Salad Days of a Natural Leader

The beginning of the Assam agitation coincided with Himanta transitioning from Gandhi Basti’s government primary school to Guwahati’s prestigious Kamrup Academy. With new beginnings, many new horizons stood to be conquered. It was almost as if the pieces of a puzzle were falling in place.

It all began in Patacharkuchi, a little town in the west of Guwahati. This is where Himanta spent a few days every year during his break after the exams. Himanta’s grand uncle was the local doctor there. According to Himanta’s uncle Gagan Sarma, the little boy loved Patacharkuchi and often forced his mother to let him stay there for much longer than what had been intended.

The year was 1979 and the Assam agitation was still not the talk of the town when Himanta arrived in Patacharkuchi. Although he was only in class five, Himanta’s household had been such that there had never been any escape from the issues of the day. Not that Himanta sought an escape, quite the contrary. In Patacharkuchi, Himanta found the intensity to be at much higher decibel levels. This was because his uncle, the doctor’s son, was an office bearer of the Bajali College student body. With AASU’s mobilization efforts in full swing, the Assam agitation was taking campuses across the state by storm. One of AASU’s programmes was to conduct large rallies across the state, so a rally was planned in Patacharkuchi. Himanta’s uncle was one of the main organizers.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Himanta was swept in the excitement. He began assisting his uncle and helping out with the arrangements. As is often the case in such situations, the sincere little boy caught everyone’s attention. But helping out with a big event was only half the story. Himanta was inquisitive and seemed to take a keen interest in the immigrant issue. For the organizers, it was evident that the little boy was not just trying to be part of something, but was quite taken up by the cause.

A huge crowd gathered at the Patacharkuchi Vidyapith on the day of the rally. Senior student leaders whose stars were on the rise were present for the occasion. Himanta remembers senior leaders such as Jeherul Islam and Nekibur Jaman on the dais. Once again, the little boy who was helping out caught everyone’s eye. It was suggested by one of the organizers that he too rise on the dais and speak to the crowd, and the idea quickly gained traction among the inner circle. Himanta didn’t have to be nudged twice. He eagerly took the stage as thousands watched in amazement. Himanta was no stranger to the stage. He spoke fluently, as if he had done it for years. He underlined passionately how illegal migration from Bangladesh had caused huge social and economic problems in Assam. At first the crowd was stunned, for it wasn’t every day that they heard a ten year old delivering political sermons. Then, the crowd went into a mad frenzy, cheering and clapping loudly. Himanta had stolen the show, a phrase one keeps hearing in the context of Assamese politics even today. This was the beginning of Himanta’s public life, and thereafter, there was no looking back.

Upon his return to Guwahati, Himanta wasted no time. He plunged himself wholeheartedly in the Assam agitation. One of Himanta’s unique traits first came to light during this period. Whenever Himanta becomes part of an organization, he rises the ranks quickly by becoming an indispensable cog. Never shying away from work and responsibility, those at the helm become dependent on him. Whether the others like it or not matters little, for he gets things done. Very soon, even in the case of the Assam agitation, the little boy who was yet to enter his teens was handling key responsibilities.

Himanta’s classmate from Kamrup Academy, Rajib Hari Kaushik, remembers the period vividly. “He was always simply dressed, in shorts and hawai chappals,” Rajib recalls. “A dairy farmer called Pannalal was one of his neighbors, and he often hitched a ride to school in Pannalal’s horse cart. Sometimes he came to school standing at the back of a rikshaw, with his feet placed above the two back wheels. It was a free ride,” Rajib laughs.

This joie-de-vivre and happy-go-lucky attitude are traits that were intrinsic to Himanta even as a child. However, as the months progressed, Himanta’s classmates at Kamrup Academy saw much less of him. “He came early in the morning, left his school bag there and pushed off to the AASU office,” Rajib remembers. “By the time we were in class nine or ten, we barely saw him.”

Even in high school, Himanta’s political instincts were sharp. He was always seen when it mattered, whether it was student body elections, demonstrations or debates. Perhaps under normal circumstances, this selective regularity might not have been entertained. But those were the years of the Assam agitation. And as the agitation progressed and gradually took the entire state by storm, Himanta’s absences increased and the school authorities increasingly looked the other way.

