The Prison Diarist

IT WAS AT the Byculla Women’s Jail in Mumbai, not long after she was being endearingly referred to as “Vakeel Aunty” for her willingness to write applications for bail and other requests for fellow inmates, when a sex worker recounted an amusing anecdote to Sudha Bharadwaj.

Bharadwaj turns her face to her right today, her head slightly bent, as she gathers this memory. She is dressed in a plain salwar kameez, her hair combed into a single plait. On a small stool beside her is a framed photograph of her daughter and her. Above on the wall, is a much larger and striking picture of her mentor, the trade union leader Shankar Guha Niyogi who was assassinated in 1991. As this memory comes to her, and the way the sex worker told it, a wide smile grows on her face.

“So, this girl was completely illiterate,” Bharadwaj says. “And whenever she had to save the number of a client on her phone, she would save it as an emoji based on the client’s profession or appearance.” When the sex worker was arrested, the policeman who had caught her had also snatched her phone, and now at the police station, he began to ring the contacts on her phone. “And guess what happened,” she recounts, “All over the police station, one after the other, phones started ringing. Many of the girl’s clients were policemen at that same station. The policeman began to say, ‘We have to transfer her case from here.’”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Bharadwaj’s laugh bellows across the hall of her small apartment in Borivali, Mumbai. Outside the window, night is falling rapidly, and the light from multiple apartment windows outline the shapes of the nearby high-rise buildings. Raising her hands, their fingers entwined with each other, she says, “Just shows you the nexus that’s there between the police and the crime, and just how normal this crime is.”

Bharadwaj, who was born into a family of academics in the US, appeared headed for a similar career path when she was studying in IIT Kanpur, but instead, she moved to Chhattisgarh, where she worked as a trade union activist and later a human rights lawyer as well. After spending several decades there, she relocated to Delhi in 2017 to take up what she calls her “first formal job” (that of a visiting professor at the National Law University), so she could provide for her daughter who would soon be entering college, when she found herself accused of inciting the caste-based violence that took place in Maharashtra’s Bhima Koregaon in 2018. She was picked up, along with several other scholars, activists and lawyers, for their alleged roles in the clash and for having links with Maoists, and jailed under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act [UAPA]. Bharadwaj was first incarcerated in Pune’s Yerawada Jail, and then transferred to Byculla Women’s Jail, before finally being released on bail more than three years after her arrest.

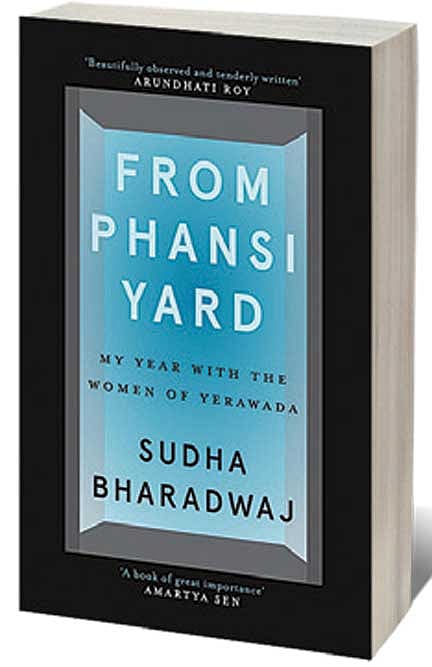

Her recent book From Phansi Yard: My Year with the Women of Yerawada (Juggernaut; 264 pages; ₹799) chronicles her time at the Pune jail. Bharadwaj had gotten accustomed to the rhythm of her new life—she even recalls thinking once, as she watched the inmates and their children go about their days, how a jail could at times resemble an ashram—when she was suddenly moved without explanation to the jail’s dreaded death row section. Here at ‘Phansi Yard’, with only three other inmates in adjoining cells— which included Shoma Sen, an activist and assistant professor at Nagpur University who had, like Bharadwaj, been accused of instigating the Bhima Koregaon violence, and two cantankerous sisters serving a death sentence for their involvement in a scandalous case around child trafficking and organ ‘harvesting’—Bharadwaj was kept in isolation. For the first time since her imprisonment, she felt overwhelmed. “The way I was taken there, without any explanation, and the way the bars just shut with a clang, and the powerlessness I felt. That I found very difficult,” she says.

Bharadwaj was lodged in a tiny cell, but it came with a view. Through the bars in the front and the window at the back, she could see the lawn where prisoners and children milled around and the factories where inmates worked at chores like rolling incense sticks and manufacturing small automobile parts. In this isolation, the 62-year-old activist wrote notes about the prison and its people. “I like putting myself in other people’s shoes,” Bharadwaj says. “I never wrote it thinking I would publish it. It was really just a way to understand the complex [stories] of how these women got here and how the criminal justice system treats them.”

From Phansi Yard is one of the most tender and illuminating accounts of prison life for women in India. A majority of the book consists of portraits of individuals she encountered. But there are also observations on jail life, from the way the class and caste system operate within bars for instance, to the authorities’ fears of lesbian relationships, to the quality of legal aid, to overcrowding, to reports about the food.

Each portrait or note usually consists of just a single page or two, or even less. No one is named because Bharadwaj wanted to protect their privacy. There are also no dates or chronology, because jail life, she says, is like a grindstone, just turning and turning, with an unchanging routine. “Observing women, listening to them, writing about them, and about life in a women’s jail, helped me,” she writes in the book. “This became my work. It gave me a sense of purpose. It calmed me. It helped me understand where I was, and didn’t leave any scope for self-pity.”

