The First Reels

A MAN, SERIOUS IN BLACK and white, stares pensively, a pipe tucked between his fingers, the shadow of a film camera looming behind him. This is Josef Wirsching, a German immigrant to India, and one of the pioneering cinematographers of early Bombay cinema. This photo is one of thousands preserved from Wirsching’s personal collection, now on display at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Mumbai, till April 17. A Cinematic Imagination: Josef Wirsching and the Bombay Talkies is a collaboration between the museum, the Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation and the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts.

Wirsching is in some of these photos, but more than the man himself, the collection captures a pivotal period in cinematic history: from the time the talkies were introduced until a little after independence. The photos are rich and varied: from behind-the-scenes peaks of stars relaxing, to sumptuous lobby cards used during movie premieres to recce shots, to scenes of filming in progress. The exhibition draws on a personal collection amassed between the 1920s to the 1960s, many shot in 35mm using a Leica camera.

“You can see the apparatus of cinema stand revealed,” says Debashree Mukherjee, one of the curators of the exhibition, and an associate professor of film and media at Columbia University, New York. “For someone like me who’s interested in the material practice of cinema, it’s quite a shock and delight to see that. You also get a sense of life on a set… a texture of everyday life at work in the movies.”

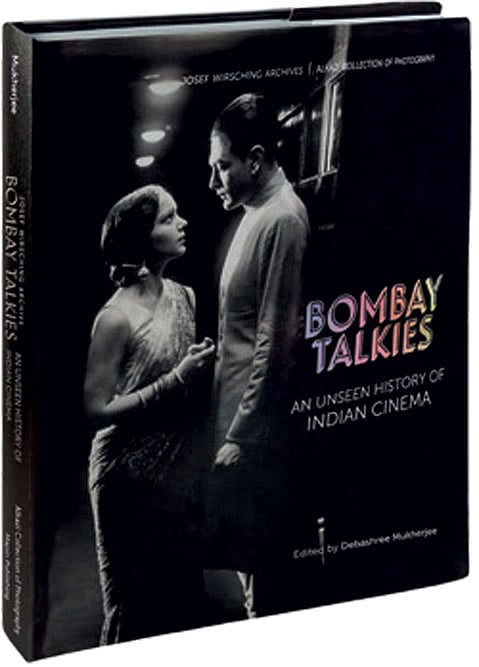

Mukherjee stumbled on this collection when she first contacted the Wirsching family more than a decade ago during her PhD. She has also edited a lush volume, which released this month, featuring the photos and scholarly essays: Bombay Talkies: An Unseen History of Indian Cinema (Mapin; 196 pages; ₹3,950). It was launched alongside the exhibition. In her introduction, she writes: “These photographs, most of them taken on film sets and outdoor locations, show us a world of meaning that was never intended to be projected on the silver screen. These behind-the-scenes photographs add new layers to how we understand cinema and the past.”

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

This is especially significant since so little survives from that period. “The first thing that someone who is trying to work on this history encounters is an acute lack of any archival primary sources,” says Mukherjee. “The archive of Indian cinema is very fragmented, and very fragile.” Most films from the pre-independence period are considered “lost”, with no hope of seeing them, let alone understanding the wider contexts in which they were created. So how did Wirsching even end up in India, documenting the early days of a new industry?

Josef Wirsching was born in Munich in 1903 to a father who ran a set design and costumes business. He fell in love with the camera at a young age, and studied photography before joining Emelka Film Studios in 1923. Movies were very much in their infancy then—the first talkie was only released in 1927. As Nazism took hold of Germany in the 1930s, Wirsching was growing increasingly disenchanted. By this time, a young lawyer from India called Himanshu Rai was in the process of setting up a film studio in Bombay. He had previously collaborated with Wirsching and other German colleagues, so it was only natural that he sought their technical and creative support. The director Frans Osten and Wirsching decided to grab this new opportunity and move east. They joined Bombay Talkies, the new venture of Rai, and his wife, the future star Devika Rani. The studio’s first film Jawani ki Hawa released in 1935.

