Shehan Karunatilaka: We've lived through war, but the great thing is there’s still hope

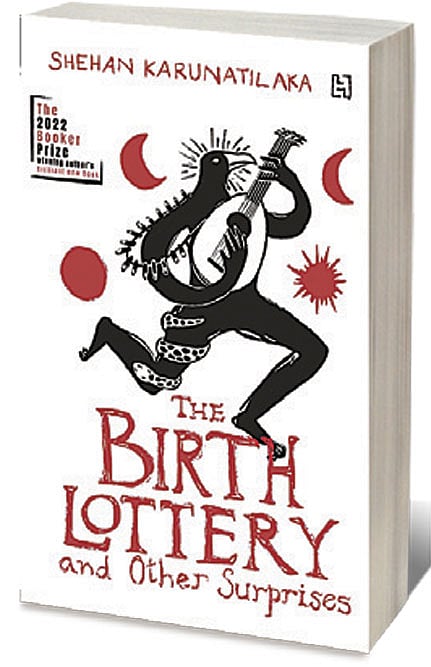

RECENTLY, SHEHAN KARUNATILAKA won the Booker Prize 2022 for his second novel, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida. Packed with talking ghosts and a deceased war photographer trying to solve his own murder over ‘seven moons,’ the metaphysical thriller was awarded for its “hilarious audacity”. Karunatilaka is now out with a truly contemporary collection of short stories, The Birth Lottery and Other Surprises (Hachette; 272 pages; ₹599), which includes conventional short stories—complete with situation, conflict and resolution—and stories that are written entirely like text messages and those that are just a page long.

It has been more than a month since you won the Booker Prize. What have been the worst and best parts of being a celebrity?

I want the book to be famous. I don’t know if I am, though I have been recognised a few times, but that’s why the Covid mask helps. I thought if things get really bad, I can shave my head and my beard and no one will know who I am, but it hasn’t got to that.

The best is suddenly your book is on a platform where the New York Times is reading it. It’s being published in Russian and Portuguese. It’s stuff you dream about, but you don’t really think it being possible, you are content to write the best you can and hope one of the books makes you some money, or not.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

So, the positive thing is this book will be read widely, maybe my first book [Chinaman, 2010] will also get another lease of life and my next book certainly will be read.

The worst is just everyone wants to talk to you! You’re used to sitting in a room by yourself, maybe once a week you go and have a drink and maybe talk to your family also. It is not just interviews, everyone from lawyers to publicists to publishers to agents want to talk to you. So, it’s a bit strange.

I am looking forward to going back to the room where I wrote the books and just spending more time here not talking to people. Damon Galgut, who won last year [for The Promise], said, ‘My friend, you’re not going to write a word in the next 12 months, so don’t expect to. Just enjoy it.’ He gave me some sage advice, but I’m hoping to prove him wrong.

You gave an impassioned acceptance speech at the ceremony. What did you say at the end in Sinhala and Tamil?

Sri Lankan literature is in its silos. You have Sinhala literature, Tamil literature, English, and they don’t mix that much. I didn’t want it to be seen as just a win for Colombo English writers.

I speak Sinhala, I always have. I am not particularly articulate in it, so I just said, ‘I write these books for you, for Sri Lankans. This is a victory even at a time when Sri Lanka has been defeated many times. What a year 2022 has been.’ And also we had just started the T20 World Cup, we lost to Namibia, so I kind of made a crack about that. ‘But it doesn’t matter, we can win the cup.’ Which of course didn’t happen.

I’m taking lessons in Tamil. I asked my Tamil teacher to help me with a few words. So I said, ‘For all Sri Lankans, let’s keep telling our stories, sharing our stories, and let’s keep listening to the stories of others.’

When and how did you decide to get ghosts talking?

Shortly after Chinaman, I was tired of writing about cricket and talking about cricket. I thought Sri Lanka needs a good ghost story. I was looking at what type of ghost story. I thought, ‘OK, what if the victims of our wars, these unsolved murders, what if they could speak?’ And that’s really where it started from. So I leant on that—the idea of using the ghost story to say things about humanity and politics and so on.

