The Politics of Art

IN LATE APRIL 1937, a Basque town was devastated by Nazi aircraft that rained bombs on the civilian population, killing mainly women and children. Barely three months later, Pablo Picasso completed Guernica. Setting aside the question whether all art is political, the canvas, with its suffering humans and animals, is one of the most famous examples of political art in the western tradition (of which there are many other).

In Vinay Lal’s masterly telling, politically engaged art that was contemporaneous with critical events in India’s freedom struggle had a unique trajectory. To begin with, it was marked by puzzling absences. Contemporary artistic representations of defining moments in the Independence movement—for example, the massacres at Jallianwala Bagh in 1919 and Qissa Khwani Bazaar in 1930—are unavailable.

Given this, it is hardly surprising that visual images of the great uprising of 1857, which was the first major challenge to British rule in India, were almost completely colonial representations of what was perceived as an ugly mutiny. The most well-known among them being that of young and pale Margaret Wheeler, pistol in hand, gunning down a dark and moustachioed sepoy during the siege at Kanpur. The sole Indian picture in Lal’s book on this event is a watercolour of Bahadur Shah’s proclamation against the “infidel and treacherous English”. Taken from a 1947 edition of Savarkar’s book (The Indian War of Independence), it pales in comparison with the politically charged colonial images of the capture of the Emperor or the massacre by Nana Saheb’s soldiers of English men and women in Kanpur.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

For the most part nationalist art was seeded in the early 20th century, interestingly with a retrospective twist. Historical figures such as Maharana Pratap, who resisted the Mughals in the 16th century, and Shivaji, who was perceived by some as a symbol of resistance against Muslim domination a century later, would become subjects of a Hindu nationalist iconography. What Lal calls the “Shivaji tradition”, which emerged from a culture of “masculinity, militancy, and the manufacturing of marital pasts” owed in no small measure to Congress leader Bal Gangadhar Tilak. The so-called “father of Indian unrest”, who was instrumental in founding the annual festival to celebrate the Maratha leader’s birth anniversary, was convicted of sedition for publishing in his magazine Kesari, a poem on Shivaji. The book features a number of paintings by artist MV Dhurandhar, which sought to reinforce the saga about Shivaji’s courage and daring; it also contains a watercolour of a composed Tilak, who played a substantial role in the renewed interest in Shivaji, posing beside a copy of Kesari.

However, much of what is contained in the book would not qualify as art, at least in some eyes, being in the form of prints, handbills and advertisements— an assortment that Lal calls “bazar art,” a space he evocatively describes as “sprawling, fecund and unorganized,” often bearing no marks of its provenance. Perhaps predictably, many of the images are of Mahatma Gandhi, and Lal convincingly argues that “the tendency to apotheosize Gandhi and elevate him to the ranks of a deity was present well before his death”. But it is not Gandhi alone who is the subject of the largely person-centric and reverential imagery, an assemblage that includes Bhagat Singh, Subhas Chandra Bose, Vallabhbhai Patel, Jawaharlal Nehru and others. Sometimes, they are featured together in a manner that elevates the quest for freedom over their political differences.

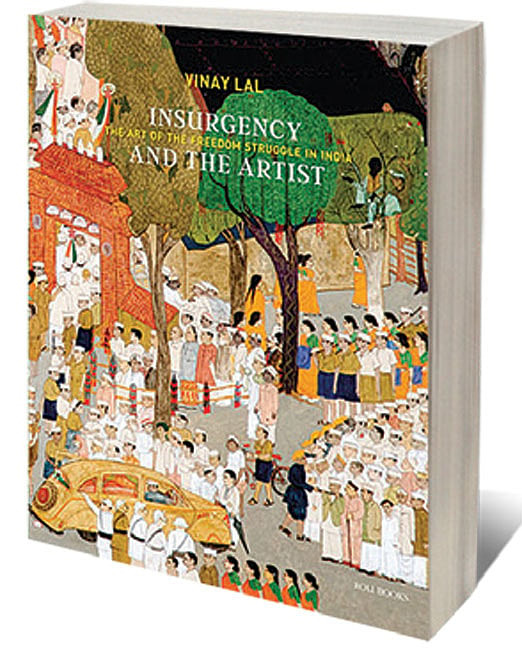

It is after 1942, in a chapter Lal titles, ‘Sunset of the Raj’ that the venerative portraits are fully complemented by those that related directly to political developments—Quit India, the Bengal famine, the bloody Partition and the murder of Gandhi etc. It is perhaps this section, more than the others, that validates the book’s somewhat dramatic title Insurgency and the Artist. But Lal serves up a persuasive narrative right through the book, using the assemblage of images to throw light on the lead characters even as he charts the course that led India to freedom.