VO Chidambaram Pillai: Patriot of the Seas

A TAMIL HERO HAILED AS kappalottiya Tamizhan (the great Tamil helmsman) and chekkizhutha semmal (the noble man who pulled the oil mill–in prison), VO Chidambaram Pillai (1872-1936) was the nucleus of the Swadeshi Movement in Madras Presidency. Conceived against all odds in 1906, his venture, the Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company (SSNCo), directly competed against the world’s largest shipping company at the time—the British India Steam Navigation Company, which, backed by the colonial government, controlled maritime trade in the region. The first large-scale attempt to challenge the foreign monopoly of Indian waterways, the SSNCo took on entrenched frameworks of power and greed, steered by the imagination of a better tomorrow. And for a while, it gave patriots hope. In fact, swadeshi ships started moving the entire cargo from Tuticorin to Colombo, leaving the British empire seething at the loss of business. The British administration subsequently cracked down on swadeshis including VO Chidambaram Pillai (VOC) and the nationalist-poet Subramania Bharati, charging them with sedition and incapacitating them—but not without sustaining human and material losses themselves. In June 1911, Robert William D’escourt Ashe, the acting district magistrate of Tirunelveli district who had earned the wrath of locals for his actions against the SSNCo, was assassinated by a revolutionary named Vanchinathan, in an apparent act of revenge.

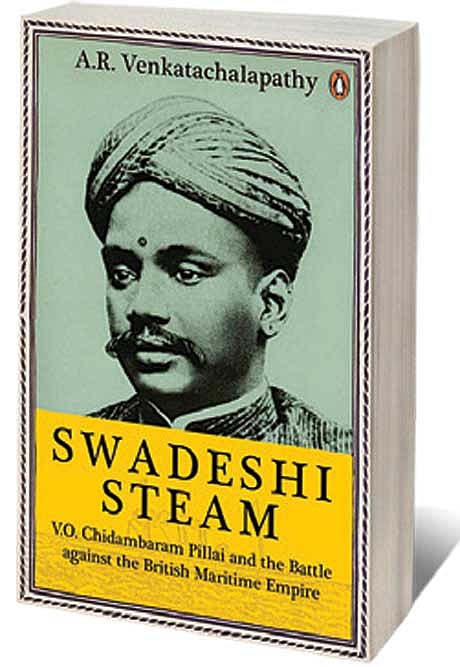

The SSNCo was VOC’s labour of love, and it cost him dearly, as he was also a labour leader and a convincing swadeshi campaigner who was on the watchlist for his tendentious speeches—especially upon his return from the 1907 Congress session held in Surat. But how did VOC pull it off? Historian AR Venkatachalapathy has spent the last 40 years tracking all surviving material on VOC and published seven books in Tamil on him, one containing 18 hitherto unpublished letters exchanged between VOC and Gandhi. He now offers a blow-by-blow account of how the company came into being despite the struggle to raise funds and buy steamers, and how it functioned in a hostile environment, with a foreign competitor slashing rates and luring merchants with perks, including clothes. Swadeshi Steam is the first account published in English of a resourceful and resilient man taking on the British Empire and igniting the fire of nationalism in Tuticorin. VOC, a small-town pleader who decides to start a shipping company that would not just challenge colonial mercantile interests but also make a bold swadeshi statement, makes for an unforgettable protagonist. “As a key figure in the Tilak camp of the Indian National Congress, he drew national attention to the company through his political engagement... VOC mobilized people by employing the Tamil language for political communication—a novelty until then. Both share capital for the shipping company and political capital for the freedom struggle were accumulated thus. In this process, VOC eclipsed a pantheon of earlier moderate leaders and emerged as the new face of nationalism in south India, and its first mass leader,” Venkatachalapathy writes.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Conviction shaped VOC into a leading revolutionary, even if he is not recognised as one outside of Tamil Nadu today. “While studying in Class 9 in a CBSE school, I was dumbfounded that there was no mention at all of VOC in the history textbooks. The situation hasn’t changed much in the four decades since,” recalls Venkatachalapathy. Always fascinated by biographies, he even now remembers “a big biography of Baden-Powell, the founder of the scout movement.” However, when he searched for biographies of Indian—especially Tamil—personalities “the cupboard was sparse,” says Venkatachalapathy. VOC seemed a hero to him, and he resolved to fill the gap and write about him. After finding a bunch of unpublished letters of VOC in the Maraimalai Adigal Library in Chennai, he spent years gathering more. Swadeshi Steam is based on these letters, on maritime records, on VOC’s own memoir, on interviews with his family, and on newspapers—including the correspondence columns, which the author has sifted through for public opinion. In fact, the book offers a fascinating account of journalism in early-20th-century Madras, revealing the blinding admiration of the nationalist press at how an unlikely shipping startup had become every Indian nationalist’s pride and joy. In 1906, when talk of floating a shipping company with a share capital of Rs 5 lakh divided into 10,000 shares was mooted, a correspondent “brimmed with optimism when he wrote that given the ‘good deal of patriotism and Swadeshi spirit manifest at Tuticorin’ it would not be long before the entire capital would be subscribed,” the author writes. When the SSNCo’s steamers, the Gallia and the Lawoe, finally arrived after long delays, Bharati welcomed them with a cartoon, likening “India’s joy to that of a mother being suddenly blessed with two children after a long period of barrenness”. “Swadeshi was SSNCo’s oxygen, lifeblood, ballast, steam, its raison d’etre,” writes Venkatachalapathy. The reader is transported into the thick of that time, as though watching unedited footage—dozens of employees and agents fanning out on fundraising tours, the hectic campaigning in Tuticorin, the balancing of books, letters flying back and forth urging friends and family to subscribe to shares.