Anuk Arudpragasam, another Sri Lankan author, was on the Booker shortlist last year. Hazarding a guess, what do you think you all are doing right?

It’s not just the two of us. There are a number of Sri Lankan writers, mainly in English who have been published internationally, and also have different styles of writing. With Anuk, we are writing about the same country, at roughly the same period, but he’s a much more serious, meditative philosophical writer. Whereas, I tend to crack a few absurdist jokes.

I’ve never met him. I’ve corresponded with him. I don’t know his personal journey, but I’ve benefited from great editing. Sri Lanka has got an abundance of stories. And we have a lot more people writing and hopefully a lot more will after this victory. India has a very vibrant publishing industry and a lot of very, very talented editors. And you see the difference there. I think that really makes the difference and that’s something I’d like to see, aside from translators as well. Again, if we had more of a translating culture, we’d be reading more Sinhala and Tamil books, and they’ll be reading more of this stuff.

In an interview about Seven Moons, you mentioned how when you started writing the book in 2014-2015 you made Maali a gay man and you didn’t think too much about it. You added that if you were to write him today there is a certain question of permission. As a writer, how do you navigate permissibility with the freedom of expression?

I was in Iowa. This was a big topic of contention. And I suppose with good reason as well. It’s usually levelled at white male authors, a white male author writing from a point of view of a disenfranchised minority woman—is that permissible and so on.

But I do agree with the idea that’s what we do. We inhabit different minds. Otherwise, you’re writing an autobiography. I did it with Seven Moons, as it was partially based on Richard de Zoysa an activist, who was murdered in 1989, who was similar, perhaps to Maali Almeida, but certainly not the same guy. He was a closeted gay. It seemed like an interesting subtext, that he really can’t express himself fully in Colombo, he has to go elsewhere to these dangerous places to be who he is.

I’ve been writing some short stories from the point of view of female characters. But I think the lesson here is you do it with respect and you do it with as much skill as you have, and do it with some empathy and responsibility. I think that’s the key thing. So, if I write from a woman’s point of view and I get it completely wrong, or I’m patronising, or I’m just lazy with it, I deserve to get slayed for it and so you need to be aware of that. I was very cautious with this. And I think we should be.

I’ve had criticism that some of my working-class characters aren’t as fully realised as my middle class, and I think that’s something I could plead guilty to. In the end, you’re creating from your heart and your soul, so hopefully you don’t have too many prejudices. So, what you say is authentic.

Birth Lottery has come out pretty soon. What was it like to bring out a short story collection after two big novels?

The short story collection predates both. It was stuff I was doing when I was supposed to be doing more important stuff. When I was supposed to be at my desk working on a pitch for the client meeting, I’ll be working up a short story, or when I’m stuck with Chinaman or Seven Moons, I do some short stories and I’d entered them to these prizes, and they wouldn’t get anything.

Also, this was during the pandemic. Pandemic proved to be quite a productive time for a lot of writers because we were trapped indoors. I collected all these short stories. The short stories have been brewing for many years, and they’re finally complete. I had kids and so that slows down the process. Now my kids are a bit older, so hopefully this door will stay locked and I can get stuff done, but now I have other distractions because as Damon Galgut said, it will be a lit fest for the next 12 months.

At the start of the short story collection, you mention that it shouldn’t be read chronologically and you even have a tasting menu for it, if you want this kind of story, you can read this particular one, etc.

When I was putting it together, I was wondering what makes this a collection, and not much because they’re very different moods. There are some very traditional conventional stories, some almost in a Victorian style of writing, and then some in only text messages and some very short stories. Apart from the fact that they’re all about Sri Lanka, I didn’t really see a connecting thread. This was me kind of figuring out—some stories have twists, some not, in some not much happens, some lots of things happen, some aren’t even stories, more poems.

It’s more of a compilation album. I grew up reading Stephen King’s short story collections and then more recently Neil Gaiman, and those guys love doing their forwards. And I love reading them. I guess it’s making excuses for the fact that it’s not a collection, that it is just a bunch of different elements.

