Anurag Kashyap: ‘The system has always destroyed sportsmen’

Anurag Kashyap talks about his new film on the life of a boxer

Divya Unny

Divya Unny

Divya Unny

Divya Unny

|

17 Oct, 2017

|

17 Oct, 2017

/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/AnuragKashyap1.jpg)

It is day five at the 19th Mumbai Film Festival. Between catching some of the finest films from the world over, you also catch a glimpse of the man who has over the years become the festival’s signature face. He walks up and down the corridors of the festival venue, sometimes chatting with aspiring storytellers, sometimes posing for flashbulbs, and at other times just looking for the next good movie to catch. Anurag Kashyap started his journey right here, when his film Black Friday premiered at MAMI 12 years ago.

That film was banned and never saw the light of the big screen, but eventually went on to become a textbook example of fearless filmmaking in India. Today, Kashyap rushes me into a movie hall so we can have a quick chat before the screening of the much-talked-about Italian romance drama Call Me by Your Name (2017). “I really want to watch it,” he says almost with the enthusiasm of a child. The film, about a breezy yet heartbreaking summer romance between two boys in the quaint countryside of Italy, is not close to Kashyap’s cinema. But, of course, like any ardent film enthusiast, he is eager to follow the mind of a storyteller who doesn’t seem to belong to his world.

He chooses to sit bang in the centre of the cinema hall of velvet red seats. A massive, blank big screen ready to be inked by a new motion picture stares down at us. The setting is almost perfect. We chat as old and young film buffs swarm into the space, many even interrupting us just to greet him. “This is home ground for me,” says Kashyap whose newest film Mukkabaaz was the opening film at MAMI this year. The movie marks his first big return to his home turf of Uttar Pradesh since Gangs of Wasseypur (2012).

Mukkabaaz tells the story of a system that is hell-bent on breaking the spirit of a young sportsman who fights, primarily for love. His passion in the ring as a boxer arises from his burning desire to be united with his lover who belongs to a higher caste. Apart from addressing issues of caste and the burgeoning intolerance against beef-eaters in the country, the film highlights the haplessness of a sportsperson in India who has to fight numerous odds.

“When I started research on the life of a real boxer in this country, I was shocked,” he says, adding, “Apart from cricket, the system doesn’t really support any other sport in the country. If champions have emerged, it is only out of their individual passion. The system has always destroyed sportsmen, thanks to the political and the self-serving nature of the bureaucracy. If you attend an actual boxing tournament in the north, you’ll see that there isn’t anyone in the audience apart from people in power who decide which boxer should represent the state, and who will not. I saw an egotistic system which doesn’t really serve the sport, and I wanted to highlight that.”

Actor Vineet Kumar trained for a year to play the boxer’s role. Many stories of actual sportsmen came to the surface during this period. “Vineet was being trained by a coach Anudeep Singh and I asked him why he was coaching people for free, and how he makes his money. He told me how he runs a garage and that’s his income, and how he wanted to be a boxer but he could not play. It was heartbreaking to hear so many such stories of dreams being crushed every day,” the filmmaker says.

So for anyone expecting an inspiring tale of a sporting champion, Mukkabaaz is a jolt to reality. Kashyap’s protagonist is the flawed underdog, trying hard to keep his head above water. He is a reflection of the aam ambitious aadmi of India. But, as Kashyap says, it’s not enough to just have a dream or a degree in this country. “You have to manipulate your way through your dreams, and that reaches breaking point very often. I wanted to show that. Most sportsmen in India come out of the lower caste because it’s their way to find a job. I did not want to glorify the sport because that’s not the reality. I will fight for my rights with whatever bureaucratic system that has been put in place by the government. The film has come out of that.” he says.

THE SETTING IS credible, but the narrative often packs in too many issues at once. Mukkabaaz isn’t really a winner compared to some of Kashyap’s best previous work, but he is still confident of making a point. “My films have always been about society and people. I am not commenting on the empowered, but I am commenting on the basic people. I am one of them, or at least I was when I was growing up. I saw prejudice, and I stayed quiet. The first time you stand up and speak up for yourself you are suddenly told to toe the line, and today through my cinema, I want to fight that,” he adds.

I came from nothing, and so I had no one to please. My films were banned, but those bans empowered me a bit more

Kashyap’s cinema more often than not has been a mouthpiece for the regular guy on the street. The man is hardworking, often inconspicuous, and is trying his best to it make through the day. Sometimes the system breaks him, like in Mukkabaaz, and at other times he breaks the system, like in Satya (1998). It was Kashyap’s first film as a writer and today it seems like he has returned to being that young man who first came to Bombay. “It was at a film festival like this when I decided to pack my bags and come to Mumbai. I was studying to be a scientist then, and happened to watch some films at a festival in Delhi. Next thing you know, I was standing outside VT Station with a bag and nowhere to go,” he says.

It’s been 25 years since that day. “Has it been that long?” he jokes. Today Kashyap is the face of independent cinema in India. Emerging out of the shadows of his mentor and guide Ram Gopal Varma, here was a man who was restless to tell stories. His screenplays often shook his audiences out of slumber. He was one of the most complex storytellers of contemporary Indian cinema with movies such as the gritty Paanch (2003), the groundbreaking Black Friday (2004) and the discomforting Dev. D (2009). Despite growing up on larger- than-life Amitabh Bachchan classics, he chose to stick to reality with his films. He had the pulse of his middle-class audience. He did not care about making us viewers uncomfortable. Indie was the new mainstream, thanks to him.