Bharadwaj writes about the inmates with great compassion and empathy. There are accounts of the children in these jails (children of women inmates are allowed to stay with them till the age of six, after which they are handed over to families outside or to an institution), old and infirm female prisoners, some even battling diseases like cancer or dealing with mental illnesses. There are accounts of women who seem to have gotten involved in cases because their husbands took the lead in committing the crime, some who appear to have gotten framed, and quite a few who Bharadwaj calls “judicial hostages”, or women who were arrested for their absconding husband’s crimes. (Their names are unfortunately tied to the crime, because, unknown to them, some of the proceeds of the crime were used to purchase items in their names.) Many inmates, of course, did commit crimes, some of them heinous, and Bharadwaj admits that it was at times difficult to reconcile the crime with the person who sat in front of her. “But I decided I would treat these women not as criminals but as human beings, and not approach them judgementally,” she says.

WHILE MOST PRISONERS appear to hail from underprivileged backgrounds, Yerawada Jail also gets individuals from well-to-do families. Bharadwaj writes about the wife of a business tycoon accused of a scam, or those from affluent backgrounds, and how after a while, they adjust their lives to prison time, and she wonders if this might be because they are women. She writes about the creativity of prisoners, of individuals who could rustle up bags from torn clothes, expertly thread another’s eyebrows and draw beautiful rangoli patterns, and how these individuals would be much sought after not just by inmates, but also the constables. She describes how inmates have learnt to use whatever ingredients they can access to improvise and churn out various delicacies, from cakes to bhelpuri and even dahi wada, which is illegal since fermented food is forbidden in jails.

While fights constantly break out, Bharadwaj says, she found jail also a place where there is a lot of friendship and care. “I think that is the only way one can survive in a jail,” she says. “At every stage, I saw, people guiding or helping one another. When someone fell sick, it’s the barrack mates who step in. When a mother beats her child in frustration, it’s the women who break it up and comfort the mother and child.”

When Bharadwaj was first jailed, she soon learnt never to ask another inmate about their case. Most inmates do not like to talk about their cases because they fear, she explains, that the information could be used against them. Bharadwaj was also moved away from the rest of the prison population and forbidden from interactions. So how did she gather her material? “There were plenty of opportunities,” she says. “At the queues outside the Mulakat Room (where inmates meet family members and lawyers), in the police vans on the way to court, or in the court’s lockups.” Or even at common spaces such as the dispensary or the common tap where everyone filled their bottles and buckets.

Although Bharadwaj was in a far more privileged position compared to her fellow inmates, with relatives and friends and lawyers supporting her, she too felt overwhelmed at times. She was anxious in particular about her daughter. She would receive letters from her daughter, and would write to her, often sending pressed leaves from the prison in lieu of greeting cards, but it would take a month or more for the letters to be censored and from them to reach their destination. Sen, her fellow inmate at Phansi Yard, became a particular source of comfort. They would care for each other, share their newspapers and Sudoku puzzles, and during Bharadwaj’s second birthday in Yerawada Jail, Sen even drew her a card. “I don’t know what I would have done without her,” Bharadwaj says today.

Bharadwaj eventually stopped writing these notes, once she was transferred to Byculla Women’s Jail, where she found to her surprise that she was going to be kept among other prisoners and not in an isolated cell. Here, she became many of the inmates’ unofficial lawyer, and it would be unethical, she says, to use the information they gave her to write about them.

Most of the applications she wrote however, were turned down. But there were a few successes, like getting an inmate a copy of her chargesheet or reuniting a prisoner with her child. To these inmates, many of whom rarely even heard from their legal-aid lawyer, just having someone go through their case and file an application meant a lot.

Bharadwaj was also in Byculla Women’s Jail when Rhea Chakraborty was imprisoned there. A television set in the barracks would always be tuned to saas-bahu and reality shows. The remote was controlled by the older undertrials who served the roles of warders and she would have to struggle to get even a few minutes of news shown. But during Chakraborty’s, and later Aryan Khan’s case, the TV was always tuned to the news channels, which were covering these cases ad nauseam. Unlike the way public opinion turned against the two celebrities, inside the jail, Bharadwaj says, the inmates were more sympathetic. When Chakraborty was brought to the prison, Bharadwaj recalls how prisoners would just gawk at her. “But she was a sweet girl,” she says. “When she got bail, she used whatever money she had left in her PPC account [Prisoner’s Personal Cash account, which is used by prisoners to purchase items at the canteen], to give the prisoners a treat.” The inmates had grown so fond of her over time that when Chakraborty was being released, all the inmates came to wish her goodbye. “One inmate even requested if she could dance once for them, and Rhea started dancing,” Bharadwaj says, “and everyone joined in.”

Since her bail, Bharadwaj has continued her efforts to help inmates who reach out to her. She has also begun to work with a senior advocate, and occasionally appears in court. “That’s how I am surviving,” she says. Bharadwaj is also, with the help of a few labour unions, working on labour disputes. Thrice a week, she catches a train to sit at a chamber in Mumbai’s Fort area, where the High Court is located, and sometimes to the office of a labour union in Dadar. She has begun to adjust to her new life in Mumbai (her bail mandates that she remain within the city, and not discuss her case with the media), but she misses Chhattisgarh. “To me that is my home,” she says.

Since her bail, Bharadwaj has also had to relocate homes several times. She’s currently living in a friend’s empty house in a distant western suburb with her daughter. Raising her hands towards the sky, she says, “Otherwise, I would never be able to afford the rents in Mumbai.”

Sometimes as she goes about her day, her phone will suddenly ring, and a familiar voice will ask if Bharadwaj remembers the caller. It will be an undertrial who has just secured bail. “I feel a lightness that I can’t explain,” she writes in the book. “And I know these feelings are going to be with me as long as I live.”