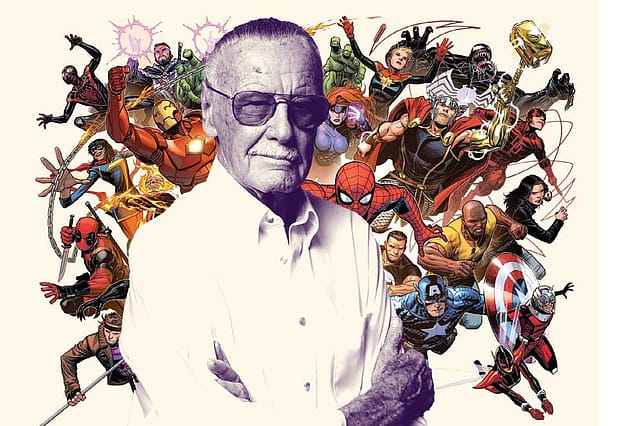

Stan Lee (1922-2018): Such a Marvel

WHEN ONE NEEDS to appraise the work of a novelist, we often take a bifocal view of the author. One is the writer. A towering talent hunched over a desk, uninterested in the grease and grime of commerce and formula, but someone engaged in the true pursuit of art, pouring himself on to the page, willing to even risk producing difficult- to-read works (at least for casual readers). And then there is the storyteller. Someone more interested in a story than in his voice, who is constantly perceived to be punching above his literary weight. These are of course not neat categories. All novelists write stories. Great writers tell equally good stories and great storytellers write equally good sentences. But implicit in this categorisation is the notion of the ‘storyteller’ being the lesser artist.

A few years ago, The Guardian reached for the appelation of ‘storyteller’ to suggest that Stan Lee—the creator of Marvel Comics who died a few days ago—was one of the great tellers of stories in the post-War era. Unsurprisingly, several disagreed, pointing out how the superhero genre is nothing but a fad and how Lee’s work has little meaning beyond the world of a 12-year-old. For many, the comic book format has little or no artistic merit. To the extent there is an unwillingness to recognise the work of a person who created a universe of characters that are among the best recognised in recent history.

2026 Forecast

09 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 53

What to read and watch this year

There is reason to argue that Lee is one of the greats of recent times. He has had such an outsized influence on contemporary culture, spanning not just the comic book format but even the movie and television industry. He created what is arguably the most popular cultural product of a century. Lee created, or co-created, the modern comic book superhero and the template of the blockbuster film. He created characters that are larger than the movie superstars who don their costumes. When we go to watch an Iron Man or an X-Men film, we don’t go to watch Robert Downey Jr or Hugh Jackman; we go to watch Iron Man and Wolverine, the superheroes.

Lee, born Stanley Martin Lieber in 1922 in New York, started work when he was 17 at a publishing house that brought out comics. By his claim, he took the name Stan Lee because he was “saving his real name” for the Great American Novel he planned to write, but many have suggested he wanted a less ‘ethnic-sounding’ name.

Before Lee, superheroes in comic books were boring, stodgy figures. Lee injected a wild inventiveness and human depth into them. He gave them complex emotional lives, from a boy who fought off super-villains while worrying about his grades and acne (Spiderman) to a self-loathing monster (The Hulk). He borrowed stories and themes from around him, from Norse mythology to the Cold War, and set them in real places.

There is of course some dispute over the role Lee really played in creating some of these characters. Lee collaborated with a number of great artists. The family of one of them, Jack Kirby, for instance, won a multimillion dollar settlement after which Kirby was credited as a co-creator. According to Vanity Fair, ‘Instead of writing panel-by-panel scripts for artists to draw, [Lee] turned the work of pacing and staging, and often plotting, over to his collaborators. Sometimes he’d jump up on his desk to act out a scenario he’d envisioned; sometimes he’d simply offer a suggestion of who might appear in the next issue. After a story was drawn or at least penciled, he’d add text, sometimes elaborating on notes supplied by artists.’

Irrespective of the true origin of a few of his superheroes, Lee did have the vision of something larger than a comic strip as a home for them. It would take the 21st century for the movie industry’s special-effects to finally catch up with that vision.