Reading in the Time of eReaders

You can change text size, you can carry a library in your bag. Yet, what it really takes to get hooked is not the gadget, it's a good book

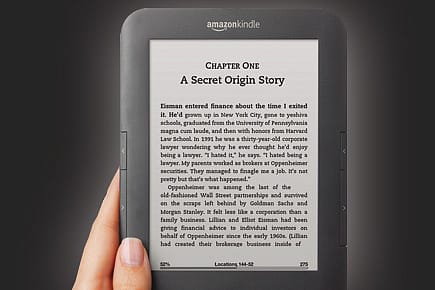

To carry all the Harry Potter volumes, along with Dostoevsky's short stories and a few other titles in your handbag, can be empowering. Especially if it weighs and occupies the space of a DVD. You can read on the pot, in bed, you can read with one hand towering over all those frizzy haired people on the crowded local train without hurting your wrist (or someone's head if you drop it). But you can't read in the darkness of a late night ride home, because Kindle, Amazon's e-book reader, has no backlit screen.

A month after buying an e-book reader, I actually regretted the decision. My logic behind buying it was simple: I don't want to be roadkill on the tech highway. An e-book reader looks like the logical next step for readers, especially ones who live in places like Mumbai where some tenants occupy as much space as the Encyclopaedia Britannica. But when the grey-coloured tablet actually arrived, I suddenly realised that I had a bunch of books piled up by my bed, waiting to be devoured. I was buying time by reading those ignored, musty, dusty books—because, the truth is, new technology makes me procrastinate.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

You have to learn something new. You have to set it up, negotiate a new interface that doesn't look half as exciting as other screens because it's functional. It's black and white. It's nothing like what you had imagined. Every person who has held my Kindle touches the screen with eager fingers, mistaking it for a touch screen. The Kindle is the poor cousin of the iPad, which everyone aspires to have, some secretly, most openly. Although one is an e-book reader and the other a tablet computer, when it comes to technology, I have realised there is no logic. Only lust. People curious enough to fiddle with my Kindle generally compare it to the iPad, assuming one buys it because one can't afford the other. But if reading is your sole obsession, then the Kindle beats the iPad, because reading is its sole purpose. It's lighter, smaller, has buttons on both sides to turn pages, and has a battery life that will last for months, unlike the iPad, which will blink off in a day or two. You can put your glasses on the Kindle and fall asleep without worrying about potential scratches to the screen.

Initially, I found it disconcerting to read without page numbers. The e-book reader can tell you how much you have read in percentage terms, and the line numbers you're on. But sometimes, you just want to flip through pages and feel the weight of what you're consuming. Also, since this is technology, margins have been discarded to maximise space. Margins have historically been the empty space that the reader and writer share. Space for doodling, scribbling and making other markings that reveal your individuality and vandalism. Reading without margins is like watching a Hindi film without an interval. It's not a real change, yet it is a big deal.

But all these are transitional problems that can be sidestepped in the face of a bigger gain. By which I mean books that don't make it to your friendly neighbourhood bookshop that stocks more children's games and music than actual books. My frustration with bookshops began last year, when I spent three weeks looking for Kalidasa's Meghadootam in English at all major bookstores in Mumbai, even placing orders with some. Luckily, my father found the book for me at Prithvi theatre's small bookshop, and saved me the tragedy of buying Kalidasa on Amazon.

When Jose Saramago passed away last year, I read his obituary online and was inspired to read one of his books, The Gospel According to Jesus Christ. Since I couldn't find it at either Crossword or Landmark, I reluctantly purchased it on my kindle for Rs 700. The book, it turns out, transformed me into a Kindle reader overnight. It made me learn how to highlight, change text sizes and engage with this new technology. The truth is, all you need is a good book to have you hooked. Whether it's on Kindle or paper, it ceases to matter eventually.

Free books online are touted as incentives for buying an e-book, though not all free books are legally available. The Harry Potter series I downloaded are a pirated version. Author JK Rowling was apparently against selling them as e-books because she was afraid they'd promote piracy. A review of the Kindle by Nate Anderson on arstechnica.com touted how the coolest feature on Kindle wasn't one created by Amazon. It is Project Gutenberg, which has made tens of thousands of books legally available free online. I recently downloaded the 'Magic Catalogue', a list of books I can download free from the site. But as one of my friends browsing through my Kindle put it, "Who reads these books anyway?"

Most books available free online tend to be either obscure or classics. Perhaps the only way people will read Tristam Shandy (Laurence Sterne) or Lucky Jim (Kingsley Amis) is if they are free. Perhaps, even that won't work. In my long list of noble intentions, I downloaded Moby Dick onto my Kindle free, but I didn't go beyond 'Call me Ishmael', the opening line.

Nostalgia is the cliché that welcomes most new ideas and technologies. In one of the hundred product reviews of Kindle the world over, I am certain at least one would have predicted the death of the regular book. Lamenting the loss of the orgasmic smell and pleasures of a yellowed, leather-bound book, complete with an epitaph.

But just as all the microwave ovens, rice cookers and roti makers of the world couldn't displace the humble gas stove, nothing can displace the actual book. People will still hound famous authors with books to inscribe, and toddlers the world over will continue to defile any book they come across with pens and crayons.

More importantly, the book as we know it died long ago, even before the invention of the Kindle. It died with the invention of page-turner bestsellers, books that reviews described as 'unputdownable.' Readers got so caught up in turning pages and racing to the end that they lost their ability to pause and reflect on the page itself. Besides, when was the last time you bought a book you wouldn't like to part with once you read it? To put it differently, when is the last time you bought a book that you'd like to re-read?

Milorad Pavic, in his lexicon Dictionary of the Khazars laments the loss of the reader. 'The reader capable of deciphering the hidden meaning of a book from the order of its entries has long since vanished from the face of the earth, for today's reading audience believes that the matter of imagination lies exclusively within the realm of the writer and does not concern them in the least… this type of reader does not even need a sandglass in the book to remind him when to change his manner of reading: he never changes his manner of reading in any case.'

E-book readers are designed for precisely such readers—who don't change their manner of reading, who expect books to fit their taste, instead of expanding their tastes to accommodate new kinds of books.