Return of the Sage

This stark telling of the swift ascent of a political demagogue is a compelling commentary on modern India, despite a simplistic take on the ancient master of statecraft

Any tale narrated by Chanakya—the teacher and philosopher widely identified as 'Kautilya' or 'Vishnugupta' who authored the Arthashastra— would be intriguing. More so when the narrator is a spirit that is reborn to this world after thousands of years in the void. Rebirth is the reason for Chanakya's presence in Murari's world, but as for the how of such a thing, Chanakya replies, 'I cannot answer… despite my years of non-existence, as I did not find [God]… I am embarrassed by this to a certain degree. Especially as I was a Brahman once, a believer in Mahavir and am now an unbeliever'. There is a beauty to simplicity, but it is entirely possible to wield Occam's razor too bluntly.

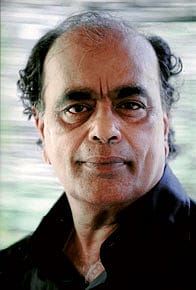

Timeri N Murari is known for his bestsellers The Taliban Cricket Club (2012) and The Taj (2007). In his latest novel, he is no less engaging, speaking to jaded modern India with acerbic wit. His Chanakya—once Mohanlal, the son of a modern day farmer who finds himself possessed by the spirit of the ancient strategist—is a dry, humourless man who believes in neither God nor love, driven only by desires honed by 'sucking on star dust for more than two thousand years'. Burned at a young age in an accident, Mohanlal finds that 'something mysterious was growing in my mind… Mohanlal was receding; Chanakya was growing more powerful, claiming my thoughts and my heart'. The grown up Mohanlal, now calling himself Chanakya, is a somewhat unsummoned guide who inexplicably is given charge of Avanti, the daughter of the President of a nameless state in India. Avanti is conflicted between her love for her father, her ambition and the passion she feels for a filmmaker she wants to marry. The novel begins with the latter conflict: in Chanakya's own words, 'His name is Aditya, a nobody, and love will only lead her to the role of a housewife, serving one man and not a nation'. But Murari explores a more risqué angle as well; there are suggestions of a less than platonic relationship between Avanti and her father.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Politically, the dynamics of this tale is fascinating. Murari presents Chanakya as a man who renounces all idealism in favour of naked ambition. As his protégé, Avanti swiftly follows suit, rising through the party ranks as she sheds her scruples one by one.

On the eve of Avanti's first election campaign, for instance, there is not even a suggestion in their council of war that the election be fought on real issues, or with the aim of actually bettering the lot of 'the people'. Instead, Chanakya blandly states, 'We make a list of promises for the poor, trailing them as a fisherman the hook in the flowing waters'. This may be a true reflection of today's politics, but it is rather odd to hear Chanakya—a historical contemporary of the Buddha, born in a time of deep philosophy and sound morality— speak as though his understanding of dharma and karma were at the same level as those of today's leaders. The character speaks as one schooled in the Arthashastra, rather than as the one who wrote it; and while his infatuation with actress 'Siggy Chopra' may have been intended to humanise, it trivialises instead.

The novel's strength lies in its caricature of reality: Avanti's best friend Monika, the daughter of the wealthiest man in the state, 'lives in a thirty-floor building… [that] towers over the city and peers down at the slums at its feet'; while the mercenary habits of today's godmen mean that— 'Even on the pathway to heaven you have to pay the toll before you start the journey'.

In terms of style, the book is both brisk and eventful. However, in a curious choice of grammatical flourish, the text does away with quotation marks entirely; forcing the reader to either slow down and pick apart sentences individually, or speed up and sacrifice complete understanding in the pursuit of narrative flavour.

Chanakya Returns is worth the jacket price, but if it has a weakness, it is this: were it not for the fact that the narrator grandly declares himself to be the Chanakya, one could quite plausibly have imagined him as Lalu instead.

(Aditya Wig is the author of the forthcoming fantasy novel King's Fall, an alternative history of Chandragupta Maurya)