madrasi’ as dark, moustached, and unattractive. He paved the way for heroes who were darker and more unattractive, and sported moustaches of varying girth, in the Tamil film industry. But his newfound cult in North India bewilders me. It may have been around the time his Enthiran/Robot released, co-starring Aishwarya Rai, that Hindi-speakers began to engage in the Superstar discourse. Already, there had been a paradigm shift in his Southern fan club.

In the late 1980s and 90s, there was a distinct Kamal-Rajini divide among fans, despite the two actors branding themselves as bosom buddies. Kamal’s camp comprised avid cinephiles and smitten women; Rajini’s fans were crazed masses who would rather see a man defy gravity and split one bullet with another than convincingly play a cancer patient or underworld don. But at some point, it became a style statement for the elite, even those who spoke pidgin Tamil, to say they were fans of ‘Thalaiva’—Rajini’s long-time epithet.

I go to Rajini films to point and laugh. I assumed most people did. Apparently, this isn’t the case.

“I mean, how can you actually like his movies? Or his punchlines? Or the ‘style’?” I asked someone who calls himself a ‘Thalaiva fan’. “This is a guy who goes ‘Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you’ when his sworn enemy compliments his ‘style’, right after insulting him. Come on.”

“The genius of the man is not in saying ‘Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you’,” my friend theorised, “But in selling the ‘Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you’. Throw anything at them, and his fans will go berserk.”

That is an interesting insight. Somehow, Rajinikanth, the man who could have become a ‘character actor’ in the 70s and early 80s—he played a man who killed his best friend in order to marry the latter’s girlfriend, only to end up becoming her stepson in Moondru Mudichu; he played a man who is undermined by poverty in Aarilirunthu Arubathu Varai; he was not afraid to play an abusive husband, or bully, or rapist. The complex characters he had successfully portrayed did not sell; the things that cost him the least effort moulded themselves into a composite that would be heralded as ‘Rajini style’. These could sell asinine storylines.

The watershed moment may have been the song Superstaaru yaarunu keytta, Chinna kuzhandhaiyum solum from the 1989 film Raja Chinna Roja. Literally translated, it means, ‘If you ask who the Superstar is, even a child will tell you.’ To my knowledge, this is the first time Rajinikanth was described as ‘Superstar’. After this, he veered towards comedy and potboilers, though he would occasionally use his acting abilities in films such as Mani Ratnam’s Thalapathi. The transformation of his screen persona was mirrored by a change in the public perception of Rajinikanth, the man. In the 80s, he was the actor with a temper, who beat up a reporter, broke a cameraman’s lens and screamed at fans at his wedding, who guzzled alcohol and chain-smoked. Since the late 90s, though, he has become the modest man who dyes his hair only for his daughters’ weddings, appears in public without a wig, and goes on carefully-chronicled pilgrimages to Himalayan caves. While journalists and fans alike wax poetic on Rajinikanth’s spirituality, few people make ironic remarks about the ostentatious showcasing of his simplicity.

It appears there are certain unwritten rules where Rajinikanth is concerned.

Often, Tamil film critics write carefully-worded reviews, because one ‘cannot bash a Thailava movie’. A few years ago, a hilarious spoof called Thamizh Padam got into trouble in the film industry because it ‘dared’ to mock a scene from Rajinikanth’s Sivaji.

One may occasionally hear of Rajinikanth’s business sense in choosing his films and roles. But his active participation in reinforcing his ‘Superstar’ epithet is rarely discussed. This man starred in a film with a song extolling his label. His own family organised a festival celebrating his 25th year in cinema. The producers of his film Chandramukhi (2005) ensured that it broke a 50-year-old record set by the Tamil film Haridas (1944) by keeping it running for 890 days in a theatre they own. And yet, Rajinikanth is considered a paragon of humility. It also seems the relative performances of his co-stars will impact their career graphs, and not necessarily in the way they should. Rajinikanth’s favourite co-stars over the years include Khushboo, Soundarya, Meena and Gouthami, pretty women who were happy to let Rajinikanth dominate scenes. On the other hand, Ramya Krishnan, who stole the limelight in Padayappa (1999), hasn’t worked with him—or in any significant role in the industry—since. In Kochadaiiyaan, the animation ensures that everyone except the Superstar looks like he or she belongs in a creature movie.

I wonder, though, whether these rules have changed; whether the cult of Rajinikanth is beginning to weaken.

When Chandramukhi was released, in 2005, I was a rookie journalist. On the day of the film’s release, I had to put together a radio package on its reception among fans. I wandered the city’s theatres in the lead-up to the first show. People who had camped out all night, in the hope of buying first-day-first-show tickets, clamoured towards me and grappled for the microphone. For Kochadaiiyaan, though, I had no problems finding multiple seats for a Saturday matinee when I checked online on Friday evening.

