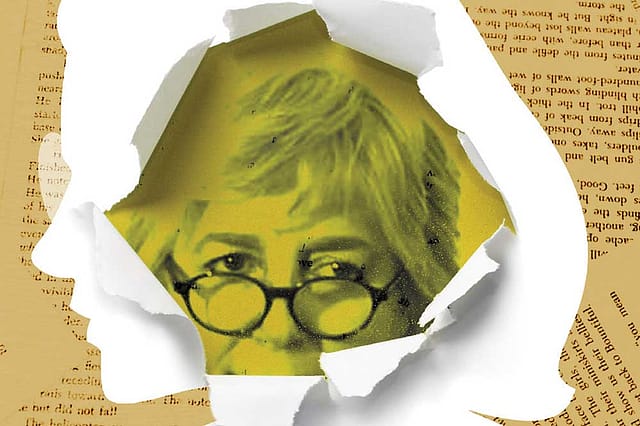

The Name of the Author

ELENA FERRANTE IS easily one of the greatest literary enigmas of our time. The Italian author, first published in Italy in 1992, and best known for her Neapolitan quartet, has become a sensation over the past few years. Time included her in its list of the 100 Most Influential People of 2016. Ferrante has sold over 2.6 million English language books (translated by Ann Goldstein) in the West. While the sharpness of her prose and the acuity of the emotions is undisputed, her biography has remained a mystery. Edizione E/O, the Rome-based publishing house that brings out her work, refuses to divulge any details. The few interviews she has given in recent years have been through her publishers and over email.

Early this week, the literary world was thrown into a tizzy when a blog post published by The New York Review of Books alleged that the ‘true identity’ of Elena Ferrante had been uncovered. Investigative journalist Claudio Gatti writes, ‘After a months-long investigation it is now possible to make a powerful case for Ferrante’s true identity. Far from the daughter of a Neapolitan seamstress described in Frantumaglia [An Author’s Journey Told Through Letters, Interviews and Occasional Writings, to be published in English next month], new revelations from the real estate and financial records point to Anita Raja, a Rome-based translator whose German-born mother fled the Holocaust and later married a Neapolitan magistrate.’

Braving the Bad New World

13 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 62

National interest guides Modi as he navigates the Middle East conflict and the oil crisis

While Gatti might be congratulating himself for this journalist scoop, Ferrante’s readers couldn’t care less. In this age of overexposure and self- marketing, Ferrante was (is) the readers’ ultimate writer. Today authors feel compelled to sell their work as much as their biographies. Marketing has become the midwife of storytelling. Authors lay the blame for the machinations of self-promotions on publishers, and publishers fob off responsibility on readers’ demands. But Ferrante did the impossible. She set her novels free into the world and did not follow them with either leash or pom-poms. Of course, it is testimony of the brilliance of her novels that they won over readers and critics alike, without the brouhaha of the publicity machinery.

In 2014 David Zweig wrote a book titled Invisibles: The Power of Anonymous Work in an Age of Relentless Self-Promotion. Ferrante is the consummate Invisible, and she must be hailed for it.

Zweig explains, ‘For [Invisibles], any time spent courting praise or fame is time taken away from the important and interesting work at hand...The better they do their jobs, the more they disappear.’ Similarly, for Ferrante the ‘demand for self-promotion diminishes the actual work of art’. Zweig says Invisibles prefer to use ‘we’ and not ‘I’, when talking about their work. Similarly, Ferrante says in an interview with The Paris Review, ‘The media simply can’t discuss a work of literature without pointing to some writer-hero. And yet there is no work of literature that is not the fruit of tradition, of many skills, of a sort of collective intelligence. We wrongfully diminish this collective intelligence when we insist on there being a single protagonist behind every work of art.’

Gatti fails to recognise this. Ferrante’s work reflects a ‘collective intelligence’, freed from the tyranny of the individual. Today the public is witness only to ‘manufactured images’ and not the truth.

For Ferrante, there is only one truth. And that is the ‘literary truth’ of the pitch-perfect sentence. For her, the reader is not a consumer to be indulged, but a listener who she wrings out with her stories. For fans of Ferrante’s work and those who love literature, her books are enough. Nothing else matters.