Roots of the Raga

Priya Purushothaman’s The Call of Music lands at my desk barely an hour after I’m back from my counselling session with my therapist. Having lost my mother two months earlier and having experienced the end of another significant personal relationship, I have stopped singing. “I feel like grief sits in my throat, refusing to let my voice out,” I tell my counsellor.

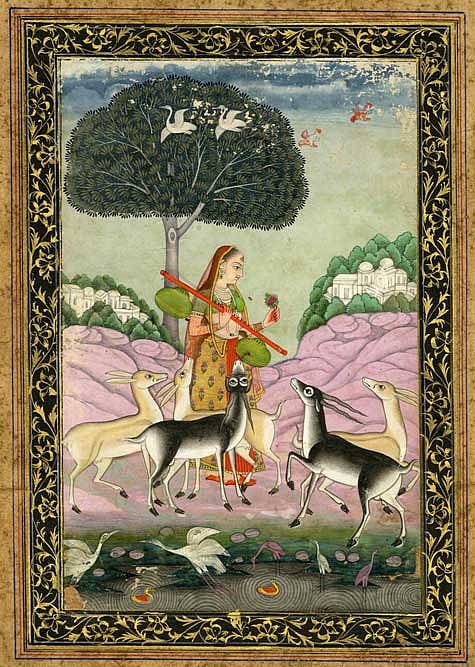

Music is complex. For those of us who live with it and don’t treat it as a hobby (abhor that word), it’s our constant companion, our shadow, a living entity that can heal us but also makes us feel outraged at times. A raag’s complexities or a thumri’s innumerable expressions become a maze to enter. You need to navigate the melodic chakravyuh carefully, going deeper into crevices and areas that you haven’t seen before but eventually finding yourself on a clear path.

Purushothaman’s remarkable book, in a way, rescues me from the depths of darkness that I’ve been experiencing lately as someone who’s stopped doing riyaaz or practice that a student must do daily.

Purushothaman’s in-depth conversations with eight musicians of “Hindustani music” are an exploration into bringing forth a voice that’s ultimately fresh, unadulterated, and significant. It helps that the author has included a curated playlist at the end of the book, featuring the music of the artists she has interviewed. The author is gentle in her approach while interviewing these artists, asking relevant questions (she’s a reputed Hindustani vocalist herself), drawing on her own experiences of knowing some of them, as well as her longing to find answers, just as any music practitioner would.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Rumi Harish’s voice in the chapter titled ‘Singing Gender’, for instance, is both bold and endearing, the artist talks candidly about feeling “orgasmic” and “wet several times while hearing the male tanpura”. Linking theatre, classical music, and activism, Harish’s artistic oeuvre provides insight into singing beyond gender. The two-part chapter on Sudhindra Bhaumik, also the guru of the author, is delightful because it allows readers to pause, think, meditate, and reflect on how some musicians, in the world of chaos and noise, still manage to live with simplicity.

This is a book that should be in the hands of everyone—whether you sing, love or understand Hindustani classical music is immaterial. Every page feels like lessons in discipline and consistency, in understanding life from a fresh perspective. With detailed interviews with Alam Khan, Kala Ramnath, Shubhada Paradkar, Suhail Yusuf Khan, Shubha Joshi, Yogesh Samsi, peppered with her observations, the author writes with sensitivity to ultimately give us a much-needed book that offers not only music-related gems but also lessons in parenting; discipline; consistency; the spirit of acceptance and surrender while being on the “crazed thirst for knowledge”. Be it Joshi’s angst in her initial years of not having the quintessential high vocal range, or Suhail Khan’s quest as an academician in knowing the sarangi or Harish’s “love-hate relationship” at one point with music, every chapter is an attempt to distil the essence of music that’s deeply personal, allowing for deeper introspection through the magic of raag, taal and laya.