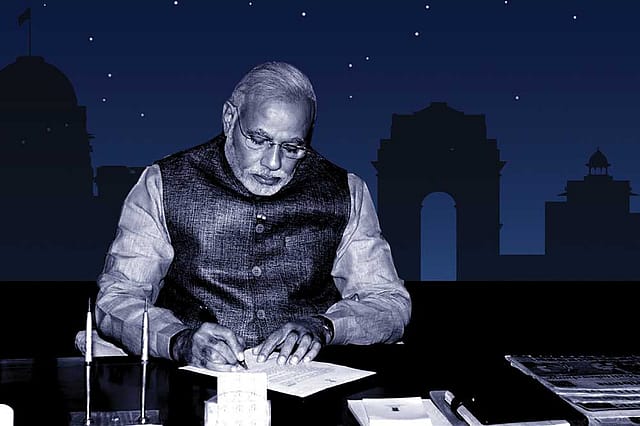

Sleepless in Power

PRIME MINISTER NARENDRA Modi’s three- hour sleep has become as much of a conversation starter as it has a meme, praised and mocked in equal measure. He joins a select group of world leaders who have worn their lack of sleep as a badge of honour. The late Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, good friends, were both proud functioning insomniacs, getting by on four hours of sleep. Barack Obama, the US president who famously asked Modi why he didn’t sleep for longer, slept for five hours a day, reading briefs and working till late in the night. His successor, Donald Trump, may not be as intellectually accomplished, but he sleeps for a mere three-to-four hours a day as well, sometimes as little as 90 minutes. He wakes up to a stack of morning papers where he has been mentioned, which is enough to give him an adrenalin boost to kickstart his day.

Sleep has become a modern luxury, often sacrificed for working late into the night, and rising early. What was considered a war time necessity, getting soldiers to remain alert even with a few hours of sleep, has become a global quest across all professions, with a few biotech companies working on serious innovations to eliminate sleep. From the use of dexedrine to keep soldiers awake during the First World War, there has been much evolution. Among other things, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the research arm of the US military, has developed a mask called the Somneo Sleep Trainer that exploits one- or two-hour windows for strategic naps in mobile sleeping environments, screening out ambient noise and visual distractions while Duke University neuroscientists have been using Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) to induce slow-wave oscillations, the once-per-second ripples of brain activity seen in deep sleep, shrinking eight hours of sleep into four.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Equally though wellness companies are working to make everyone sleep more and better. Arianna Huffington has written an entire book about her brush with no sleep which resulted in her falling face first on her desk in a pool of blood. Conventional wisdom insists that too little sleep is bad for one’s health—and the Supreme Court of India even declared in 2012 that the Right to Sleep is a fundamental right. After all, sleep deprivation is an effective form of torture.

But it turns out that the one percent elite, the world’s most famous people, past and present, sleep only between 1 am and 4 am. Thomas Edison considered sleep a waste of time because he got his best ideas at night. Leonardo da Vinci took 20 minute naps every four hours, in something called the Uberman sleep cycle. Winston Churchill slept for two hours at 5 pm every day. Although most people need at least seven hours of sleep each night, research has found a genetic mutation in the p.Tyr362HIS, a variant of the BHLHE41 gene, that allows some people to sleep less and still have brains that function well after periods of sleep deprivation.

Sleep, sleep disturbances and how they affect people, especially young peoples’ mental health and development, are issues that we grapple with all the time, says well known psychiatrist Dr Amit Sen. The problem is exacerbated with the increasing use of technology. It is also leading to a new genre of specialists, the sleep evangelists. One of them, Matthew Walker, neuroscientist at the University of California, Berkeley, writes in his new book Why We Sleep, that a good night’s sleep is the best bridge between hope and despair. And this is not mere sentiment, but backed by science that indicates that after 16 hours of being awake, the brain begins to fail. Humans, he writes, need more than seven hours of sleep each night to maintain cognitive performance. After ten days of just seven hours of sleep, the brain is as dysfunctional as it would be after going without sleep for twenty-four hours. Three full nights of recovery sleep are insufficient to restore performance back to normal levels after a week of short sleeping, he writes.

He also makes an interesting point related to too little sleep across the adult life span significantly raising the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. ‘Parenthetically, and unscientifically, I have always found it curious that Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan—two heads of state that were very vocal, if not proud, about sleeping only four to five hours a night—both went on to develop the ruthless disease,’ Walker writes.

But that is for ordinary people. Extraordinarily driven people like Modi have a different standard. In 2012 at a Google Plus hangout anchored by actor Ajay Devgn, Modi said he was a workaholic, who slept three to four hours a day. “Within 30 seconds of my head hitting the pillow, it is sound sleep,’’ he said. Mornings are all about yoga and pranayama. Compare that to Rahul Gandhi’s more routine pattern of six hours of sleep, waking up before six, followed by a run or exercise in the gym.

The debate about sleep is essentially a debate on the nature of modern work and the new professional who is never switched off. Reagan, for instance, may have slept little, but he stuck to a fixed routine, working in the Oval Office between 9 am and 6.30 pm, impossible now in the world of constant social media updates and round the clock emails. Do people prefer a politician who works 24x7, 365 days a year, without taking a holiday and sleeping little, or the politician who sees no shame in taking vacations, considers listening to people and introspecting part of his work, and does not believe in sleep deprivation oneupmanship? While Rahul Gandhi said recently that he does not consider not sleeping to be a measure of working, Modi has lost no opportunity to showcase himself as someone who works 18 hours a day and never takes a day off. The contrast before the nation is said to be clear: the permanent campaigner vs the part-time politician; the doer vs the philosopher; the kaamdar vs the naamdar. That is before Challenger Rahul started contesting for the same media space as Candidate Modi, rally for rally, interview for interview.

Back in the day in 2014 when Rahul Gandhi was still referred to as Pappu on social media, a photograph of him sleeping in the Lok Sabha went viral on social media. Comparisons were made with HD Deve Gowda, the ‘humble farmer’ who became India’s 11th prime minister, and would often be caught snoozing, enough for cartoonist RK Laxman to immortalise him as the Sleeping Prime Minister. Sleeping on the job is not great optics, except perhaps in Japan, where it has a name, inemuri, which roughly translates to ‘sleeping while present’, and is seen as a positive, a sign of exhaustion caused by hard work.

Arianna Huffington, one of the leading advocates of The Sleep Revolution, also the name of her 2018 bestseller, has made sleep a mini-industry. Her six tips? Put your phone and laptop to bed half-hour before you; take a hot bath with Epsom salts before bed; change into nightwear; keep your bedroom dark, quiet and cool like a ‘slumber palace’; avoid caffeine and don’t use your bed for anything other than sleep (and sex, if you can get it).

And if you have any doubt that sleep is as much personal as it is political, you only have to see how the Right to Sleep came about—in a judgment that said police action against a sleeping crowd at Baba Ramdev’s 2012 rally in Ramlila Grounds was wrong and against Article 21 of the Constitution.