‘If we give nature a chance, it can and will recover,’ says Beatrice Forshall

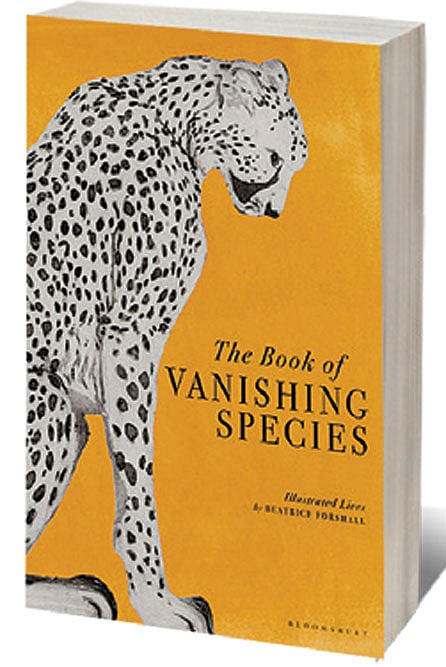

A FULL-TIME ARTIST and first-time author, Beatrice Forshall’s The Book of Vanishing Species (Bloomsbury; 256 pages; ₹2,299) combines science, biology and ecology with art. The result is a celebration of life on Earth and how “we are destroying it”. Through stories of 69 species, the book is a reminder of what we can learn from the extraordinary organisms inhabiting our natural environment and what we would lose without them. Though Forshall has no professional scientific background, it was during an artist’s residency with Cambridge Conservation Initiative (CCI) that she met leading biodiversity experts who inspired her to write this requiem. The 30-year-old speaks to Open from her home in Dartmoor, England about her lifelong love for nature, animals, and her views on the climate crisis. Excerpts:

The Book of Vanishing Species is a vivid showcase of your illustrations, but it’s also very much a primer on ecology and biology. What was the starting point for this book?

It’s something I’ve wanted to do since I was little. My mother is a painter and my father, a photographer. My sisters and I grew up around them working at home… in the kitchen, in the garden. My mother often cooks and paints at the same table. I spent my days outside in the fields around our house in France where I was born and I’ve always loved animals. I wanted to somehow bring these two sides of my life together. When I was young I hoped to work in wildlife conservation and when I was nine-years-old I started The Animal Club. Every other week a couple of friends and I would get together and make drawings and papier-mâché sculptures of endangered animals, which we would then sell at the local market to raise funds for the World Wildlife Fund, and I’ve never really stopped.

2026 Forecast

09 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 53

What to read and watch this year

I studied illustration at Falmouth College of Art in England. In every project, I would end up drawing threatened birds and in my final year I specialised in making engravings of them. In 2017, I was given an artist residency at the Cambridge Conservation Initiative (CCI), a collaboration between researchers, policymakers and practitioners from the University of Cambridge and biodiversity conservation organisations. There I met people who devote their careers to the conservation of particular species or habitat. I learned about the lives of some of the creatures with whom we share the planet and as I did so I wanted to tell their stories.

Art being your first love, tell us about the engravings in the book.

I make hand-painted drypoint engravings. I like the process and the textures one can create. It is labour intensive but each stage — the drawing, engraving, printing and then the painting — holds a different quality. So do the different materials — the metal, the paper, the ink. There is always an element of surprise at the end, which I love. The technique I use and the fact that the engravings are hand-coloured means that each final image varies slightly in form and colour and is therefore unique. For the book, I wrote the stories before I made the engravings. I wanted to learn all I could about the creatures before drawing them. I draw straight on to metal and then using a sharp tool, engrave into it. The large pieces can take weeks to engrave. I then ink the plate up and run paper and zinc through the press.

From mangroves and Brazil nut trees to plankton, dung beetles and vaquita, you cover a gamut of species that humanity is losing at an alarming rate.

The book includes 69 stories of different species, which are threatened, from tiny plankton to giant sequoias. I have divided it into four parts: Air, Water, Soil and Sapiens. I wanted to try and convey how connected life on Earth is, as are the systems, which support it. The book is about how species rely on one another and how we are destroying this delicate, intricate, generous web of life, which has taken millions of years to evolve. As we diminish this we make our beautiful planet less habitable. It is about the choices each of us make every day and the impact these have and how if allowed, nature can recover.

Do you have any favourite stories or pictures from the book?

