When Something Works

As with her first collection of poems, Tishani Doshi's best poems here are those in which a female experience, located boldly in the body, works as a comment on something larger

Short poems ('lyric' doesn't suffice anymore) are like a good joke, in which everything has to revolve around the punch line. This makes them the simplest and most difficult of genres, demanding not just the right choice of words (and silence), but perfect 'delivery', exact nuance, and a good idea of the reader's response. Unlike a good joke, though, a short poem that works needs to evoke more than laughter: it can evoke laughter, sadness, thought, beauty and a dozen other emotions and responses, usually in apt combinations.

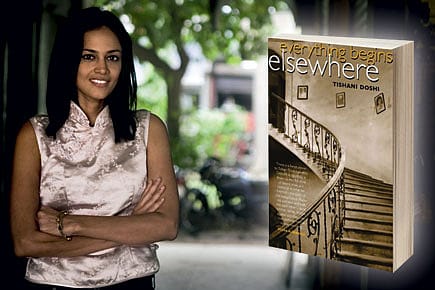

We know from her first collection, the prize-winning Countries of the Body, that Tishani Doshi can do so. In that collection, Doshi had sculpted a song of longing and loss, and a beautiful evocation of the female body, that worked as a comment on not just life, but existence. The best poems of her second collection, Everything Begins Elsewhere, are also those in which a gendered experience, located beautifully and boldly in the body, moves the reader's thoughts in 'different directions', as Adam Zagajewski puts it in his blurb: towards 'joy and sadness, praise and lament, love and disenchantment—simultaneously'.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Doshi writes with a consciousness of form; she has the capacity, rare in Indian poetry in English, to use nuances without getting lost in vacuity, to rework personal perceptions into something that can hold meaning for others. In this book too, she is at her best in poems like Sunday Afternoon and Lost, where she largely traces the areas covered by her in her debut collection:

'… the ocean that travels with me; how it / gathers and breaks, / gathers and breaks: like love, how it / stills, then parts.' / (Lesson 2: Learning Mudras in Bhutan)

There are also poems, like Memory of Wales, where she recuperates and annotates memories as effectively as she did in her first collection.

But Doshi is not a one-book wonder; this collection shows a desire to strike off in other directions too. As is the case with most second collections by talented and ambitious poets, this desire sometimes leads to her stumbling in the dark. This, in Doshi's case, happens when she tries to move on to a direct and gritty detail of life outside the spheres of her felt experience, as in poems like Evening on an Indian Railway Platform or Michael Mangal's Dream.

In the five to six poems that did not really work for me, I felt Doshi straining at the leashes of both her creativity and her life. This is not really a criticism. As an effort, it is commendable. But it exposes her to new dangers, and sometimes her poetry shows the strain of the effort. Even here, though, she has some remarkable successes, as in poems like Buffaloes and Lesson 6: How Not To Age.

In the latter poem, she bases her description of another person and life in a milieu she knows well and feels comfortable in. This works. And in Buffaloes, she uses the dense reality of water buffaloes on the streets outside her poems to develop a personal and experiential perception:

'…When I see buffaloes run / I think of love—how it is held / in the meaty, muscled pink / of the tongue: how quickly / it is beaten from us—/ all that brute resolve disappearing / in the undergrowth.'

Am I saying that Doshi's poems work best when they are rooted in the particular? Not really, for I am quite tired of statements about how literature has to do with the particular. This is one of those mantras that Romantics have handed on to us. It is only partly useful; anyone from Milton to Dryden, Kalidas to Kabir would have had trouble accepting it verbatim. It is true that these days it is fashionable to focus on the particular, while, for neo-classicists (for instance), it was fashionable to concentrate on the general: 'what oft was thought but never so well expressed'. Actually, Doshi's best poems are rooted in a particular experience or sentiment but always hint at something larger, more general. Finally, like any good writer, she maintains her own distinctive balance between the particular and the general.