Nirmal Verma: A Moral Life

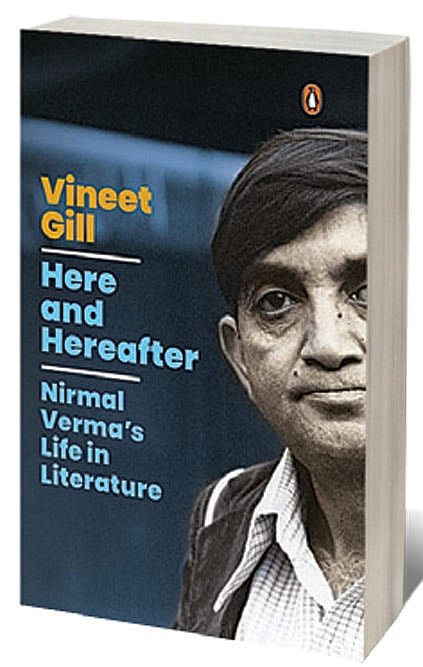

THE INTRODUCTION TO Vineet Gill’s Here and Hereafter: Nirmal Verma’s Life in Literature ends with the declaration: “this is not a biography”. Earlier, Gill distances his book from the techniques and methodologies of the contemporary ‘literary biography’ (“the nitty-gritty of how many words a writer does in a day, how many drafts”) which he also dismisses as “meaningless, like most genre terms”. He also insists that the facts of Nirmal Verma’s personal life aren’t particularly interesting to him. By the time you’re at page 15 or so, you realise this is a necessity because of the atypical nature of Gill’s enterprise — tracing the development of the “writerly sensibility” that Verma (and, as Gill points out, serious writers around the world) displayed in his Hindi novels, short stories and critical essays.

If the bildungsroman’s focus is the protagonist’s moral and spiritual coming-of-age, what Gill has attempted in Here and Hereafter is closer to the Künstlerroman, a narrative that dissects the making of an artist, the array of influences, thought-systems and experiences that contributed towards the elusive “writerly sensibility” in question (think Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home or Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels). This would be an ambitious venture in the context of most literary titans but even so, Verma represents a special case—here was a 20th-century Hindi novelist more ‘international’ than his English counterparts (look at Kavve Aur Kaala Paani or Antim Aranya) but seldom counted among the exemplars of ‘world literature’. Here was an intensely cosmopolitan thinker who was also, for complex reasons, hopelessly beholden to certain Hindu religious and aesthetic traditions.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

And Gill does an excellent job of breaking down his disparate influences in a calm, unhurried fashion; the picture of Virginia Woolf in the young Verma’s room, the issues of Kesari (a magazine published by the Gita Press) read by his grandfather, his ‘frenemy’ relationships with fellow Hindi writers like Krishna Baldev Vaid—and, of course, Verma’s conception of ‘European’ as a shared idea, a feat of the imagination rather than a meaningful political, racial or religious category. Gill is not only a supremely attentive reader of Verma’s novels (and Hindi literature as a whole; his meditations on Agyeya and Rahul Sankrityayan are equally impressive), he’s also deeply invested in the idea of Hindi literature being a precursor to the kind of novels contemporary commentators love to club under the ‘world literature’ umbrella.

“Bharatendu Harishchandra, one of the pioneers of Hindi writing, translated, among other texts, Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice into Hindi. Premchand brought all sorts of influences—from Tagore to Ruskin—into his writing. The Chhayavad poets were indebted, in both direct and subliminal ways, to the British Romantics. This is to say that the ethos of give-and-take—crucial to all paradigms of modern thought—is the sine qua non of the Hindi tradition. Yet, most would hesitate to call it world literature.”

And on the odd occasion where Gill does slip into a more conventional biographer’s mode, there’s usually a compelling reason. Like this priceless passage about a childhood game played by Verma, something that in retrospect feels both macabre and very much in character.

“As a child, Verma would play a game, a sort of death simulation. He would hold his breath for as long as he could and try to fit within those moments as many recollections of his life as possible. An attempt at a pre-mortem flashback, as it were; a child’s pretend version of a near-death experience. But also, an uncanny rehearsal of an idea that would become important to Verma as a writer and thinker: that remembrance is the only viable response to death; that memory can work as an antidote to mortality.”

Over the last decade or so, there have been a handful of books that have portrayed writerly development in wholly original ways: Colm Toibin’s New Ways to Kill Your Mother: Writers and Their Families (2012) and George Saunders’ A Swim in the Pond in the Rain (2021), for example. To my mind, Here and Hereafter belongs to that rarefied group, because of its ambition and its close-reading excellence.