Sense and Sensuality

‘NOTHING SELLS LIKE sex and violence’ is a dictum every author has been told at one point of time or another. The statement always triggers a question which is rather simple and straightforward: Why? Why do sex and violence sell so well? Why are these elements so relatable that they almost have a universal appeal? The question swirled in my mind till the answer came to me from quite an unexpected source.

Reading The Anatomy of Violence: The Biological Roots of Crime by Adrian Raine, I understood that violence can be classified as one of our prime instincts which needs to be conditioned and controlled. It’s an ‘evolutionary throwback’ to more primitive primates. But why did the primitive species need violent behaviour to be so intrinsically infused in their genetic setup? Simple—for survival. If they didn’t fight back, they would die. Why violence had such an easy appeal to humans when it came in the form of entertainment was explained to me by this discovery, but what about sex? The answer was contained in this very idea—survival. Humans have to reproduce in order to keep their species alive and hence it is a part of their genetic setup. That draw, that tug of attraction and those passionate desires are in our blood. We have this inclination, this interest and this active desire so that our species lives on. Everyone has this in their DNA! Everyone has the appetite for it and hence erotica sells so well.

Zooming in on the idea of eroticism in literature and its appeal—why has eroticism been a part of (Indian) literature since its earliest recorded forms? Many state that nothing in this world can have a universal appeal, not even god. But erotica seems to come very close to invoking universal interest. The reason is quite obvious but to explain clearly, I will take the support of Gurcharan Das’ statement in his book, Kama: The Riddle of Desire, where he explains that sensual excitement is passed on from our senses to our imagination creating a pleasing fantasy, which can create a physical arousal. In my opinion, this pleasurable experience is what draws people to erotic fiction. It has an appeal, and hence it has demand.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

Writers and thinkers from the Indian subcontinent understood the relevance and importance of eroticism very early. The Rig Veda, believed to have been composed between 1700-1100 BC, contains a conversation between Lord Indra and his wife Indrani in Book 10, Hymn 86. Some English translations read in more detail than others but none deny the presence of erotic tones between the husband and wife in this hymn. In the conversation, Indrani authoritatively states that there is no other wife more pleasant and righteous than her, no other woman who can receive sexual embraces better than her, no one can shake her figure better than her during their moments of physical intimacy, no one can raise her thighs better than her. Her speech establishes her equality in their relationship.

Other examples that testify to the presence of erotic themes in Indian literature are the stories of Shiv and Shakti (which have clear erotic tones), Kamasutra, of course, and many works of Kalidasa. Meghadutam and Abhijnanasakuntalam have enjoyed massive recognition and become a part of popular culture but when it comes to eroticism in Indian literature, another work by Kalidasa called Kumarasambhavam demands mention. The epic poem describes the courting of the ascetic Shiva by Parvati, the conflagration of Kama (god of desire), the wedding and lovemaking of Shiva and Parvati and the birth of their son. It’s an interesting read if you have an appetite for such writing. Wendy Doniger in The Mare’s Trap states that a canto in which the union of Shiva and Parvati is described is so erotic in nature that some scholars refuse to accept it as part of the poem.

Apart from their acceptance and appeal, why were such themes a part of such important texts? Striving to achieve commercial success does not seem a befitting answer here. My guess is this was done to cultivate a healthy society—to bring about gender equality in society; to promote the idea of gender equality as opposed to subjugation. In these texts women are not marginal. The Hymn from the Rig Veda clearly states the importance, status, need and position of Indrani. But what happened then? Why did we start looking down upon eroticism that writers, thinkers and common people had once celebrated so openly? Are the multiple invasions into the region over thousands of years to blame? I am not sure. Then what is the reason? Have we regressed? Maybe people were more civilised in the past? Maybe the toxic masculinity and overpowering patriarchal mindset was less prevalent back then?

If I were to recollect my early impressions of eroticism in Indian literature, the first set of imagery that comes to my mind are from the Amar Chitra Katha comics I read as a child. Even today, I distinctly remember some of the voluptuous images I had seen in the issues titled Urvashi and Shakuntala. What comes to my mind next is the epic fantasy Chandrakanta. In my late teens, I was able to procure a hardcover edition of the book in Hindi. I remember being shocked, at first, by the kind of language used in the book, but soon learnt to enjoy the story with its romantic and soft erotic tones.

Today, if I were to pick up an author from my own library whose eroticism I have enjoyed immensely, it would be RK Narayan. The soft eroticism that he uses comes in a limited dose, leaving an indelible impression on one’s mind. The way he describes Rosie when Raju lays eyes on her for the first time in his landmark novel The Guide is just delicious: ‘... eyes that sparkled... a complexion not white but dusky that made her half visible—as if you saw her through a film of tender coconut juice.’ Her lithe, supple figure is described in a way that reminds one of the smooth, gliding movements of a snake in the novel.

Another book that I enjoyed reading was the 2013 collection of erotic stories, A Pleasant Kind of Heavy. The vivid imagery used in the book is crafted so well that it stayed with me for long. With a glamorous contemporary setup, Ananth’s Play With Me also deserves special mention.

In recent years, an interesting phenomenon has set upon us. Fifty Shades of Grey was a blockbuster book and the translated Swedish book series Girl with the Dragon Tattoo gained global recognition. These are only two of the many examples where erotic, sexual themes have been intertwined with violence. The Indian reader has also developed an appetite for stories with similar themes in familiar setups. The recent success of the Stranger trilogy and Black Suits You by Novoneel Chakraborty have triggered many questions and mixed reviews. The predatory nature of the characters and what some identified as a ‘lame justification’ of female rape and criminal behaviour raised eyebrows. The psychological impact and influence of such stories has always been a subject for heated debates but no one can deny the fact that such books have started a conversation.

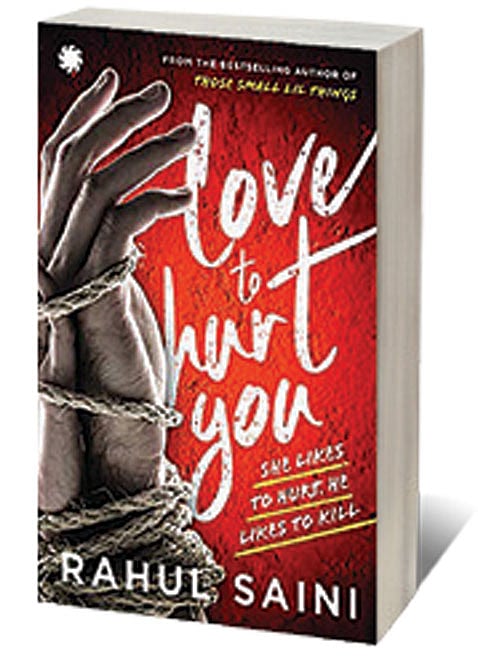

In my novel, Love to Hurt You, I have tried an experiment. Not only have I intertwined erotic and violent themes, I have also developed a female character more powerful and dominating than the men around her. She inflicts the kind of treatment on men that women are generally subjected to in stories we have read recently. I have created an inversion, a role reversal. A female character with masculine aggression? Maybe, or maybe not. Because aggression is just aggression, right? Neither feminine nor masculine.