Jeet Thayil and Ranjit Hoskote on Indian Poetry

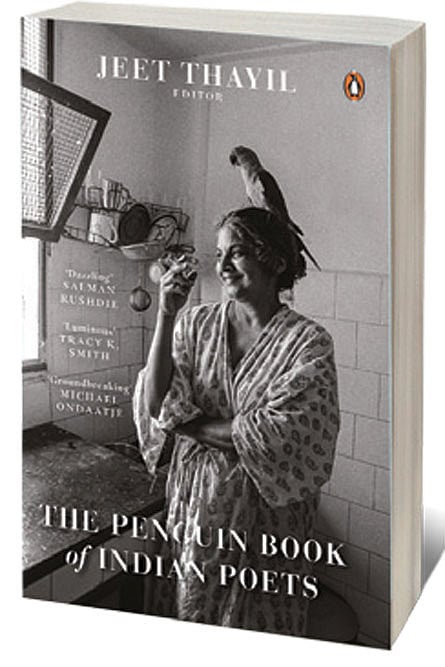

THE RECENTLY RELEASED The Penguin Book of Indian Poets edited by Jeet Thayil (Hamish Hamilton; 908 pages;₹ 1,499) is a mammoth book in terms of size and scope. Ninety-four poets can be found in this anthology, of whom 49 are women and 45 are men. The oldest poet in this collection was born in 1924, and the youngest was born in 2001. Poets Ranjit Hoskote (from Mumbai) and Jeet Thayil (from Bengaluru) got on a video call to speak about the making of anthologies and the importance of bringing back our forgotten poets. Excerpts from a conversation.

RANJIT HOSKOTE (RH): Jeet, it’s amazing to see the book in print, in this rather Biblical kind of avatar! Also, having been on this journey with you across all the iterations of the anthology, I’ve been struck by how it’s been a continuing commitment for you, apart from all your other practices as poet, novelist and musician. What drives you to work in the genre of the anthology?

Jeet Thayil (JT): This is the thing that started it in 2005 [holds up an issue of Fulcrum with poet Dom Moraes bent over a desk on the cover]. My friend Philip Nikolayev founded Fulcrum, a poetry annual out of Boston. Philip suggested, in 2003, that I edit an Indian supplement for the next issue, about 15 pages or so. But of course, once I started work, instead of a 15- or 20-page supplement, it became a 300-page anthology, and it swallowed that year’s Fulcrum. I returned to India in 2004 and since the book was not available here, I thought I should make an Indian version. The Fulcrum anthology had 52 poets. When I came to India and started thinking about it and expanding the idea a little, it became 60 Indian Poets [holds up 60 Indian Poets]. And then I thought, “OK, I should really offer it to a UK publisher.” I sent Neil Astley, editor of Bloodaxe Books, an email, and he said yes, enthusiastically. And then came this [holds up The Bloodaxe Book of Modern Indian Poets], which has 72 poets.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

And Ranjit, you are in all three of these volumes.

Then, in 2018, Meru Gokhale said, “Why don’t you update 60 Indian Poets?” I said yes, thinking it would take a month: I would carry out some quick refurbishment. But when I started work, the pandemic was upon us, and it seemed to me that 60 Indian Poets (2008) was outdated in every way. The theme of the three previous anthologies was craft. It was all about a formal engagement with the line, how it is both liberation and constriction.

But in 2018, it seemed absolutely irrelevant for that to be the overarching idea for an anthology. I wanted to widen the horizon. Of course, right from the first iteration there were poets from all over the world. But this time I expanded the remit so as not to be so concerned with the idea of craft, which is why The Penguin Book of Indian Poets (2022) is more political than the previous anthologies. It has more latitude in terms of inclusivity, and its criteria are different. There is an urgency and commitment in the voices of the poets in this book, and that is something you will discover even if you casually flip the pages. There’s something urgent being said, something personal, even something dangerous, uttered at some cost to the poet. So, for me, The Penguin Book of Indian Poets is the mother of them all, the final iteration of this twenty-year project.

RH: This might be a slightly polemical stance you’re taking, because each of the iterations was responsive to its own historical moment. I think it began with the need to map Anglophone poetry by Indians in a somewhat defensive way, which gave way to a much more confident stance. There always was your sense of wanting to include people of Indian heritage or some Indian connection, which made it a far more transcultural, more cosmopolitan kind of anthology, so it didn’t trap itself in only a nationalist debate.

You can think about various groupings of poets within the anthology, each of them inhabiting a different narrative, a different debate. Because there are people in the diaspora who are bringing in their own concerns about representation and identity politics.

Or there are poets who choose to live in India but are not necessarily troubled by questions of nationalism. I don’t think the craft question has gone away. You know this and you embody it in your own practice—you can’t really divorce questions of urgency from questions of craft.

So, you’re probably doing yourself an injustice, as I don’t think the earlier iterations were merely formalist. It’s just that the notion of urgency has grown far more intense now.

How do you account for the fact that, while all the contributors are united by their connection to India, they also inhabit different semantic and discursive contexts? They are really working out different kinds of destinies.