“That’s who I am most comfortable being. I came with nothing, and so I had no one to please. Nobody expected anything out of me, and I was much freer then than I am now. I spoke about things that discomforted me and I didn’t care if I was at loggerheads with anyone. If someone agreed with me, they’d walk the same path. My films were banned, but those bans empowered me a bit more,” he says.

To Kashyap’s credit, he didn’t just carve a niche for himself, he also mentored other kindred directors. From Neeraj Ghaywan to Vasan Bala to Bejoy Nambiar to Ritesh Batra, some of today’s most promising filmmakers came out of the Kashyap School of Cinema. Ghaywan—whose film Masaan (2015), was produced by Kashyap, and won accolades worldwide—says, “When I started off with Gangs of Wasseypur I would lug lights from one corner of the set to another. Anurag gave me a window, but would never tell me what to do. I had to find my own ground, and tell the stories I believed in. His journey was what inspired so many of us.”

However, over the years it seemed like Kashyap has been sucked into the very system that he revolted against. When his most expensive venture Bombay Velvet failed in 2015, he felt lost, by his own admission. His vision was appreciated, but his craft was questioned. It seemed like in an attempt to pay tribute to his favourite filmmakers, he had done something self-indulgent. “I caught myself in that whole web of big budget, big studio expectations and that sort of thing. The minute it failed, I immediately saw how that wasn’t me. I am not made for that. I can’t function that way. I can admire other people who do it and navigate their way through it. But I can’t do it. The minute money becomes bigger than your story, you compromise and that takes away all the honesty you put into your film. It was a huge lesson for me,” he says. Now he’s not looking for a comeback, but just looking to tell the stories he wants to. “Gangs of Wasseypur cost nothing, but it’s a big film. Mukkabaaz looks like a big film, a full scale one, but it was made with small money. I would rather make big films my way with small costs. I don’t want to do resort filmmaking anymore,” he says.

KASHYAP HAS OVER 19 films to his credit as a director, and over 40 as a producer. He takes his films to festivals across the world (Mukkabaaz premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival) and he has multiple international co-productions in the pipeline. “I have much more freedom to be myself when I step out of the country because I don’t have to prove anything to anyone over there. People think I represent a certain kind of cinema, but among filmmakers abroad, it is not that. All of them just watch my work and move on, and [it’s the] same with me. I feel more natural, more rooted, more grounded. We interact like normal people, we try to understand the context of each others’ films and that’s about it,” he says. Kashyap is also among the first Indian directors to create an original Indian show, Sacred Games, in collaboration with Netflix. The show, helmed by Vikramaditya Motwane and Kashyap, is a digital adaptation of Vikram Chandra’s novel by the same name and is about Mumbai’s murky underworld scene against a tension-ridden political and economic backdrop.

With all of this, is he as independent as he was? “I am still very independent and I will fight for it till the end. Even today, people want me to repeat what has worked in the past. But I don’t want to do that. I want to push my boundaries, and very few understand that. So in that sense, the fight continues.” he says.

A group of his assistant directors walk by and greet him just before the screening begins. They research, write, shoot and edit Kashyap’s vision. He considers them almost like his children, but he is not interested in handholding them. “I abandon all of them after the film is made, because I want them to become their own person. This industry is a very ruthless place and if you’re thinking I’m going to be there, I’m not going to be there always. I encourage them to find their own company, do their own thing, take their own calls and I’ll just stand by them. ‘Make your own mistakes, hire your own crew, don’t run behind established names.’ I push them to do that. Give them three to four years and they are ready to be directors,” he says.

He now wants to tell the story of our increasingly volatile environment. “I want to communicate what I feel through my cinema even more now. There are a lot of things that bother me. I want to address them through cinema. It’s not to attack an individual, but attack a way of thinking,” he says. We wrap up the conversation just in time to watch a beautiful tale of gay love. “Nature has cunning ways of finding our weakest spots,” says the father to his son in the film. Lights on, and Kashyap quietly disappears into the crowd. Perhaps to find yet another way to tell us about our weakest spots, in the way he wants to.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

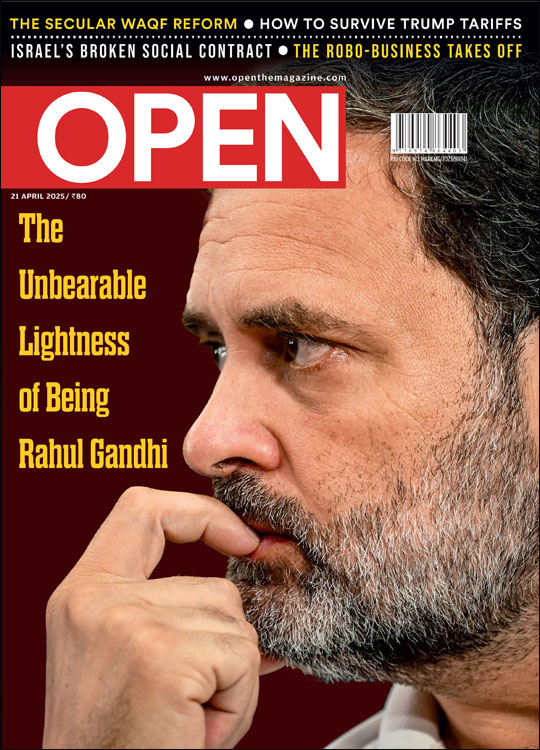

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Rahul Gandhi

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Cover-Congress.jpg)

More Columns

Maoist eco-system pitch for talks a false flag Siddharth Singh

AI powered deep fakes pose major cyber threat Rajeev Deshpande

Mario Vargas Llosa, the colossus of the Latin American novel Ullekh NP