There is a line in the story ‘Assassin’s Parade’, where you write, ‘Criticising your country is not an act of treason. It’s an act of love.’ That seems true to so much of your writing.

There has been an overwhelming avalanche of messages coming my way. Most of them are full of love and congratulations. But there is always going to be backlash, people saying, ‘Why are you talking about 1983 or 89? You are dredging up the past. This is unpatriotic.’

And my claim is, ‘People died in 89. It’s not something I made up in fiction. Sri Lankans killed other Lankans in 83 and 89 and not many of them were punished or prosecuted, and there’s no memorial.’ Is talking about this a treasonous act? This is the debate in Seven Moons as well. There is one side saying, ‘Let go of the past, it’s done.’ And the other is saying, ‘No, dig up the past and address those injustices. Otherwise, there can be no light. You’re just forgetting and repeating the mistakes.’ That’s the Sri Lankan debate that goes on today. We seem to have very short memories.

It’s quite obvious from the books, we tried to forget our past and say bygones, and that hasn’t really worked for Sri Lanka. We tend to go from inventing fresh catastrophes or repeating the old ones. It’s sad that it needs stating, but if you’re criticising your country it’s because you love it and you know it’s capable of much better and greater things and it breaks your heart when it disappoints you, like it has.

And I’m not the only one disappointed with my country. We’ve lived through war, but the great thing is there’s still that hope; ‘OK, now we are not on the streets, there are no petrol queues.’ There’s still that optimism. Which is a lovely thing, I shouldn’t make fun of it.

Criticising is the wrong word, perhaps we should just talk about the things that went wrong quite openly and discuss and debate and argue about it. But at least talk about it rather than pretending it didn’t happen.

As a novelist, what is the lure of gallows’ humour?

It’s part of the Sri Lankan character. It’s part of my sensibility as well, it’s just an absurd country. You have to point these out and maybe even chuckle at them. Even our recent protest. What were the images? The populous rising up against the heavily armed military power doesn’t usually end happily. We were very, very worried and scared when this was happening. But what were the images we saw? A bunch of people jumping in the president’s pool, sitting on his couch watching the cricket, re-enacting IMF meetings. It was a hilarious variety show. A lot of Sri Lankans appreciated it, even though you know the state later went after some of these characters. There was a sinister edge to it, and now that moment has been tinged, with various agendas and narratives. But that moment we remember; it was a scary moment, it changed history. The president fled. A feared president fled, but also there was that absurdity to it, which is very Sri Lankan. And so when describing these situations, I tend to gravitate towards that, because it seems unique, and it makes these grim topics more palatable to a reader who knows nothing about Sri Lanka. I guess I get more philosophical in Seven Moons, the idea that existence is also a cosmic joke, and I think it goes into that territory as well. Absurdity—there’s an abundance for me to write, especially if I keep living in Sri Lanka.

I read somewhere about how you write from 4AM to 7AM. Is that your daily writing schedule?

Yeah, I’ve been slacking off in the last few weeks. That’s the time when I’m deep into a project, that’s the only schedule that will work, because you can’t miss a day, you have got to write every day. Advertising, especially when you get more senior, it consumes your entire life and so four to seven was the time that the phones were not ringing. There’s no one bothering you, and those are three solid hours. And when I had kids the same thing applied. After 7-8AM the kids wake up. Of course, it means you got to sleep properly. Now I try to make sure I go to sleep around the same time as the kids, so I get a good 7-8 hours. It sounds hard. But you do that for a week, two weeks and you’ll have a project. You do that for a year, you will have a novel that may or may not be good.

The Birth Lottery, ends with an ‘unpublished interview’. Inspired by that, I ask you, what is a question that you wish you had been asked that you haven’t been asked?

That’s a tough one!

No one has asked me about hair and beards, I have a lot of answers. George Saunders has got a great beard. The correlation between great literature and facial hair and all that. I have a big theory. Middle-aged hairy male writers don’t get asked about their looks as much as Jhumpa Lahiri does, so let’s redress that balance.