I can’t pick any favourites but the first species I wrote about was the olm. It is an aquatic salamander that lives in caves in central and south-eastern Europe. It has no eyes but can sense light through its skin and has developed a heightened sense of taste and smell. It also hunts, navigates and avoids threats using electric and magnetic fields. It can live for a hundred years and go without food for up to ten. As a species it has been around 366 times longer than ours and survived whatever wiped out the dinosaurs. Yet because of us polluting and destroying its habitat, capturing it for the pet trade, it is now in decline. To me, this is a measure of the extent of our destructiveness. Another species with remarkable adaptations is the scaly-foot snail, whose exoskeleton is made of iron. It lives on the edge of hydrothermal vents in the Indian Ocean where the pressure is over one and a half times what it takes to crush a car for scrap. Many other species live in the deep ocean too — glass octopus, snailfish, bamboo coral, brittle stars… creatures we still know very little about but whose home is being destroyed by mining for metals and diamonds.

We are starting to see that many species demonstrate behaviour, which we once thought were uniquely human — to grieve, to love, show altruism, share culture. One of the stories included in The Book of Vanishing Species is that of the Asian elephant. Like orcas, whales, great apes and humans, their brains are equipped with spindle neurons, which play an important role in social interaction, intuition and emotion. When a member of their family dies they cover the body with branches and leaves. They are known to stroke and hold the bones of those deceased and to suffer post-traumatic stress in much the same way as we do. I find the way many of these creatures communicate and look after one another moving. They have strong bonds that last a lifetime. There is still so much we don’t know about their lives and I think they will always hold some mystery. Recently, I heard that orcas change the intensity of their song when they see the full moon or the Northern lights.

In the book you make a point that we know more about the moon’s surface than the sea floor. It seems like human activity is polluting oceans even without us knowing fully what lies beneath.

We have so much to learn about the oceans but what we do know is that their temperature is rising and as it does, their ability to absorb carbon is reduced, as is their regulation of the planet’s temperature. I love swimming in the sea. It is one of the things which make me feel most alive. Yet, swimming in clean waters is becoming harder. One of the things which saddens me is the thought that we are making the seas unbearable for their inhabitants. By polluting them but also by the industrial noises we make and which get trapped below their surface… propellers, underwater explosions, deep sea drilling, sonar. It is thought that this could be one of the causes of so many of the recent whale strandings. There is nowhere truly quiet for them to go.

You also write about the gharial and Asiatic cheetah, both native to India and among the most critically threatened creatures in the world.

On the front cover of The Book of Vanishing Species is an engraving I made of an Asiatic cheetah. They were once found in India but due to habitat loss and hunting for sport they were declared extinct there in 1952. There are just 12 Asiatic cheetahs alive in the wild today, all in Iran. It is thought that only two of them are female. Their existence holds on by a thread. It was important that the illustration on the front cover was that of the cheetah because if we can let such a majestic creature vanish, what hope is there for other species?

Like most reptiles, gharials have many offspring but unlike many, are devoted parents. It is not unusual to see scores of baby gharials being carried by a male on his back and the mothers taking turns to watch and care for their young. They are shy creatures and only feed on fish. They do not harm humans. Poaching, pollution and dams have greatly reduced their numbers. Chemicals and rising temperatures may be unbalancing their sex ratio. This species is now listed as critically endangered. Another Indian connection to the book are mangroves. They are places of exchange, where air, land, sea and fresh water mix, a habitat and food for many creatures. They are one of the planet’s most important ecosystems and India and Bangladesh are home to one of the biggest mangrove forests in the world — the Sundarbans. These forests, so full of life, are being replaced by coastal development, rising sea levels and fish farms.

When did you become conscious of nature as an all-nourishing force?

I grew up in a rural part of France and as a child I spent my days in the fields and woods around our house. If you spend time in something which is so magical you can’t help but love it and want to care for it.

You wrote the book during the pandemic. Did you see nature around you blooming once again?

I was in France working on this book and felt very fortunate to be in the countryside. For the first time since I was little I heard the call of the turtle dove. They are shot along their migration route and are becoming rarer but in 2019 we heard them throughout the spring and this gave me hope. For weeks there were no planes flying above the house and it was very peaceful. If we give it the chance, nature can and will recover.

How do you feel about climate change and what kind of impact will it have on the future generation?

Like many people I find it very worrying. The effects of climate change are appearing all around us and often most noticeably in countries which are least responsible. The consequences of inaction will be so severe, that to have any chance of a habitable planet we have to act now. Climate change and biodiversity loss is the greatest challenge we’ve ever had to face and it’s very easy to feel overwhelmed by it and to think that our individual actions don’t make a difference. I believe they do and that the way to overcome eco-anxiety is to act. I find it exciting that as an individual the choices I make every day — what I buy, eat, how I travel — matters.