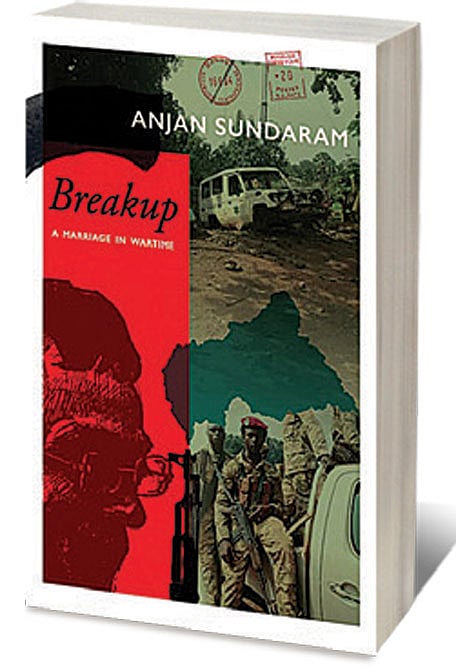

Lost in Battle

AUTHOR-JOURNALIST Anjan Sundaram revisits his marriage and ponders over the fragility of relationships in this slim memoir. In a tone replete with retrospective wisdom and melancholy, Breakup parses the memory of a marriage on its brink, attempting to make sense of its slow demise.

Juxtaposing his marital conflict with a real civil war, Sundaram, who reported from central Africa for The New York Times, Associated Press, and others, sets his memoir against the backdrop of tumultuous African geopolitics straddling the Central African Republic (CAR) and the tranquillity of Shippagan, a coastal town in Canada.

Bottled up in frosty remote Shippagan where he lived with his wife Nat and his infant daughter Raphaelle, Sundaram decides to pursue wartime reporting by setting out to travel deep into CAR where a civil war has been raging between destructive government forces and rebels.

As he ventures farther into CAR, losing connection with the outside world, a silent unrest brews in his personal life. In the absence of solid reasoning on why Sundaram’s marriage has been souring, it’s hard not to empathise with Nat, alone with a new-born whose anxieties now must include her husband’s whereabouts.

“I conjured up Nat’s face for comfort, but I knew I shouldn’t call her for reassurance,” writes Sundaram from the warfront. These cryptic deliverances add up to the confusion the reader feels over what really happened between the couple because the build-up to this stage of marital ruin is missing in the narrative. A little later when Sundaram calls home again, Nat is cold because the child’s feeding schedule has fallen on her. Put off by her reaction, Sundaram decides he won’t call her until he has news about his departure from CAR. Nat, perhaps unintentionally, emerges as a lonely figure grasping at the straws of maternal responsibility with an absent husband.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Meanwhile, near-death experiences follow Sundaram as he stumbles upon one war crime after another—massacres by government forces, burning of churches and schools, killing of a French photojournalist—and witnesses first-hand how civilians, like schoolteachers and priests, are forced to join the rebellion.

At one point when Sundaram’s team is held hostage at gunpoint by the rebel army, the presence of Lewis, an American companion who works for the Human Rights Watch, saves thousands of villagers seeking shelter in a church from an impending massacre. Faced with a bitter realisation that one American’s life is more precious than thousands of villagers in CAR, Sundaram tells Lewis, “You know how to stop all the wars in the world? Put an American with a satellite phone in every village, and if anyone threatens to attack, the US government will stop them.”

These sad racial realities of the world notwithstanding, when Sundaram describes his marriage, it becomes evident there’s palpable awkwardness in the relationship, not in the least due to lack of communication.

He examines the demise of his marriage impassively. “How much of my journey was about the war, and how much about my marriage? Could I tell Nat how close I had felt to her, even while we did not speak…? Or was it cloying, and making myself too vulnerable, to say how she and home and family gave me the courage to explore the limits of the war?”

Eventually as the simmering resentment boils over, one gets the sense of what pushed the marriage to the cliff’s edge. “You can make crazy journeys, while I’ve got to stay home,” Nat accuses him, asking, not unreasonably, “What kind of father risks his life?”

Unspoken in Sundaram’s own analysis is perhaps the residual trauma he may have suffered owing to his trip to CAR that resulted in exacerbating the marital crisis. “The end came after a period of estrangement and quiet torment, when neither of us felt loved. We lost our words. Something impassable had come up between us,” he writes.

Sundaram’s writing is incisive and brimming with a resolved sense of catharsis, yet there is no happy ending when a marriage breaks. What’s better than a stagnant marriage, if not a clean break and this book maturely documents it.