JT:A good moment to bring up Bruce King’s essay, ‘A Cultural Monument,’ which is placed at the exact centre of the book. The book starts with Nissim [Ezekiel]. The first half ends with AK Ramanujan. Then there’s Bruce, there’s Dom, and the second half ends with Arun [Kolatkar]. The reason Bruce’s essay occurs in the middle is because he places this book in a historical context, it’s a meta essay. It brings us to what you were talking about earlier, that the other books were also responses to their moments. It’s just that this one seems to cohere, for me at least, in a vital and defining way.

I’m very glad you asked this. The reason I didn’t order the poets chronologically by publication date or by date of birth, and so on, is because I wanted to bring out those hidden resonances that you will find between poets as far apart in terms of geographies and historical time as, for instance, Subhashini Kaligotla and Ramanujan.

Ramanujan is preceded by Subhashini and Arundhathi [Subramaniam] and you can see a through-line there. A poet like Sudesh Mishra who was born in Fiji, who lives there now, you read him, and you read the poets on either side of him, Vahni Capildeo and Sneha Subramanian Kanta, and all three cohere into a shared continuum. The only way to describe that continuum is to call it Indian poetry.

Sudesh is not even very familiar with India, as we know it. He knows it in the way [VS] Naipaul knew it, as a kind of a historical burden, really. But it’s so evident, this Indian burden.

And a poet like Pascale Petit [of French, Welsh and Indian heritage] who embodies the kind of transcultural identity I’m interested in. If you didn’t know her background and you were to read her as a poet based in Allahabad or Aurangabad or Alipore, it would work. There are no false notes, and for me, really, that was one of the most exciting parts of putting this together; making connections between poets who may not even know each other. It was entirely intuitive, sometimes counterintuitive, something that I lived with for a long time and thought about a lot, and kept adjusting until the book took the shape that it finally did.

RH: I like those intuitive connections very much. They do away with the notion of generations or other more conventional ways of forming these groupings. There’s a musical quality to it, a cadence, a sequence of motifs. All of that, for me, makes this anthology rich in its unpredictability.

JT: I love the idea of unpredictability. That’s the exact word.

RH: Also, there’s a kaleidoscopic sense of what it means to have any connection to India. When I did the first standalone Indian national pavilion at the Venice Biennale, in 2011, that was my theme—because, what do you do with a national pavilion at a major Biennale like that? You have to critique and question the idea of the nation-state. So, I chose four artists, who all questioned this simple idea of citizenship by birth or passport or residence. Each artist, to me, questioned what modern India might mean in its diverse plurality, its questions rather than its answers.

In this anthology I have that same sense, about each of the poets incarnating some larger disquiet. Not only is there a confidence in what you’re doing as a poet, but there’s also a sense of dealing with unstable identities, precarious conditions, and that this has to be renegotiated constantly.

This is very different from the anthologies that you and I grew up with, which now seem exceedingly stable even in their disquiet, with a kind of stylised anxiety. The previous anthologies all seemed like they came out of a particular club. Here, the impulse is different. It’s expansive, this anthology, it takes more risks. What is the connection between your choices as an anthologist and what you do as a poet? Because not all these poets share your poetics.

JT: In fact, some do just the opposite of what I might do.

For example, a poet like Raena Shirali, she’s described as avant-garde, so is Bhanu Kapil. But if you read those poems aloud, what you get is a sense of the human voice speaking very intimately, directly, to you, in charged, compressed, elevated language, and that’s what we want from poetry. We want a voice that will speak to us, in tough times, that we can return to, that will give us something to hold. Which is something I see as a running thread through this book. It was a criterion for me when choosing the poets—would they last ten years? Would they produce electric new work?

Take a poet like Hamraaz. We don’t know whether the poet is male or female, where they are based. We can make guesses. Hamraaz’s work is so specifically addressed to this particular Indian moment. Yet it has aspects that are timeless. I believe the poems will be relevant in ten years. When I look at the book and see the range of voices and of poetries, I know the collection will last.

RH: I completely agree.

I often think about this space between the book and the reader, which, in a visual arts context, Frank Stella used to call the “working space”. He meant the five feet that separate the viewer from the painting, where the work of interpretation really gets done. So, what might that be for you as an anthologist? What would your “working space” be, between a book and a reader?

JT: Did he say five feet?

I want five inches.

I want it in your face and impossible to ignore. I do believe that if you open this book at random, you will find a poem that grabs you by the lapels. The poems grab you and bring you close and say things you may not necessarily want to hear, but will leave you the richer for the hearing.

And also, I just want to add, one duty that has fallen upon me by accident, really, from the Fulcrum anthology to this one—was to bring back certain voices that have been excluded from the anthologies we were talking about earlier.

Now, when you think about it, it’s inexplicable. How do you leave out Lawrence Bantleman? How do you leave out Gopal Honnalgere? How do you leave out Srinivas Rayaprol? How do you leave out Kamala Das?

It’s inexplicable and the only way to understand it is as a club. These poets did not have the right shoes. They were not wearing the right type of trousers. That’s why they were left out. For me, from that first anthology, it was a duty to bring back our forgotten poets.

RH: That’s an important aspect of anthology-making. It shifts the emphasis to include something that’s very dear to me—what I think of as lost and found histories. How do you retrieve figures who were unjustly eclipsed or repressed from the record?

JT: I think it enriches an anthology, and ensures that it isn’t a priestly vocation, meant for a few already converted readers, but something in which anybody—even someone who may not necessarily call themselves a reader of poetry—can find something to enjoy or think about.

(As told to Nandini Nair)