The quality of the graphics has been universally trashed. A friend described it as inferior to Age of Empires III. I wasn’t attacked when I commented that the animation allows Rajinikanth to dance with girls younger than his daughters without being impeded by arthritis. The makers of the film have pulled out all stops. Before the main feature begins, there is a short video on the making of Kochadaiiyaan, which ends with Rajinikanth’s BFF, Amitabh Bachchan, mispronouncing the film’s name and saying that Indian film history will now be classified as “Before Kochadaiiyaan” and “After Kochadaiiyaan”. The Rajini film formula stipulates that the star has a ‘punchline’, which is repeated at key junctures throughout the film. This is usually an inane pop philosophy pronouncement which will be duly revered by fans. However, the punchlines here are a dime a dozen, so many that the audience is not quite sure which ones to cheer for. In one song, he reels them off in the manner of a stand-up comedian in denial, trying desperately for laughs in a comedy club where everyone has been there, seen that. The problem of plenty extends to the songs—there is one every few minutes, and though a couple are truly stirring, even AR Rahman can do only so much—as well as to the star himself. There are three Rajinikanths, at last count, and we are not sure who the hero is—the father or his twin sons.

Kochadaiiyaan has been branded as ‘India’s first motion capture photo-realistic 3D animated film’—there are enough adjectives in there to ensure that the combination merits the qualifier ‘first’. But Rajinikanth’s participation in Kochadaiiyaan is largely seen as an indulgence of his daughter Soundarya’s directorial ambitions. Does this mean Rajinikanth is no longer invincible? Or does this simply mean that an animated Rajinikanth film will not sway the audience like a live-action Rajinikanth film?

It is early days, and one can’t predict how the film will perform at the box office. But assuming it is not as successful as the average Rajini film, one wonders whether Rajinikanth will be forgiven by filmgoers for giving in to his paternal instincts. In fact, his encouragement of his daughter could endear him to his fans, who delight in the human aspects of their celluloid hero. But, is this simply about his daughter? The film ends with the promise of a sequel, and it is an interesting time to speculate over Rajinikanth’s future in cinema. The 63-year-old actor is no spring chicken. Since he collapsed while shooting in 2011, he has been hospitalised often—for a gastro-intestinal infection, recurrent respiratory problems, kidney disorder, pneumonia, and pleural effusion. He has, perhaps, one last in-the-flesh film left in him, to let himself out with a bang. Perhaps this is an experiment, to see whether an animated Rajinikanth is acceptable to his fans, because this could be his future. If that is the case, the film’s middling reviews cannot simply be pinned on the movie’s failure to project Rajinikanth; it would be Rajinikanth’s failure to project the film, and that is a telling difference in this context.

Rajinikanth’s hold over people at large has often been compared to that of actor-turned-politician MG Ramachandran, popularly known as ‘MGR’. But there is a key difference. People related to MGR’s roles. He became Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu by consistently playing the poor man with a golden heart—the rickshaw-puller, driver, fisherman, desperado—who would tame and win over the fair, beautiful, rich, spoilt, spirited girl, usually played by Jayalalithaa. However, MGR was from a middle-class family, well-built, fair—almost pink, in fact, and made pinker by 1960s Technicolor. Rajinikanth, on the other hand, has lived the rags-to-riches story. Too impoverished to continue his education after school, he worked menial jobs. He went on to achieve incredible cinematic success, and married a young, fair, beautiful girl.

His legacy in Tamil cinema will be that heroes are relatable to the common man, in terms of appearance, profession, background and language, while villains are fair, good-looking, educated, rich, English-speaking men who will eventually get beaten up.

Perhaps the secret of Rajinikanth’s success is that, unlike most of his contemporaries—including Amitabh Bachchan—he has never allowed himself to be ridiculed for romancing girls half his age on screen. And he has done this by ensuring that he allows himself to age off-screen, creating a Dorian Gray-like effect. His films are escapist. To criticise them, or him, is to destroy the fantasy his fans want to believe is within reach. And so, one may wonder what may have become of him if he had remained an actor, and not turned into a star; one may vocalise the snide remarks that his films beg, but the cult of Rajinikanth will endure—because it symbolises hope, and hope will endure.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

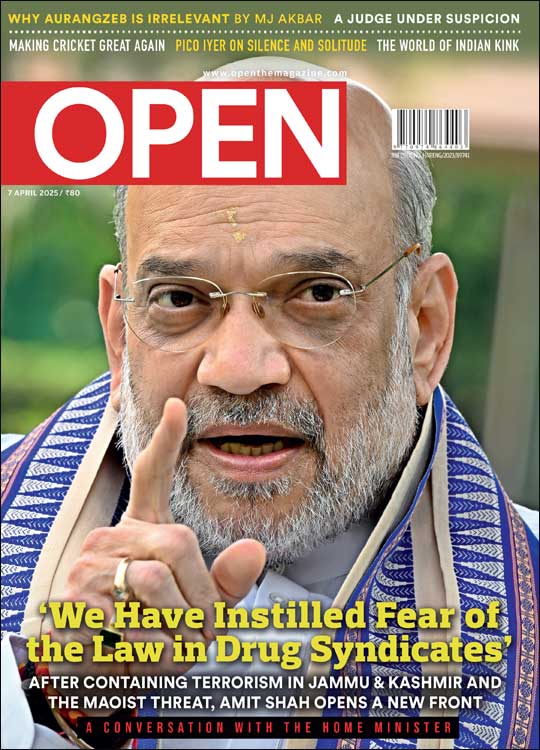

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

BJP allies redefine “secular” politics with Waqf vote Rajeev Deshpande

Elon Musk attracts sharp attack over ‘swastika’ from Indians on social media Ullekh NP

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh