Shiva’s Sanctuary

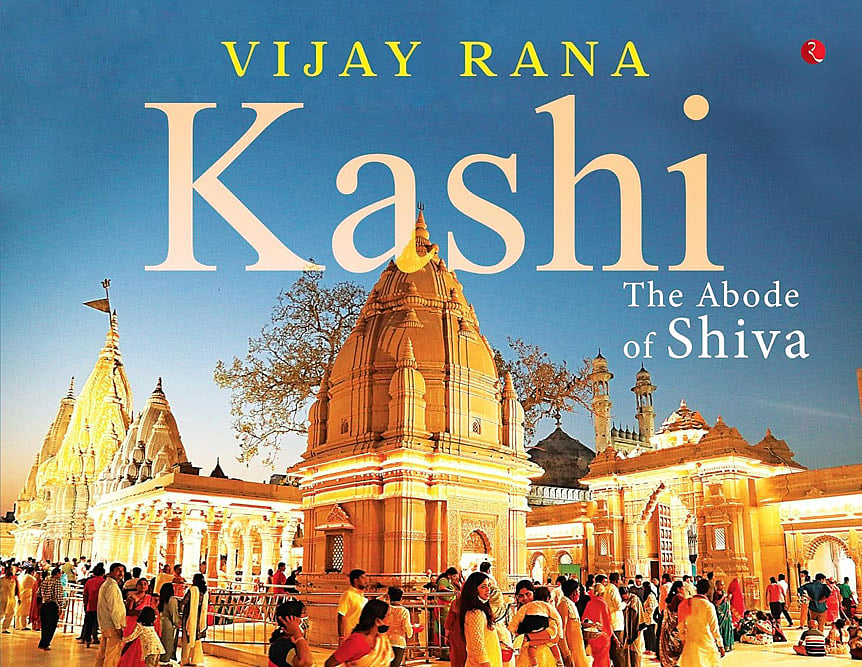

Mark Twain, during his visit to India at the end of the nineteenth century, had famously said, “Banaras is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend, and looks twice as old as all of them put together.” Journalist-photographer Vijay Rana, in his new coffee table book Kashi: The Abode of Shiva, picks up his camera and his pen to take readers through the labyrinthine streets of Banaras, where history, mythology and devotion entwine. Rana’s Banaras embodies the resilient soul of our civilisation — a place where “the greatest of all have come to find what they couldn’t elsewhere” for centuries. Since time immemorial, Kashi has fortified the minds and spirits of all those who have set foot on its soil — from the humblest of devotees to the greatest thinkers from far off lands.

Rana in his new book explores the history, antiquity and sanctity of Kashi, where Lord Shiva himself assured his devotees of salvation if they left their mortal form in the city. In its 144 page journey, the book takes readers from the beginning of time when the holy city of Banaras was created, to Shiva and Parvati making it their abode, to the arrival of the sacred waters of Ganga which helped shape “the spatial characteristics of the city” besides helping form Varanasi’s spiritual and cultural narrative. In vivid details and through both picture and prose, the book captures the luminous ghats and the riot of colours that add to the dynamic character of Kashi.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

At the heart of this ageless city lies the Kashi Vishwanath temple — one of India’s most important Hindu shrines that “despite attempts of destruction, has only risen time and again, each time with greater splendour”.

While the ancient city of Varanasi has been photographed by many over the ages, no visual history of the inner sanctums of the Kashi Vishwanath temple exists because photography is prohibited inside, as is the norm in most Hindu temples across the country. For the very first time, Rana gives the world an exclusive photographic peek inside the temple to preserve the visual memory of the ritualistic practices performed within.

The carefully curated book, divided into two parts, meticulously documents the temple's festivities and stories that connect mythology, history and the contemporary. The photographs capture the devotion of the common people, as well as showcase the presence of Lord Shiva in the popular imagination of the people of Kashi.

The author’s storytelling style is engaging, as he weaves together ancient tales and beliefs and their contemporary significance. For example, Rana highlights how Goddess Annapurna’s bounteous generosity is kept alive even today through the kitchen of a street-side temple, justly called the Khichdi Baba Temple, which serves free meals to the needy. In this way, he skillfully portrays an unbroken link between Kashi’s past and present.

The book also explores in depth Manikarnika, the mahashamshan, “the great cremation ground of Kashi”. Rana describes Manikarnika as the place where funeral pyres have burned ceaselessly for millennia, a place from where souls are finally set free from the “agonizing cycle of life and death”. Digging deep into the ancient scriptures, he traces the history of Manikarnika Ghat, about Lord Vishnu’s penance and the ultimate boon from Shiva that helped Kashi attain its recognition as the greatest of all places for finding salvation.

The chapters of the book are peppered with verses from holy texts such as the Skanda Purana and Annapurna Stotram, given in their original Sanskrit as well as lucidly translated into English. The author in great detail describes the various rituals involved in the three aartis, which when complemented with pictures, brings forth a part of “awe-inspiring” ritualistic practices that have been previously undocumented. It provides a glimpse of the temple’s day-to-day functioning, besides chronicling the frenzy around special events like the Shivaratri and the Rangbhari Ekadashi.

The second part of Rana’s book explores the contemporary significance of the temple. He talks about how the temple had fallen prey to encroachments and disrepair till the arrival of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014 who, while representing the constituency in the Parliament, sanctioned some vital repairs to its structures. Although slow, the work freed up space, gave the temple some much-needed breathing room and in doing so uncovered, surprisingly, 78 other such ancient temples, “many of which had been hidden behind encroached private properties for so long that the residents had entirely forgotten about them.”

In the same vein, the book also follows the journey of the Gyanvapi. History has it that the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb demolished the temple and erected a few domes on the partially destroyed western wall to call it a mosque. The area that is now called the Gyanvapi mosque and the surrounding land had always been one of intense contestation. Piecing together numerous documents and accounts, the book recreates the long-suppressed secrets that lay hidden in Gyanvapi.

With its rare photographs and insightful text, Rana’s book is a unique chronicle on India’s holiest city.