The poetic idealism would subside, however, as the SSNCo was being “tossed about in choppy waters and was finally grounded in a tragic story”. The story is doubly tragic because VOC was in prison at the time, serving an unreasonably harsh sentence—two life terms, later commuted to six years in prison and four years in transportation, running concurrently. “When he launched the Swadeshi company, VOC was a young man of thirty-four with a flourishing practice and a growing family. Two years later, he was arraigned for sedition and languished in prison for nearly five years, undergoing the harshest punishment,” Venkatachalapathy writes.

At a time when India, having built its first indigenous aircraft carrier INS Vikrant, is keen to be seen as a major maritime power, there can be little doubt that VOC deserves an entire biography. “I focused on VOC’s one great achievement, the swadeshi shipping company. I hope to write at least three more volumes in English covering his entire life in the hope that Swadeshi Steam will kindle interest in VOC,” Venkatachalapathy says. To him, VOC is not just an academic project. “I started my search for VOC as a boy and have lived with him for over four decades. But for VOC, I would not have become a historian in the first place.” While looking for information on VOC, he unearthed and published original material about Tamil Nadu in the colonial period, writing entire works on key figures like Bharati, journalist AK Chettiar and Ashe, the only British official to be assassinated during the freedom struggle in south India. He is also working on a biography of Periyar—again, after encountering him in context with VOC—trying to “marry the narration of his political life with the development of his ideas.”

In Swadeshi Steam, Venkatachalapathy delves into the personal histories of the many directors of the company and other associates of VOC, tracking down documentation and even their descendants—many of whom had no idea about their involvement in SSNCo. No incident is superfluous to the historian, and one can tell that he has lost sleep trying to tie up many loose ends in the absence of any surviving documentation; who, for instance, was S Vedamurthi Mudaliar, the mysterious man VOC entrusted with inspecting the ships in Marseilles, who later fell out with him as the vessels kept breaking down? Venkatachalapathy’s account of VOC’s diligence as an entrepreneur, and his restraint when dealing with the foreign administration, breaks the stereotype perpetuated by those in the opposite camp of a fiery swadeshi who was not a level-headed businessman. “He was uncompromising and had much foresight. For instance, the prospectus for the SSNCo talks of plans to train Indian youth in navigation and to build dockyards and shipbuilding yards,” Venkatachalapathy says. Interestingly, he notes that VOC and his peers never mentioned the Cholas and their maritime history because they didn’t know about it, although it is common knowledge now. “That is the quirk of history. It has a strange way of going underground and resurfacing unexpectedly. The present always has a direct bearing on how the past is viewed,” says Venkatachalapathy.

It takes a committed historian to piece together stories like VOC’s without nostalgic exaggeration. Writing in narrative bursts and sparing no detail, the author demands our attention, lest we lose track of the vast cast of characters that populate the book. This is serious history, a dam against the ever-rising flood of social media fictions about long-lost personalities. Swadeshi Steam is a book that never runs out of steam, its driving force being the same as that of the author’s academic career—a fin-de-siecle revolutionary from Tuticorin and his faith in human potential.