The Free Man

Ah, the joys of reading a diasporic story that's not angsting itself silly over finding one's roots

I'd been complaining recently that it's been a long time since I read just a phat yarn—a well-written story that has both truth and fiction on its side, with half a pinch of glamour. Well, I asked and I received.

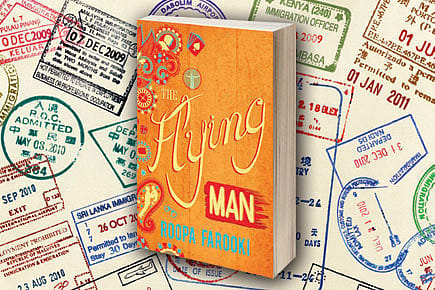

Roopa Farooki's The Flying Man brings us a strong narrative voice with a rich emotional timbre. It tracks the story of Maqil Karam, a good-looking charmer born in Pakistan but resident nowhere and everywhere.

As soon as he clears his school exams, he goes west for a higher education. Most things come easy—languages, politics, card games, women. He is talented and vain, but even his vanity cannot persuade him to do anything that doesn't come easy. Commitment to something, or somebody, doesn't come to him at all. He's constantly evading tax and the traps of familial responsibility. He is, like he tells the mirror, a shallow man. "I don't like causes. I like cocktails and cash and casinos and cars. I like pretty French girls in pretty French clothes."

But France has no hold on him any more than a girl does. He moves countries as easily as he changes names. He marries one woman in Cairo, abandons her, drifts about, then goes back home after his father's death. He sets up a literary club, meets the beautiful Indian expat Samira Rai, marries her, meets with great family disapproval, and moves again. The next few years are a whirlwind of casinos, grifting and love. But, there are children. Children he wants, and doesn't love. Children that Samira doesn't want, and then loves.

To say more would give away too much, but suffice it to say that the adventures and ironic self-awareness of Maqil Karam make the novel a joyful experience.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Besides, for once, it is a relief not having to deal with conventional diasporic angst. There have been far too many novels that simper over samosas—the desire to find, or fight, one's roots. This novel seems to sneeze into the fine cinnamon dust of nostalgia. Its protagonist is the opposite of anything rooted. Karam is a man who not only wants to hack away at his roots, he dismisses the very possibility. He is elegantly selfish, shiftless and rootless.

This offers us a refreshing immigrant experience. I have often wondered why diasporic stories never dwelt with this simple truth that some people want to get the hell out and stay out. After all, compelling economic reasons make people leave their countries, but there's not much that compels them to stay away. This novel is the portrait of a man who doesn't send his children soaking in culture from back 'home', nor tries to rebuild a home abroad. Instead, 'he carries everything he needs in his jacket pocket… His small suitcase is always packed'.

Such a protagonist is hard to like, but Farooki's writing endows him with as much charm as he needs to get by. The narrative itself is reasonably fast-paced, but it doesn't skip on languorous descriptions of people, place or emotion. Farooki is liberal with her similes, which sometimes come clubbed in threes: Maqil thinks of Samira like 'a recovering alcoholic inhaling the dregs of wine left in a stranger's glass at a bar, a sensation as grubby as nostalgia, as delightful as eavesdropping'; and at the casino, the crowd will be stunned by 'his insouciance, his audacity, his disease'. But by and large, the descriptions enhance reading pleasure rather than take away from it.

The novel also offer funny asides, such as the time when Maqil contemplates names: 'There should be a club for people saddled with thoughtless names such as these, for the Richie Richards, Bob Roberts, Gerry Geralds to console one another… His mind starts ticking over with examples of funnier names that he might weave into conversation… Who's that man with the shovel digging her grave? That's Doug Nicely. Who's the gravedigger who forgot his shovel? Douglas Nicely.'

If I have a quibble, it is a minor one. Farooki switches between a first person and a third person voice for no apparent reason. But in general, the narrative pushes towards an inexorable, and sometimes unpalatable, tug-of-war between freedom and responsibility. One can revel in Karam's escapades, mourn his failures, empathise with his wives and kids, and still be left wondering whether or not he got away with it, after all.