The Grip of the Iron Realm

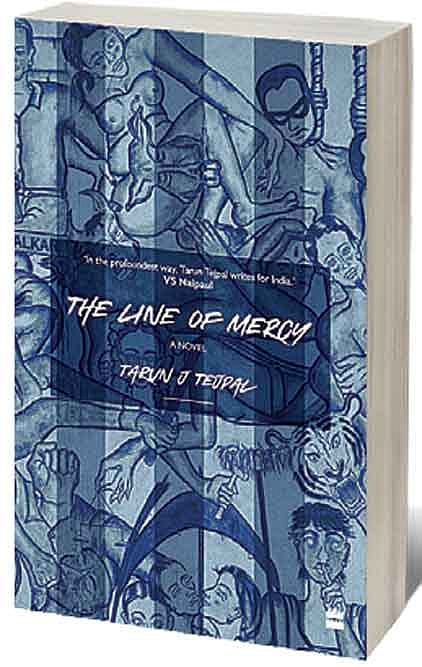

THE LINE OF MERCY is a sea of characters not looking for a story. The strand that connects them is where they are situated—in a prison that author and journalist Tarun Tejpal refers to as the ‘iron realm’, a world of criminals and innocents, all trapped by impulses, proclivities and circumstances, and not all of them seeking redemption either. There is no great hurry to begin or finish anything here. Someone is introduced, the story begins, it veers off as a related character springs up, his story begins and then another and another, sometimes coming back to an original but then again changing direction once more, the layers keep getting added like an onion in the making. But there is no onion at the end.

It is a book of the underbelly, of grime that also lives alongside the passions that make humans capable of leaps and sudden falls. Asambhav, perhaps the only character who has been given any centrality, is an example. It is a love story between a boy and a girl of neighbouring warring families. They run into each other, fall in love and the relationship blooms surreptitiously at the temple through silences and notes. The families conspire against them. She is sent off. He remains, the lost lover wandering in self-destruction and waiting for her return. She eventually does but now married with two children. Until this point it is Bollywood kitsch. It then devolves into noir. He goes to the town where she is staying, lives in her home when the sailor husband is away and the affair rages on. When her husband refuses a divorce, the end is a murder and the iron realm. All of this is spread out in parts across the novel, the narrative that Tejpal employs for all the stories in there.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

The characters are residents of many worlds. If Asambhav is of the ordinary village stock, then Bichoo and his brother Sparkplug are from the slum, their temperaments opposed, one innately vicious and the other without a criminal bone in him. And yet Bichoo’s murders bring both of them to jail because innocence is usually irrelevant in India when the black hole of the system decides to swallow you. There is a portion about the final tipping over of Bichoo into his element that is raw in its violence but strangely plausible because, even though removed from ordinary experience, if all the reins that held a man from reverting to an animal were to come undone, you feel, this could be one way it happens. It begins by him wanting his sisters to fry a fish he had caught after he goes drunk to his house with a friend. When it is refused, he beats them, tries to get the friend to rape one of them and then is filled with regret. They both head to the hut of a fisherwoman who they often have sex with. She tells them to leave because her husband is about to come. He starts to rape her and the husband comes and attacks Bichoo’s friend who is then killed by the woman with a sickle. He kills both of them and then sees their sleeping children and for no reason whatsoever murders them too—“He could never remember if they screamed even once as the noise of the aeroplane passing right above him was so deafening. He kept pounding the rock till the engine’s whine died away. He left the rock where it lay in the wet pulp of the heads and in deference folded back the dry sheet from the feet all the way till it covered the gore. Below the torso their unformed bodies were without a taint. Both of them in loose indigo shorts— their legs frail as river rushes.”

Another group of characters is located in a circus, and the man at the centre of it is Jogen Da, also once called Jogen Jabda, because his first act as an artist was the display of the enormous strength of his jaw. Jogen Jabda’s life is exposited in full, from the time he runs away from home as a boy and finds himself before Shabnam Bandookbaaz, the owner of a circus in a job interview that goes thus; “Jogen could smell her sweat and perfume. The eyebrow gave an order and the man began to strip the boys of their clothes. They did not protest. They stood in thrall with their arms hanging by their sides. She put out her hand and weighed their genitals. She took her hand back and sniffed it and then rubbed it off on her bedcover. The eyebrow ordered the boys be turned around. Her gentle hand went down their spine and over their backsides. The boys could barely breathe. They had never known such sensations. She smelled her hand again and rubbed it off on the bed. The eyebrow spoke once more and the boys were put back into their clothes and ushered out of the tent.”

Jogen finds his calling in the circus. He is selected to train for the jaw act which doesn’t come easy: “After a careful examination of his body parts Mandal Master decided the boy would debut with his jaws. Like a horse, he said tapping Jogen’s incisors and pulling at the molars with thumb and forefinger. This is the only fortune god gave you. A small wooden bit wrapped in cloth was hung by an iron chain and using a stool the boy had to clamp it in his mouth and attempt to dangle by it. In the beginning it seemed impossible. Masterji would hold him at the waist as the stool was pushed away. Then slowly reduce the support of his arms. Jogen would feel the weight of his body begin to shift to his jaws. A panic would spiral as the master withdrew his support. Then the pressure would hit his teeth and his jaw would snap open sending him crashing to the ground.” But he overcomes his fears, becomes good at it, finds other ways to reinvent himself in the circus until he is one of the main stars there. The march of time then comes calling to punish him. He marries, moves away, starts his own small travelling circus, makes a lot of money but then the tent and animals get destroyed in a riot. Aging and increasingly poor, he ends up in another circus to train little girls but there is also sexual exploitation happening there by its owners and when the police bust it, Jogen also finds himself in prison.

Tejpal finds his stride in the extremes but becomes somewhat shaky with the mundane. Everything is sought to be heightened and the issue with so many characters is that while the dark side is fertile because there is so much material possible there, when it comes to the sunnier parts, like love and romance, the telling is often repetitive. In the iron realm is a businessman accused of the deaths of babies, a Hindu bigot-artist who is manipulated into owning the murder of a Muslim man by an aspiring politician who also ends up in the same prison, a migrant labourer wrongly in for a murder and also the real murderer who is in for another crime, and many more like them, all with lengthy backstories. Each could have been separate novellas by themselves given the amount of detail devoted to them. It is one of the idiosyncrasies of this literary enterprise. The tradeoff of such ambition is the patience it demands from readers.