BV Doshi: Outlining Lives

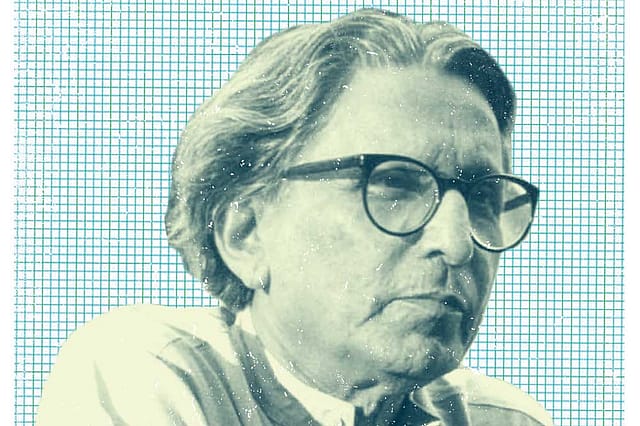

“ARCHITECTURE IS A backdrop for life,” was how the architect BV Doshi or Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi described his philosophy of design in a recent interview. A Padmashree recipient and a living legend in Indian architecture, 90-year-old Doshi has been hooured with what’s often referred to as the Nobel for architects, the Pritzker Architecture Prize.

Doshi started studying architecture in 1947 and was part of the country’s first generation of post-independence architects. As against its overwhelming commercial nature today, the discipline in the early years of the country, ably supported by the state, saw a different role for itself. Architects were expected to shape the country. Through their designs and concepts, it was hoped they would reflect and evoke Indian culture and history.

Over the course of seven decades, Doshi has lived up to that lofty ideal. He became not just an architect, but also an urban planner, a teacher and an institution builder. He became a pioneer of low-income housing projects. He built one such in Indore, Aranya Low Cost Housing, for which he was awarded the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, where around 80,000 low and middle-income residents now live in homes with shared courtyards and a maze of internal pathways. He helped create Chandigarh. He designed the Indian Institute of Managements in Bengaluru and Lucknow, New Delhi’s National Institute of Fashion Technology, the Tagore Memorial Hall in Ahmedabad, and a number of other institutional buildings. Doshi worked with and was mentored by two of the great Modernists of the 20th century—Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn. Doshi likes to say that he believes Le Corbusier, the chief architect of Chandigarh, still watches over him, and this ensures that he does not imitate or repeat a design. After the Pritzker Architecture Prize was awarded to him, he responded in a press statement that he owes the prize to Le Corbusier. “His teachings led me to question identity and compelled me to discover new regionally adopted contemporary expressions for a sustainable holistic habitat,” Doshi said. A newspaper article reported how once Doshi pointed towards a photo of Le Corbusier, which he places alongside Goddess Durga and Lord Ganesha at the entrance of his office cabin, to a journalist, and said that he thanks them whenever he leaves or enters his office. “They ask me questions. I hold a silent dialogue with them. They are there,” he told her.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Apart from Le Corbusier, a major source of Doshi’s inspiration came from the humble family of carpenters and furniture-makers that he was born into and the house he shared with them in his early life. He acquired his need for perfection, the need to constantly tweak and rework even for seemingly insignificant improvements from his grandfather, as he often says in interviews. His grandfather ran a furniture workshop, and the young Doshi grew up with the odour of wood shavings and lacquer. The house that he was born in was an ever-expanding place. New levels would be repeatedly added as the joint family expanded.

“I always sensed the space as alive. Space and light and the kind of movement that gets into the space for me are very, very significant. That’s what generates a dialogue. That’s what generates activities. And that’s where you begin to become part of life,” he told National Public Radio recently.

Doshi belongs to that small group of architects who changed the discourse of architecture in post- independence India, whose works were underlined by a philosophy and culture, their forms not external, as a part of real estate but far more integral—as a backdrop to life itself.