“The fact that there were Germans working with one of the most trendsetting studios of Bombay cinema is very interesting,” says Mukherjee. “Because it helps to question or unsettle ideas of what is Indian about Indian cinema. Where does one go to establish authenticity? We can’t even say if it’s nationality or ethnicity that determines the early years of Indian cinema coming into being.”

The early talkies, like the ones Bombay Talkies was producing, came in a moment of ferment. The Germans brought their cinematic idiom— expressionism—to an industry in search of an identity.

“There was nothing really to adapt to [for them]. They were part of the flux of the emergence of this aesthetic form, right?” says Mukherjee. “Which is why Wirsching, Osten have a very pioneering role, because together they are participating in the emergence of something that we will later be able to say is a distinctive form, that is Indian cinema.”

Bombay Talkies wasn’t just a trans-national melting pot— it became a trans-regional, subcontinental affair. Writers, technicians and artists came in from Lucknow, Lahore, Bengal, Gujarat and Kashmir. As the silent era gave way to the talking pictures, these practitioners were grappling with questions like, how should dialogues be written? In what language? Should there be songs? What kind?

Bombay Talkies went on to feature major stars such as Ashok Kumar, Dilip Kumar, Madhubala and Meena Kumari. Its films tended to be love stories, interspersed with songs, or “socials”, films that focussed on socio-economic conditions.

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Wirsching was interned as an “enemy alien” in prisoner-of-war-camps along with other Germans living in British India. He was reunited with his family in 1944. But having fallen in love with the country, he never went back to live in Germany. Once Bombay Talkies shut in 1953, he worked on other projects. His last film was Pakeezah, which had not yet been completed when he died in 1967. His son Peter looked after the collection for decades, even as the family moved cities. Peter’s son Georg, always knew his grandfather had been a legendary cinematographer in the early days of Bombay cinema. But it wasn’t until he studied visual arts himself, as a teenager, that his grandfather’s work really hit him. For decades, the family had preserved Wirsching’s metallic trunks packed with negatives in canisters and printed photos and lobby cards. In 2009, when the family relocated to Goa, Georg began to unpack and rediscover what these boxes held. Most were in immaculate condition, several had labels and captions.

“If you look at [the prints] they are in such perfect condition, and that’s how my grandfather packed them and how my dad maintained them for so many years,” says Georg. He spent the next two years studying and cataloguing the collection.

“My grandfather was famous for his ability to paint with light, so to speak,” says Georg. “He was solely the man responsible for literally making Devika Rani, Meena Kumari, all of these actresses even more beautiful and desirable on screen.”

In his photos, they smile, they preen, they stare, sometimes cognisant of the watching camera, at other times they are caught in moments of spontaneity.

Georg scanned, catalogued and documented hundreds of photos in the collection—including negatives—starting in 2009. He has also rendered some of these photos in his own work as an artist, through charcoal drawings and paintings.

Over time, the Alkazi Foundation became a part of the effort, and has been involved in organising exhibitions. Versions of the exhibition have already been shown in Goa, Chennai and Delhi. But the Mumbai exhibition is special; after all that’s where Wirsching worked. “Essentially all of this material originated in Bombay, so it would have been remiss if it had not come here, the exhibition had to come to its home,” says Georg. “It’s a dream come true. I only wish my dad had been alive to see this happen.” The value of such a collection speaks for itself. Mukherjee says one of the surprising, or counterintuitive discoveries for her, was to see certain simplistic notions of the industry collapse.

“One of the big things that gets disrupted is this mythology of a completely disorganised cottage industry, which was based on some kind of joint family model,” she says. “The 1930s were clearly a time when Bombay Talkies and other studios really privileged a lot of pre-production work. They really worked hard on the scripting, in order to streamline production, in order to roll out four to five films a year, which doesn’t happen out of chaos.”

The exhibition will likely be shown in other cities, though details have yet to be finalised. In the meanwhile, Georg is also working on a book, drawing from the family archive.

(A Cinematic Imagination: Josef Wirsching and the Bombay Talkies is on display at Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Mumbai, till April 17)