Double Malt

IN AN OLD TV ad, a young son guzzles half a glass of Horlicks and runs out to catch his school bus. Standard late 80s and 90s advertising fare. But, according to Sandeep Goyal, an executive working on the ad, as revealed in a recent newspaper column, the brand team was besieged with furious complaints when it was aired. They had overlooked something. But when it comes to iconic brands, especially those marketed as essential to something as sensitive as children’s health, these seemingly small details can never really be that small. On the other end were angry mothers from across the country demanding to know why the glass in the ad had not been finished. This sent a wrong signal to children, they argued. Their children’s nutrition would suffer. So now a new section had to be shot. The boy had to be called back before he boarded the bus. And he now had to finish his entire glass of Horlicks.

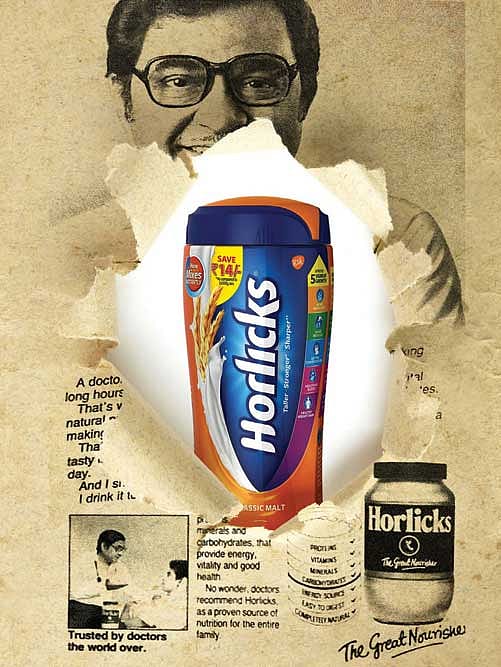

If India ever had a national drink, a glass of milk with Horlicks would have a good shot at it. The brand is now changing hands, as Hindustan Unilever buys the consumer-products business of GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare, which used to make and market Horlicks, in a deal estimated at Rs 31,700 crore.

Started in the 1860s by two brothers from Gloucestershire in England—James and William Horlick were experimenting with a nutritional supplement derived from malted barley for infants— Horlicks was aimed at an international market. Soldiers carried it to war. Expeditionists famously carried it to the North and South Poles. In India, it is believed to have first come in the backpacks of Indian soldiers in the British army returning from World War I; they had gotten accustomed to it during the war. Once here, its popularity as a family drink spread among affluent Indians.

2025 In Review

12 Dec 2025 - Vol 04 | Issue 51

Words and scenes in retrospect

While the market for nutritional supplements was declining globally, Horlicks was to become hugely popular in India—not just as a milk additive, but also as a substitute in milk-deficient parts of the country (and among the lactose-intolerant). Even as its health benefits were coming under doubt elsewhere, here mothers carried home a jar of Horlicks with their monthly rations. They gifted it to convalescing relatives or friends. And few sights gave them as much satisfaction as their children at the breakfast table—and preferably also before turning into bed—gulping down Horlicks. Children had another incentive: invariably at the bottom of the glass would be sweet unmixed lumps that had escaped their mothers and could be spooned out.

Horlicks became so popular here as it tapped one of Indian mothers’ biggest fears: that their children would be undernourished. Undernourishment was—and still is—a serious issue in India, as also the risk of milk adulteration. The other big fear was their children might get left behind in India’s competitive education system; that somewhere in the exams lined up for them throughout their childhood and adolescence—from kindergarten to civil services and engineering colleges—they would slip. A childhood of tuition and coaching classes plus Horlicks with milk seemed to be a good formula to assuage such fears.

However, Horlicks’ growth is slowing here too. According to Mint, after a decade of double-digit growth, sales in India rose just 8.6 per cent in 2017 and could drop to half that rate this year. By 2022, Euromonitor claims, the market will expand by 2.7 per cent. People are becoming more conscious and aware that while Horlicks may have nutrients and protein, it also contains large amounts of carbohydrates and—that modern-day evil—sugar.

Unilever, no doubt, has ideas of its own. And its extensive distribution channels in even the smallest towns of India might give Horlicks a boost.