There were other reasons for Himanta not earning any ire in school. With the Assam agitation becoming the main talking point in the state, many of the debating competitions were centered around the issue. Due to his proximity to the cause, the arguments came naturally to him. Moreover, his elder brothers were well-established debaters on the Guwahati debating circuit, making him a natural choice to represent his school in such competitions. Himanta worked hard for these competitions, often taking time out after classes to sit with teachers and go through his arguments. In a newspaper article many years later, he recalled how his father, who always encouraged discussion and debate at home, often helped him frame his arguments. Himanta won many laurels for his school in these competitions.

Having made a name as a strong debater, and being closely associated with the Assam agitation, Himanta was a natural choice to be on the student body in high school. He was elected to the body as the assistant general secretary for the first time in 1982. This was the first election Himanta ever won, and his tenure allowed him to test political waters for the very first time. On the occasion of the school’s silver jubilee, Himanta got the statue of a martyr installed on the campus, using the surpluses from the pooja collections. This was widely appreciated by the school authorities. However, their appreciation was short lived. A booklet was prepared for the occasion, which would be presented to the students. Upon going through the boolet, Himanta was furious. He gathered the other students and delivered a hard-hitting speech about the booklet having no mention of any issues that affected the student community. He called upon his peers to boycott it. As the silver jubilee celebrations came to an end, a giant pile of booklets stared back at the authorities in the teachers’ common room. Perhaps it was at this point that Himanta realized he could be both constructive, as well as a firebrand street-fighter. Himanta would go on to become the student body’s general secretary in his final year of high school.

Meanwhile, as the Assam agitation gained steam, Himanta was on the ascendent. Back then, AASU functioned out of the Guwahati University, where the organization’s top brass lived. Himanta used to arrive there in the morning after his guest appearance in school. Upon deliberations with the leadership, he would be tasked with various works. On some days, he would be given copies of AASU’s press statement and instructed to deliver them to the media. Himanta would place the stack of papers under his bicycle’s carrier, and ride from one newspaper’s office to the other distributing them. On other days, he would be asked to paste posters or paint slogans on walls. These activities were diligently carried out. Himanta perhaps realized back then that among the shortcuts to climb the ranks was to take up non-glamorous but essential tasks that most people avoided.

Soon, Himanta was given more important responsibilities. The agitation’s main rallies used to take place in a ground known as Judge’s Field. As the agitation progressed, the ground would become somewhat of a fortress. But back then, Himanta was tasked with organizing some of the rallies and mobilizing students to show up. Before the senior leadership took the stage, Himanta often addressed the crowd and kept it engaged. Sometimes, he served as a filler in between their speeches. The crowd loved Himanta, who was not just the youngest speaker but the shortest one as well. They often prompted him to stand on a table when he spoke, so that he could be seen clearly. Himanta became such a crucial part of AASU rallies, from organizing them to keeping the audience engaged, that the young AASU leadership began taking him along when they toured the state.

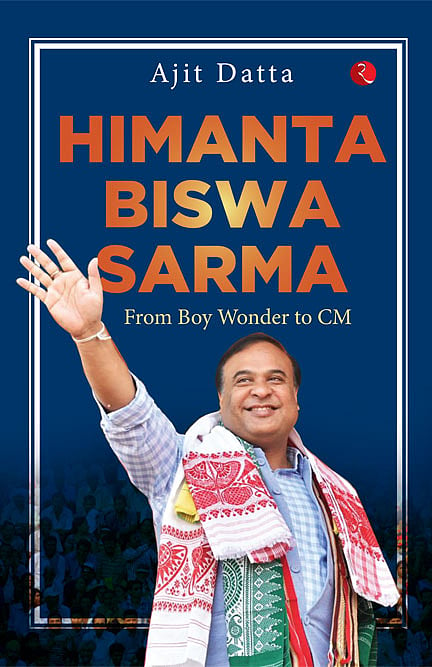

(This is an excerpt from Himanta Biswa Sarma: From Boy Wonder to CM by Ajit Datta)