Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay: The Last Teacher

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay taught me to look beyond the Great Man Theory of History

Gloria Steinem

Gloria Steinem

Gloria Steinem

Gloria Steinem

|

05 Apr, 2017

|

05 Apr, 2017

/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Lastteacher1.jpg)

THERE ARE SOME people who guide our lives, even though they enter them very briefly. For me, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay has played that role for a long time. Thanks to this important book by Ellen Carol DuBois and Vinay Lal, I’ve learned more of her writing, activism and life lessons. For readers who haven’t yet met her, her life will be a revelation. If Gandhi inspired and led a political revolution, she inspired and led a cultural revolution.

Her influence in my life began in the late 1970s. I had returned to India, where I had lived for two years as a student and wanderer almost two decades before. Devaki Jain, my friend and colleague from that first visit, had arranged a trip to see some of the women’s groups that had grown into a nationwide movement in the meantime.

Devaki and I soon found ourselves finishing each other’s sentences. Though we had been living thousands of miles apart, in New Delhi and New York respectively, a global feminist consciousness was spreading like wildfire, and it had illuminated both of our lives and all of our work. Women were challenging forms of male dominance in every country, from who controls the government to who controls women’s bodies and thus reproduction, from protesting violence against females in the street to protesting the absence of girls from schools. That is why Devaki and I had the idea of collecting Gandhian organizing tactics into a pamphlet for women’s movements everywhere. After all, his philosophy of satyagraha or non-violent resistance, and his tactics of massive demonstrations and consumer boycotts, would be well suited to women’s movements everywhere.

As part of our research, Devaki arranged for us to visit Kamaladevi, someone she knew and I did not. I understood from reading that this rare woman leader had worked with Gandhi over the years, led the Congress’ women’s organization, and pressed him to include women in the independence movement. She cautioned him against agreeing to the partition of India and Pakistan as a price of independence, and also insisted on the importance of handicrafts as a traditional means of livelihood. Despite the modern obsession with factories, mines and airlines in a newly independent India, she pointed out that for millions of villagers, whether in their homes or as refugees from what then had been partitioned into East and West Pakistan, handicrafts were a source of income and pride. Not only did such skills provide a livelihood locally, but they could become a unique global export. After all, other countries had factories, mines and airlines. India had millions—especially, but not only, female millions—who were experts in handicrafts that went far beyond Gandhi’s spinning wheel.

For all these reasons, I was eager to meet Kamaladevi, but I had no idea of what was in store.

We sat on her verandah, sipping tea and explaining our great idea of teaching Gandhian tactics to women’s movements. She listened to us patiently, waiting until we had finished what we thought was our innovative idea. Only then did she smile, wait a beat, and say, “Well, my dears, of course, we taught him everything he knew.”

This made us laugh—as one does in an “Aha!” moment of learning. Only then, as she continued speaking, did I begin to realize the enormity of what we hadn’t known or been taught. There had been a massive women’s movement for years before Gandhi and the nationalist struggle; one that protested sati, which meant the immolation of widows on a husband’s funeral pyre, supported the rights of widows to re-marry and girls to be educated—and many other hopes that had been stirred by a 19th and early 20th century global wave of activism, from the suffrage movement in democracies to women in the Middle East who threw their veils into the Mediterranean. When Gandhi was a young man studying in England to become a barrister, he also had witnessed the suffrage movement there—including the radicalism of Emmeline Pankhurst, one of whose daughters would later oppose the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, and represent that country and its culture in England. After he returned to India from South Africa, where he himself had been inspired by discrimination against him and other Indians, to organize against their second-class status, he urged activists agitating for self-rule and an end to British colonialism to emulate the courage and tactics of the Pankhursts. He also was alarmed to discover that the independence movement was centered in cities among the educated, and had almost no roots in the village life of ordinary people. It was then that he began to live like a villager himself, to take up the method of non-violence that he thought of as natural to women as nurturers, and to make the spinning wheel, a homely and mostly female tool, into a symbol of economic independence from British- made cloth. As his measure of success or failure, he used the change—or lack of change—in the life of the poorest and least powerful: the village woman.

This rare woman leader had worked with Gandhi, led the Congress’ women’s organization. She also cautioned Gandhi against the partition of India and Pakistan

As Kamaladevi kindly explained all of this to us, she noted that Devaki and I had been subjected by our schoolbooks to the Great Man Theory of History. We didn’t know the tactics we were drawn to were our own.

I realized what Vita Sackville-West, the English novelist, journalist and poet, had meant when she wrote:

I worshipped dead men for their strength

Forgetting I was strong.

Because of Kamaladevi, I also began to understand the politics of history. I would never again accept my history books so uncritically. Instead, I began to wonder why we don’t begin studying human history when humans began. We often dismiss ninety-five percent of the 100,000 or so years that humans have been around, call that “pre-history,” and only begin our study after patriarchy, hierarchy, monotheism, colonialism, racism, caste, class and other relatively new institutions began; thus they seem to us inevitable, a part of human nature.

In this way, I began to discover that on my own subcontinent, once known as Turtle Island, there had been consensus systems of governance as well as agriculture, medicine and egalitarian cultures that were more advanced than the hierarchical and monarchical systems of Europe. Even after colonial wars and disease had accomplished a genocide that is still the biggest in world history, the Iroquois Confederacy, a complex system of consensus governance that combined six nations spread over much of North America, inspired the US Constitution. These matrilineal cultures long pre-dated Columbus, yet were declared primitive by Christianity and colonialism. Still, they remained present enough to provide European women neighbours with a vision of female equality, and to be an inspiration for the suffrage movement.

All this I only began to learn after I had returned home from my second visit to India. I used to wish I could see Kamaladevi again, and share what I was learning. However, I had received new ideas from travelling to other countries, just as she did.

Because of Kamaladevi, I also began to understand the politics of history. I would never again accept my history books so uncritically

For instance, she opposed partition into a mostly Muslim Pakistan and a mostly Hindu India because she saw the lethal struggles that were resulting from a divided Ireland and a divided Israel and Palestine. As she wrote, “The concept of partition as a solution to multi-cultural and multi-religious problems has haunted us since that ominous partition of 1947. The British have been using this weapon wherever one of its colonies strove to come free of Britain’s colonial coils. Though we in India asserted that we did not believe in the two nation theory, by acquiescing in the partition at the behest of those who forced it on us, we seemed to have accepted it.”

How she might have mourned that partition now that Pakistan and India have still not reconciled, much less united. Kashmir remains a dangerous bone of contention. As I write this, Gandhi’s India has succumbed to Narendra Modi, a Hindu nationalist, as Prime Minister. He praises Gandhi but prosecutes Gandhians, censors the media, legalizes child labour, banishes civil society groups, and presides over a country in which a Muslim sometimes has difficulty finding a place to live, and is lynched because he consumes beef. Hopefully, this book’s permanent testimony to Kamaladevi’s life and work will survive into a more democratic future, but right now, the tolerance and glorious diversity of India that Gandhi championed, and Kamaladevi cherished, seems more vulnerable than ever.

Over the years, I’ve also thought of Kamaladevi whenever I find myself just as nervous about public speaking as I ever was. We choose our professions by what we do and don’t want to do. I chose to be a writer, partly because I did not want to talk. In the early days of the women’s movement, I found myself speaking —at first with a partner who was braver than I—because I couldn’t find editors willing to publish articles about this new contagion called feminism. Though I’m grateful for the shared understanding, empathy and hatching of ideas that happens in a room of people together—far more so than on the printed page or computer screen—I realize that I will never get over wishing that I didn’t have to talk. It’s then that I have the comfort of Kamaladevi, who cared about the future more than the present, and so who also went against her own instincts. “Some of us can be full of contradictions,” she confessed. “I seem bold, aggressive, out-going, having been a fighter all my life. But in reality, I am shy and retiring, rather averse to crowds and addressing large gatherings.”

She died at eighty-five. I am only four years younger. I have the comfort of reading her explanation that, “one suddenly becomes aware of an emerging end to what had seemed a continuing burgeoning. Each day, each year, one grows acutely aware, is taking that much of time out of the short span left. How long or short, it is not given to any of us to guess or know—something within only keeps warning you that it is getting shorter, quickly, fatally.” Though I plan to reach a hundred, I know exactly what she means.

Most of all, I’m grateful that because of this book, I not only know Kamaladevi better myself, but will have more company in my admiration of her. As a pragmatist and an idealist who refused to be contained by categories or expectations, her activism and beliefs caused her to spend time in six different prisons, yet she also travelled the world, including the United States, and defied barriers of gender, caste, race, nation, and religion.

I did not meet her again in the years after our long ago encounter but I learned news of her from Devaki. Shortly before Kamaladevi’s death, she was to be the chief guest at the Platinum Jubilee of the All India Women’s Conference, which meant sitting on the podium along with other “dignitaries” in a huge convention hall to receive an award. Kamaladevi refused and sat in the last row of the hall bringing the rush of photographers, journalists and VIPs to the back. Why? Because she wanted to reverse the hierarchy in the room.

In The Bible, Jesus tells the disciples that when entering the Kingdom of Heaven, “the last shall be first, and the first last….” I doubt that Kamaladevi had Jesus in mind when she shared that democratic purpose. She wasn’t waiting for heaven. She was doing it herself.

We do what we see more than what we are told. There is no telling what we may do once we know Kamaladevi.

(This is an edited version of the foreword she has written for A Passionate Life; Writings by and on Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay Edited by Ellen Carol Dubois and Vinay Lal | Zubaan | Rs 995 | 483 pages)

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

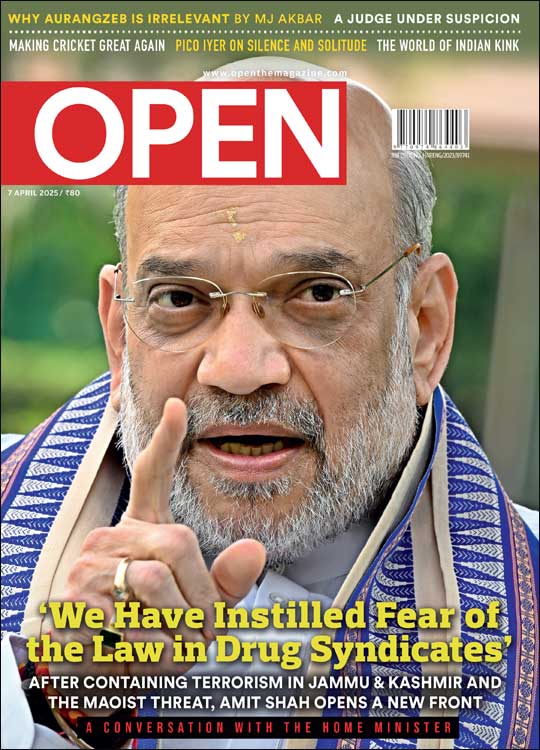

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

Elon Musk attracts sharp attack over ‘swastika’ from Indians on social media Ullekh NP

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh

Why CSK Fans Are Angry With ‘Thala’ Dhoni Short Post